In an emphatic yet potentially questionable decision, U.S. District Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis yesterday dismissed Goldstein v. Pataki, the federal lawsuit challenging eminent domain that Atlantic Yards opponents have considered their best hope for stopping the project.

In his decision, Garaufis ruled that even if public benefits—including new tax revenues, housing, jobs, and the elimination of blight—are less than promised, they’re sufficient to overcome allegations that the project is a sweetheart deal benefiting developer Forest City Ratner.

“Because Plaintiffs concede that the Project will create large quantities of housing and office space, as well as a sports arena, in an area that is mostly blighted, Plaintiffs’ allegations, if proven, would not permit a reasonable juror to conclude that the 'sole purpose' of the Project is to confer a private benefit,” Garaufis wrote. “Neither would those allegations permit a reasonable juror to conclude that the purposes offered in support of the Project are 'mere pretexts' for an actual purpose to confer a private benefit on FCRC.”

Despite the setback, the plaintiffs, 13 owners and renters whose properties lie in the southern segment of the 22-acre footprint, outside the longstanding Atlantic Terminal Renewal Area (ATURA) that encompasses the Vanderbilt Yard, vowed to appeal.

Appeal issues

“We have a nice issue for an appellate court to decide,” said plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff. “Undisputed facts lead to an inference that this was driven for Ratner’s benefit. It’s undisputed that no other developer was considered to do this project, that the genesis was Forest City Ratner, that they identified my clients’ properties [for eminent domain], and that the government, broadly speaking, agreed to do exactly what [the developer] asked for. If those facts don’t give rise to a claim under the public use clause, it’s definitely a dead letter, for anybody.”

Beyond that, unmentioned by Brinckerhoff, the judge apparently misread the plaintiffs’ position on blight. “Plaintiffs assert either that the Takings Area is not blighted or that whatever blight may exist was caused by FCRC,” Garaufis wrote. “But Plaintiffs do not dispute that the majority of the Project Area–which encompasses the Takings Area – is blighted, and in fact they seem to concede that it is.”

Beyond that, unmentioned by Brinckerhoff, the judge apparently misread the plaintiffs’ position on blight. “Plaintiffs assert either that the Takings Area is not blighted or that whatever blight may exist was caused by FCRC,” Garaufis wrote. “But Plaintiffs do not dispute that the majority of the Project Area–which encompasses the Takings Area – is blighted, and in fact they seem to concede that it is.”

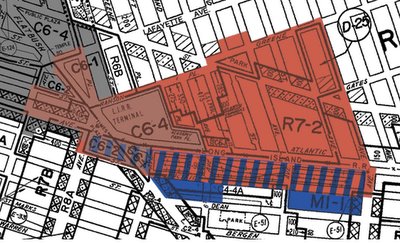

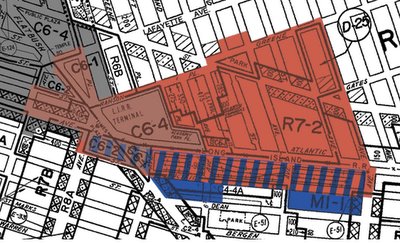

[More than half of the Atlantic Yards footprint, including the railyard, would fall within the boundaries of ATURA. In the map above, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Actually, the plaintiffs challenged the analysis in the Blight Study: “Even accepting the six characteristics of blight described by [consultant] AKRF for each lot in the Blight Study, only 27% of the 73 parcels examined, at most, could be considered blighted," they said in the amended complaint. (That doesn't fully compute, since AKRF asserts a large majority of parcels blighted. Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn's blight response challenges AKRF's analysis by questioning the application of the blight characteristics.)

Indeed, DDDB which organized the case and whose spokesman Daniel Goldstein is the lead plaintiff, has also questioned the Blight Study as part of a pending state lawsuit challenging the Atlantic Yards environmental review.

In the federal lawsuit, the plaintiffs pointed to the “Takings Area,” the blocks on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean, near where new construction proliferates. “Indeed, far from being ‘blighted,’ the Takings Area rests smack in the middle of some of the most valuable real estate in Brooklyn.” (The site as a whole was described in March by Chuck Ratner, an executive with the developer's parent company Forest City Enterprises, as “a great piece of real estate.”)

