Flashback 2007 & 2014: "As things change in the future, who decides how the gains & losses are shared between developer profit & housing affordability?"

Some Atlantic Yards observations remain evergreen.

On July 1, 2007, after the New York Times published Official Sees Possible Risk in Big Project in Brooklyn, a murky but prescient article about documents revealed to Assemblymember Jim Brennan, I contacted David A. Smith, an affordable housing analyst in Boston who'd previously reviewed Atlantic Yards documents.

His observations, in italics below, were prescient.

They were again prescient when I quoted them in 2014 after the new deal establishing a May 31, 2025 deadline for 2,250 units of affordable housing, which won't be met, with the future murky.

His observations remain prescient, as a renegotiation looms. I've interpolated some comments.

"Extraordinarily complex"

Even a cursory review of the financing plan materials released so far reveals that this is an extraordinarily complex undertaking, with many moving parts. The moving parts -- the financing plan, with multiple phases, multiple property uses, and multiple potential sources including subsidy and concessionary government capital -- mean volatility.

There were--and would be--even more moving parts, of course, including a new developer, and new cycles of politics, economics, and tax breaks/subsidies.Sequencing is key

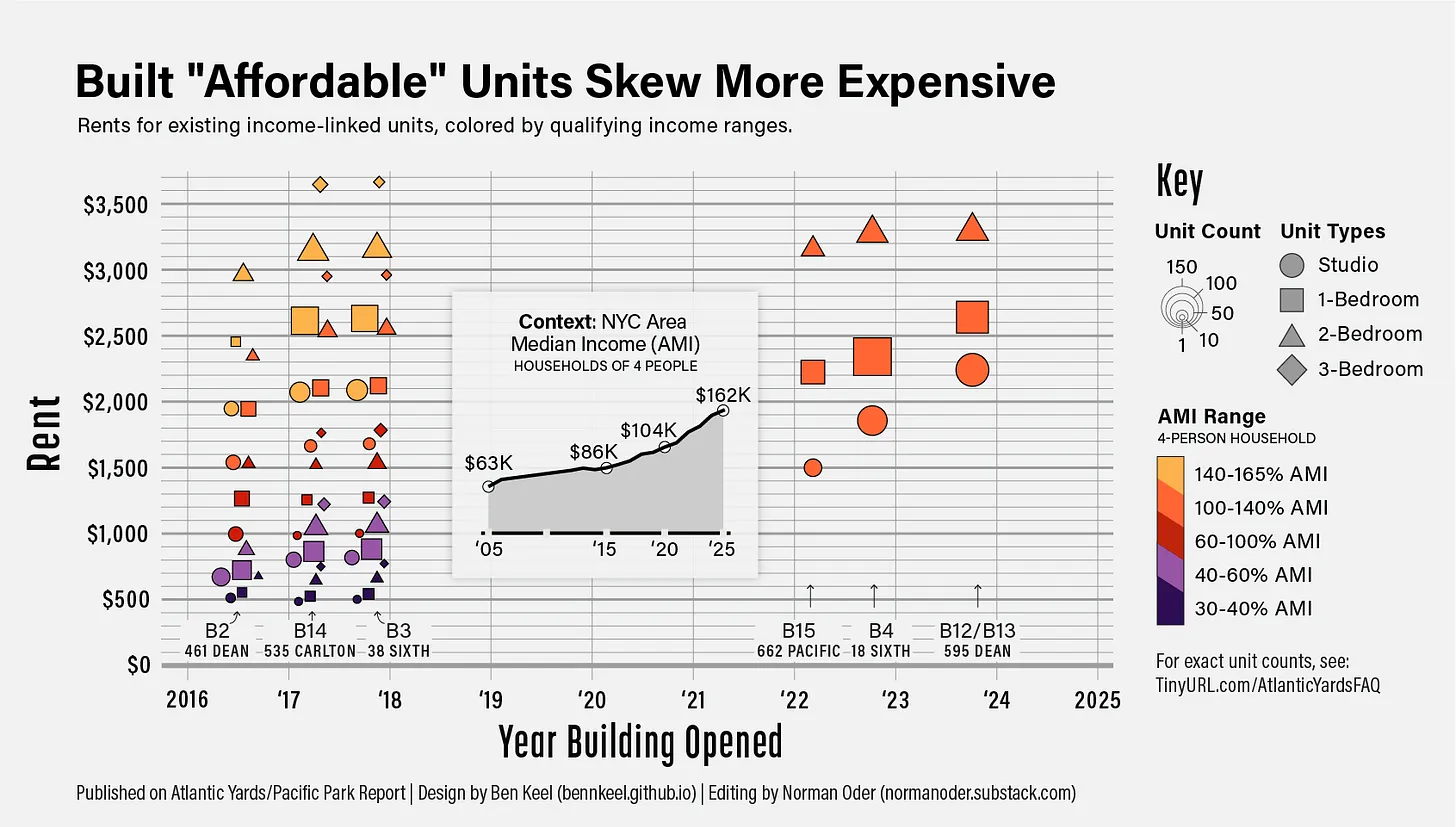

It could be a great financial and economic result, or a terrible one. With this much volatility, sequencing is key: what happens in what order, and who decides what changes are made to the development plan? If the developer has all the optionality -- that is, control over the responsive actions taken after unexpected favorable or unfavorable outside events -- and the city has none of the optionality, then it's very likely that the developer can navigate through all the complexity to a successful deal, and achieve this result by adjusting the affordable housing to be fewer apartments, to happen later in the development sequence, and to be redefined upwards. (Anyone who does business with any government agency as a counterparty knows that managing expectations over time is a critical developer skill.)

The developer doesn't have "all the optionality," but has generally been given a long leash. Consider that a project expected to take ten years was allowed to take 25 years, until 2035 but then, in 2014, the affordable housing was assigned the 2025 deadline.

The question isn't, "Could the developer make a lot of money?" nor even "What is the public getting and what is the public paying?" but rather, "As things change in the future, who decides how the gains and losses are shared between developer profit and housing affordability?"

I have been with developers who have suggested that working with the city can cost $1 million or more in the lost time value of money, but when they look at the product of a critical public process, they will admit to seeing this paper loss evaporated by dramatically improving the public trust. The public’s trust is the capital developers need most in a democratic society. The main question therefore becomes who are the brokers of this trust (freely given for the most part) in the Atlantic Yards and Columbia proposals? If these brokers betray people who simply demand effective inclusion, will they betray us all? This is the essential political point.(Emphasis in original)

Comments

Post a Comment