Garaufis also described the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) “Vanderbilt Rail Yard” as “ dormant part of the blighted ATURA area,” which isn’t accurate, given that it was and remains a working railyard.

Defendants comment

The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) , the main defendant along with the developer and city and state officials, issued a statement: "We are pleased by the decision, which reaffirms the Atlantic Yards project's many public benefits: affordable housing, a world-class sports venue, improved transportation and increased economic activity. This is yet another instance in which the project has stood up to legal scrutiny, and we remain confident that the project will continue to prevail in the courts."

Forest City Ratner CEO Bruce Ratner said in a statement, "This decision means we are one step closer to creating over 2,200 units of affordable housing, thousands of construction and office jobs and bringing the Nets to Brooklyn."

(The developer faces many other hurdles, including the scarcity, at least for now, of tax-exempt bond financing for the housing.)

Winding road

The plaintiffs based their case, filed in October, on the evolving notion of public purpose, drawing on the Supreme Court’s 2005 5-4 Kelo v. New London decision, which upheld the city’s use of eminent domain for economic development, but noted that the taking came out of a carefully considered development plan.

Beyond that, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote a concurrence in which he observed that a “court confronted with a plausible accusation of impermissible favoritism to private parties should treat the objection as a serious one and review the record to see if it has merit, though with the presumption that the government’s actions were reasonable and intended to serve a public purpose.”

The Brooklyn case has been the subject of a significant volley of legal briefs and two lengthy and contentious oral arguments. The initial argument was held February 7 before U.S. Magistrate Judge Robert M. Levy, to whom Garaufis referred the defendants’ motions to dismiss the case.

While Levy seemed fascinated by the question of when the balance of public and private purposes behind a project is so wrong that a court must intervene, on February 23 he dismissed the case on procedural grounds, citing a case called Burford, rather than addressing the merits of the case, assessing whether the plaintiffs had stated a claim sufficient to go forward.

Levy's ruling would've sent the plaintiffs to state court, but they'd vastly prefer to stay in federal court, where they’d have more power to extract information from the defendants via discovery. They appealed Levy’s recommendation to Garaufis, who held his hearing on March 30.

Overturning Burford

In the hearing, Garaufis seemed receptive to the plaintiffs’ challenge to Levy’s Burford decision and, indeed, yesterday he overturned it. “The court declines to abstain under Burford,” he wrote. “Such abstention would be inappropriate because federal-court review of the questions presented in this and similar cases will not disrupt New York’s effort to establish a coherent eminent-domain policy.”

In doing so, Garaufis rejected arguments that the state’s Eminent Domain Procedure Law sets out the exclusive policy for considering eminent domain challenges. “This court must abstain only if 'exercis[ing] of federal review of the question in [this] case and in similar cases would be disruptive of state efforts to establish a coherent policy with respect to a matter of substantial public concern,'” Garaufis wrote, citing a previous case.

“My concern, therefore, is with the EDPL’s coherence, not with any of its other virtues, such as reducing litigation and promoting efficiency.” Scoffing at an ESDC argument, he wrote, “The court is not aware of any danger of 'piecemeal adjudication' that may result if the court hears this case.

Hinting at the boundaries

In his 66-page opinion, Garaufis devoted the single largest segment, 31 pages, to Burford, as if enjoying the legal workout of a complicated jurisdictional issue. In chiding the defendants in that section, he offered a strong hint of the ruling to come several pages later.

He wrote, “But this court is not being asked to evaluate the political questions underlying the Project. This case simply does not require the court to consider whether the Project is a good idea or whether it can be achieved only by taking Plaintiffs’ properties as opposed to other properties or no private properties at all. Instead, the issue before this court is whether the taking of Plaintiffs’ properties is rationally related to a conceivable public use, as required by the United States Constitution... This is a question of federal law, not local policy, and I am obligated to address it.”

Staying in federal court

Levy also had recommended rejection of two other grounds for dismissal posited by the defense, one based on a case called Younger and the other because the case was allegedly not yet ripe for review. Garaufis upheld those recommendations.

Thus the plaintiffs achieved one of their goals, convincing a judge that their case belonged in federal rather than state court. That procedural but hardly ultimate victory got prominence in DDDB’s press release, which secondarily acknowledged the judge’s ruling that the complaint was insufficient.

"We will continue to pursue every single legal option available to the plaintiffs, wherever they lead us, to stop what we believe is a private taking in violation of the U.S. Constitution," said DDDB legal team coordinator Candace Carponter.

Public use

In a coda to his 2/23/07 ruling , Levy wrote, "Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint raises serious and difficult questions regarding the exercise of eminent domain under emerging Supreme Court jurisprudence, many of which were explored in some detail at oral argument. However, in light of my recommendation that this court abstain, it would be inappropriate to address plaintiffs’ claims on the merits."

Garaufis may have considered the questions serious, but his opinion suggests he did not find them difficult.

In addressing the issue of eminent domain for public use—which today means “public purpose” rather than such clear public uses as parks or highways—Garaufis discussed not only Kelo but two seminal predecessor cases, the Washington, DC case Berman v. Parker (1954) and the follow-up Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff (1984).

In Midkiff, he noted, the court cited Berman, in saying that the judiciary has an “extremely narrow” role “in reviewing a legislature’s judgment as to what constitutes a public use.” And the Supreme Court set out a standard: “When the legislature’s purpose is legitimate and its means are not irrational, [Supreme Court] cases make clear that empirical debates over the wisdom of takings–no less than debates over the wisdom of other kinds of socioeconomic legislation–are not to be carried out in the federal courts.”

Kelo standard?

In Kennedy's Kelo concurrence, Garaufis noted, the justice acknowledged that there may be eminent domain cases that demand stricter scrutiny, but that Kelo wasn’t that case because “(1) the Kelo taking 'occurred in the context of a comprehensive development plan meant to address a serious city-wide depression,' (2) 'the projected economic benefits of the project cannot be characterized as de minimis,' (3) '[t]he identity of most of the private beneficiaries [of the Kelo project] were unknown at the time the city formulated its plans,' and (4) '[t]he city complied with elaborate procedural requirements that facilitate review of the record and inquiry into the city’s purposes.'”

Oddly enough, after citing Kennedy’s standard, Garaufis did not grapple with it. Earlier in his ruling, he offered a factual description of the case. He noted that the MTA had before September 2003 said—according to the plaintiffs—that it had sold Forest City Ratner rights to the Vanderbilt Yard, then later retracted it. Also, he noted that, on 5/25/05, the MTA issued a request for proposals for the railyard. As plaintiffs have noted, that was some 18 months after the project was announced, a sign of favoritism.

Garaufis, however, didn’t examine whether that sequence “occurred in the context of a comprehensive development plan” or whether the private beneficiaries were unknown, as stated by Kennedy. Nor did he address whether the ESDC, whose board is appointed by the governor, constitutes a legislative agency, as seemingly required.

Rather, Garaufis focused on the clear language in the Supreme Court opinions in Kelo and Midkiff, which stated that a “taking fails the public use requirement” only if the “uses offered to justify it are ‘palpably without reasonable foundation,’” if the “sole purpose” is to transfer property to a private party, and if the announced purpose is a “mere pretext” for a private benefit.

Those standards were not met by the plaintiffs. Garaufis pointed to claims that Atlantic Yards will generate no or minimal economic benefits, will not create jobs, and will not materially increase affordable housing. Moreover, he noted, plaintiffs claim the area is not blighted.

Degree of benefit, not absence

“That conclusion is baseless and may be rejected even at this early stage of the litigation,” Garaufis wrote. “Each of the four allegations just listed, when examined carefully, concerns only the measure of a public benefit – as opposed to its existence – or otherwise fails to state a claim.” He pointed out that plaintiffs conceded some public benefit--though, as noted above, he may have misread the plaintiffs’ “concession” regarding blight.

Even if the plaintiffs’ own properties are not blighted, non-blighted properties may be subject to eminent domain, according to Berman, “if the redevelopment is intended to cure and prevent reversion to blight in some larger area that includes the property,” Garaufis wrote. The plaintiffs, however, argue that the map was drawn by the developer, so the question may be just how much could be added to an area deemed blighted.

Political judgment?

What if Atlantic Yards doesn't fulfill the goals regarding housing and jobs? Garaufis noted that it wasn’t the court’s role to examine whether the project will achieve the objectives stated, citing language in Kelo that notes that such a requirement “would unquestionably impose a significant impediment to the successful consummation of many such plans.”

Also, citing the plaintiffs’ criticism of the affordable housing planned, Garaufis wrote, “Whether these units are sufficiently affordable may be an important political question, and if the citizens of Brooklyn are unsatisfied with the answers, then elected officials and their political parties may pay the price at the polls. But the Constitution does not enshrine Plaintiffs’ value judgment that a taking lacks a public purpose if it results in ‘luxury’ as opposed to ‘affordable’ housing, and the constitutionality of this taking does not depend on the relative numbers of planned housing units priced at, above, or below market rate.”

That statement echoes one made in the February oral argument by ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus, who said of Brinckerhoff, “If his clients or if other members of the community think this was really a terrible project, they can express themselves in the next election when they vote for their City Council representatives, their State Senators, their State Assembly members, their Congresspersons, and their federal Senators."

However, none of those officials actually had jurisdiction over Atlantic Yards, which went from the ESDC to the Public Authorities Control Board, whose votes last December were controlled by then-Governor George Pataki, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno.

In March, affordable housing analyst David Smith commented on Kraus’s statement, “[I]f the project is terrible, and the sole remedy is electoral relief, then there is no check in law to a development agency run amok.”

What’s a pretext?

During the March eminent domain hearing, ESDC lawyer Kraus set out a formulation that apparently the judge found convincing. “The plaintiffs don’t say there won’t be jobs here,” he said. “You have to say that there’s no proper public purpose or that if there is one, the project has no conceivable relationship.”

Garaufis acknowledged that the Second Circuit, the appellate court he looks to for initial guidance, “has not yet had the opportunity to articulate the standard according to which this court should measure whether an asserted use is merely pretextual.”

He went on to examine Kennedy’s concurrence. He wrote, “Justice Kennedy therefore instructed that ‘[a] court confronted with a plausible accusation of impermissible favoritism to private parties should treat the objection as a serious one and review the record to see if it has merit, though with the presumption that the government’s actions were reasonable and intended to serve a public purpose.’”

That, Garaufis wrote, the plaintiffs have not done. They may be alleging “that the purported purposes of the Project are dubious,” but Kelo requires an allegation that the “actual purpose” is “to bestow a private benefit” on the developer, he wrote.

“Therefore, even if Plaintiffs could prove every allegation in the Amended Complaint, a reasonable juror would not be able to conclude that the public purposes offered in support of the Project are ‘mere pretexts’ within the meaning of Kelo, i.e., mere pretexts for an actual purpose to bestow a private benefit,” he concluded.

That emphatic ruling may be in tension with both Kennedy’s concurrence and the sequencing alleged by the plaintiffs. The resolution will emerge in the appeal, which could take four to six months.

In his decision, Garaufis ruled that even if public benefits—including new tax revenues, housing, jobs, and the elimination of blight—are less than promised, they’re sufficient to overcome allegations that the project is a sweetheart deal benefiting developer Forest City Ratner.

“Because Plaintiffs concede that the Project will create large quantities of housing and office space, as well as a sports arena, in an area that is mostly blighted, Plaintiffs’ allegations, if proven, would not permit a reasonable juror to conclude that the 'sole purpose' of the Project is to confer a private benefit,” Garaufis wrote. “Neither would those allegations permit a reasonable juror to conclude that the purposes offered in support of the Project are 'mere pretexts' for an actual purpose to confer a private benefit on FCRC.”

Despite the setback, the plaintiffs, 13 owners and renters whose properties lie in the southern segment of the 22-acre footprint, outside the longstanding Atlantic Terminal Renewal Area (ATURA) that encompasses the Vanderbilt Yard, vowed to appeal.

Appeal issues

“We have a nice issue for an appellate court to decide,” said plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff. “Undisputed facts lead to an inference that this was driven for Ratner’s benefit. It’s undisputed that no other developer was considered to do this project, that the genesis was Forest City Ratner, that they identified my clients’ properties [for eminent domain], and that the government, broadly speaking, agreed to do exactly what [the developer] asked for. If those facts don’t give rise to a claim under the public use clause, it’s definitely a dead letter, for anybody.”

Beyond that, unmentioned by Brinckerhoff, the judge apparently misread the plaintiffs’ position on blight. “Plaintiffs assert either that the Takings Area is not blighted or that whatever blight may exist was caused by FCRC,” Garaufis wrote. “But Plaintiffs do not dispute that the majority of the Project Area–which encompasses the Takings Area – is blighted, and in fact they seem to concede that it is.”

Beyond that, unmentioned by Brinckerhoff, the judge apparently misread the plaintiffs’ position on blight. “Plaintiffs assert either that the Takings Area is not blighted or that whatever blight may exist was caused by FCRC,” Garaufis wrote. “But Plaintiffs do not dispute that the majority of the Project Area–which encompasses the Takings Area – is blighted, and in fact they seem to concede that it is.”[More than half of the Atlantic Yards footprint, including the railyard, would fall within the boundaries of ATURA. In the map above, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Actually, the plaintiffs challenged the analysis in the Blight Study: “Even accepting the six characteristics of blight described by [consultant] AKRF for each lot in the Blight Study, only 27% of the 73 parcels examined, at most, could be considered blighted," they said in the amended complaint. (That doesn't fully compute, since AKRF asserts a large majority of parcels blighted. Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn's blight response challenges AKRF's analysis by questioning the application of the blight characteristics.)

Indeed, DDDB which organized the case and whose spokesman Daniel Goldstein is the lead plaintiff, has also questioned the Blight Study as part of a pending state lawsuit challenging the Atlantic Yards environmental review.

In the federal lawsuit, the plaintiffs pointed to the “Takings Area,” the blocks on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean, near where new construction proliferates. “Indeed, far from being ‘blighted,’ the Takings Area rests smack in the middle of some of the most valuable real estate in Brooklyn.” (The site as a whole was described in March by Chuck Ratner, an executive with the developer's parent company Forest City Enterprises, as “a great piece of real estate.”)

Garaufis also described the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) “Vanderbilt Rail Yard” as “ dormant part of the blighted ATURA area,” which isn’t accurate, given that it was and remains a working railyard.

Defendants comment

The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) , the main defendant along with the developer and city and state officials, issued a statement: "We are pleased by the decision, which reaffirms the Atlantic Yards project's many public benefits: affordable housing, a world-class sports venue, improved transportation and increased economic activity. This is yet another instance in which the project has stood up to legal scrutiny, and we remain confident that the project will continue to prevail in the courts."

Forest City Ratner CEO Bruce Ratner said in a statement, "This decision means we are one step closer to creating over 2,200 units of affordable housing, thousands of construction and office jobs and bringing the Nets to Brooklyn."

(The developer faces many other hurdles, including the scarcity, at least for now, of tax-exempt bond financing for the housing.)

Winding road

The plaintiffs based their case, filed in October, on the evolving notion of public purpose, drawing on the Supreme Court’s 2005 5-4 Kelo v. New London decision, which upheld the city’s use of eminent domain for economic development, but noted that the taking came out of a carefully considered development plan.

Beyond that, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote a concurrence in which he observed that a “court confronted with a plausible accusation of impermissible favoritism to private parties should treat the objection as a serious one and review the record to see if it has merit, though with the presumption that the government’s actions were reasonable and intended to serve a public purpose.”

The Brooklyn case has been the subject of a significant volley of legal briefs and two lengthy and contentious oral arguments. The initial argument was held February 7 before U.S. Magistrate Judge Robert M. Levy, to whom Garaufis referred the defendants’ motions to dismiss the case.

While Levy seemed fascinated by the question of when the balance of public and private purposes behind a project is so wrong that a court must intervene, on February 23 he dismissed the case on procedural grounds, citing a case called Burford, rather than addressing the merits of the case, assessing whether the plaintiffs had stated a claim sufficient to go forward.

Levy's ruling would've sent the plaintiffs to state court, but they'd vastly prefer to stay in federal court, where they’d have more power to extract information from the defendants via discovery. They appealed Levy’s recommendation to Garaufis, who held his hearing on March 30.

Overturning Burford

In the hearing, Garaufis seemed receptive to the plaintiffs’ challenge to Levy’s Burford decision and, indeed, yesterday he overturned it. “The court declines to abstain under Burford,” he wrote. “Such abstention would be inappropriate because federal-court review of the questions presented in this and similar cases will not disrupt New York’s effort to establish a coherent eminent-domain policy.”

In doing so, Garaufis rejected arguments that the state’s Eminent Domain Procedure Law sets out the exclusive policy for considering eminent domain challenges. “This court must abstain only if 'exercis[ing] of federal review of the question in [this] case and in similar cases would be disruptive of state efforts to establish a coherent policy with respect to a matter of substantial public concern,'” Garaufis wrote, citing a previous case.

“My concern, therefore, is with the EDPL’s coherence, not with any of its other virtues, such as reducing litigation and promoting efficiency.” Scoffing at an ESDC argument, he wrote, “The court is not aware of any danger of 'piecemeal adjudication' that may result if the court hears this case.

Hinting at the boundaries

In his 66-page opinion, Garaufis devoted the single largest segment, 31 pages, to Burford, as if enjoying the legal workout of a complicated jurisdictional issue. In chiding the defendants in that section, he offered a strong hint of the ruling to come several pages later.

He wrote, “But this court is not being asked to evaluate the political questions underlying the Project. This case simply does not require the court to consider whether the Project is a good idea or whether it can be achieved only by taking Plaintiffs’ properties as opposed to other properties or no private properties at all. Instead, the issue before this court is whether the taking of Plaintiffs’ properties is rationally related to a conceivable public use, as required by the United States Constitution... This is a question of federal law, not local policy, and I am obligated to address it.”

Staying in federal court

Levy also had recommended rejection of two other grounds for dismissal posited by the defense, one based on a case called Younger and the other because the case was allegedly not yet ripe for review. Garaufis upheld those recommendations.

Thus the plaintiffs achieved one of their goals, convincing a judge that their case belonged in federal rather than state court. That procedural but hardly ultimate victory got prominence in DDDB’s press release, which secondarily acknowledged the judge’s ruling that the complaint was insufficient.

"We will continue to pursue every single legal option available to the plaintiffs, wherever they lead us, to stop what we believe is a private taking in violation of the U.S. Constitution," said DDDB legal team coordinator Candace Carponter.

Public use

In a coda to his 2/23/07 ruling , Levy wrote, "Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint raises serious and difficult questions regarding the exercise of eminent domain under emerging Supreme Court jurisprudence, many of which were explored in some detail at oral argument. However, in light of my recommendation that this court abstain, it would be inappropriate to address plaintiffs’ claims on the merits."

Garaufis may have considered the questions serious, but his opinion suggests he did not find them difficult.

In addressing the issue of eminent domain for public use—which today means “public purpose” rather than such clear public uses as parks or highways—Garaufis discussed not only Kelo but two seminal predecessor cases, the Washington, DC case Berman v. Parker (1954) and the follow-up Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff (1984).

In Midkiff, he noted, the court cited Berman, in saying that the judiciary has an “extremely narrow” role “in reviewing a legislature’s judgment as to what constitutes a public use.” And the Supreme Court set out a standard: “When the legislature’s purpose is legitimate and its means are not irrational, [Supreme Court] cases make clear that empirical debates over the wisdom of takings–no less than debates over the wisdom of other kinds of socioeconomic legislation–are not to be carried out in the federal courts.”

Kelo standard?

In Kennedy's Kelo concurrence, Garaufis noted, the justice acknowledged that there may be eminent domain cases that demand stricter scrutiny, but that Kelo wasn’t that case because “(1) the Kelo taking 'occurred in the context of a comprehensive development plan meant to address a serious city-wide depression,' (2) 'the projected economic benefits of the project cannot be characterized as de minimis,' (3) '[t]he identity of most of the private beneficiaries [of the Kelo project] were unknown at the time the city formulated its plans,' and (4) '[t]he city complied with elaborate procedural requirements that facilitate review of the record and inquiry into the city’s purposes.'”

Oddly enough, after citing Kennedy’s standard, Garaufis did not grapple with it. Earlier in his ruling, he offered a factual description of the case. He noted that the MTA had before September 2003 said—according to the plaintiffs—that it had sold Forest City Ratner rights to the Vanderbilt Yard, then later retracted it. Also, he noted that, on 5/25/05, the MTA issued a request for proposals for the railyard. As plaintiffs have noted, that was some 18 months after the project was announced, a sign of favoritism.

Garaufis, however, didn’t examine whether that sequence “occurred in the context of a comprehensive development plan” or whether the private beneficiaries were unknown, as stated by Kennedy. Nor did he address whether the ESDC, whose board is appointed by the governor, constitutes a legislative agency, as seemingly required.

Rather, Garaufis focused on the clear language in the Supreme Court opinions in Kelo and Midkiff, which stated that a “taking fails the public use requirement” only if the “uses offered to justify it are ‘palpably without reasonable foundation,’” if the “sole purpose” is to transfer property to a private party, and if the announced purpose is a “mere pretext” for a private benefit.

Those standards were not met by the plaintiffs. Garaufis pointed to claims that Atlantic Yards will generate no or minimal economic benefits, will not create jobs, and will not materially increase affordable housing. Moreover, he noted, plaintiffs claim the area is not blighted.

Degree of benefit, not absence

“That conclusion is baseless and may be rejected even at this early stage of the litigation,” Garaufis wrote. “Each of the four allegations just listed, when examined carefully, concerns only the measure of a public benefit – as opposed to its existence – or otherwise fails to state a claim.” He pointed out that plaintiffs conceded some public benefit--though, as noted above, he may have misread the plaintiffs’ “concession” regarding blight.

Even if the plaintiffs’ own properties are not blighted, non-blighted properties may be subject to eminent domain, according to Berman, “if the redevelopment is intended to cure and prevent reversion to blight in some larger area that includes the property,” Garaufis wrote. The plaintiffs, however, argue that the map was drawn by the developer, so the question may be just how much could be added to an area deemed blighted.

Political judgment?

What if Atlantic Yards doesn't fulfill the goals regarding housing and jobs? Garaufis noted that it wasn’t the court’s role to examine whether the project will achieve the objectives stated, citing language in Kelo that notes that such a requirement “would unquestionably impose a significant impediment to the successful consummation of many such plans.”

Also, citing the plaintiffs’ criticism of the affordable housing planned, Garaufis wrote, “Whether these units are sufficiently affordable may be an important political question, and if the citizens of Brooklyn are unsatisfied with the answers, then elected officials and their political parties may pay the price at the polls. But the Constitution does not enshrine Plaintiffs’ value judgment that a taking lacks a public purpose if it results in ‘luxury’ as opposed to ‘affordable’ housing, and the constitutionality of this taking does not depend on the relative numbers of planned housing units priced at, above, or below market rate.”

That statement echoes one made in the February oral argument by ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus, who said of Brinckerhoff, “If his clients or if other members of the community think this was really a terrible project, they can express themselves in the next election when they vote for their City Council representatives, their State Senators, their State Assembly members, their Congresspersons, and their federal Senators."

However, none of those officials actually had jurisdiction over Atlantic Yards, which went from the ESDC to the Public Authorities Control Board, whose votes last December were controlled by then-Governor George Pataki, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno.

In March, affordable housing analyst David Smith commented on Kraus’s statement, “[I]f the project is terrible, and the sole remedy is electoral relief, then there is no check in law to a development agency run amok.”

What’s a pretext?

During the March eminent domain hearing, ESDC lawyer Kraus set out a formulation that apparently the judge found convincing. “The plaintiffs don’t say there won’t be jobs here,” he said. “You have to say that there’s no proper public purpose or that if there is one, the project has no conceivable relationship.”

Garaufis acknowledged that the Second Circuit, the appellate court he looks to for initial guidance, “has not yet had the opportunity to articulate the standard according to which this court should measure whether an asserted use is merely pretextual.”

He went on to examine Kennedy’s concurrence. He wrote, “Justice Kennedy therefore instructed that ‘[a] court confronted with a plausible accusation of impermissible favoritism to private parties should treat the objection as a serious one and review the record to see if it has merit, though with the presumption that the government’s actions were reasonable and intended to serve a public purpose.’”

That, Garaufis wrote, the plaintiffs have not done. They may be alleging “that the purported purposes of the Project are dubious,” but Kelo requires an allegation that the “actual purpose” is “to bestow a private benefit” on the developer, he wrote.

“Therefore, even if Plaintiffs could prove every allegation in the Amended Complaint, a reasonable juror would not be able to conclude that the public purposes offered in support of the Project are ‘mere pretexts’ within the meaning of Kelo, i.e., mere pretexts for an actual purpose to bestow a private benefit,” he concluded.

That emphatic ruling may be in tension with both Kennedy’s concurrence and the sequencing alleged by the plaintiffs. The resolution will emerge in the appeal, which could take four to six months.

Comments

Post a Comment