A unanimous decision June 13 by the New Jersey Supreme Court, which overruled a loose application of blight in an eminent domain case, doesn’t apply in New York, but it’s still instructive, since state courts often look to trends in other states.

Bottom line: were the lawsuit challenging the Atlantic Yards environmental review transposed to New Jersey, the government would have a much tougher—though perhaps not impossible—task asserting blight.

However, the New York State Legislature and state courts, unlike those in many other states, have been slow to revise eminent domain laws in response to public concern. Blight remains a loosely defined and highly contested issue, as in the hearing May 3 regarding the challenge to the Atlantic Yards environmental impact statement.

A decision is pending in that case. Notably, one of the blight characteristics asserted in Brooklyn--that buildings are unproductive because they don’t fulfill 60% of allowable development rights--likely wouldn't pass muster in New Jersey.

Case history

The summary below is drawn from the syllabus of Gallenthin Realty Development v. Paulsboro, which concerns a challenge brought by longtime owners of a 63-acre plot of land, mostly undeveloped open space, which is bounded by a street, a creek, an industrial facility, and a packaging facility and an inactive British Petroleum (BP) storage site. The state has designated it as protected wetlands. An unused railroad spur traces the property’s western edge and an active gas pipeline bisects the property

At the owner’s request, the Paulsboro Planning Board “rezoned the property in 1998 from manufacturing to marine industrial business park, thereby permitting various commercial, light industrial, and mixed non-residential uses,” according to the syllabus describing the case. (Note that the Atlantic Yards site was not rezoned, though a majority of it, north of the Pacific Street streetbed, sits in the longstanding Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA, which contemplated eminent domain.)

In that same year, the town adopted a new master plan identifying seven broadly defined areas in need of redevelopment. While the Gallenthin property was not included in this plan, in the next year, the board investigated whether several parcels, including the BP site adjacent to the Gallenthin site, could be added to the plan. In 2002, those sites were added.

In 2000, BP and its neighbor Dow commissioned a study of their properties. In 2002, that study suggested adding the Gallenthin property to the BP/Dow redevelopment project, because it provided access routes to the property. The town’s consultant then recommended adding the Gallenthin property to the project, calling it “in need of redevelopment,” thus subject to eminent domain.

Gallenthin challenged that designation, but saw the complaint dismissed in two lower court jurisdictions. However, the Supreme Court held that, because the state authorizes government redevelopment of only “blighted” areas, the Legislature did not intend it to apply in circumstances where the sole argument is that the property is “not fully productive.”

Rather, it applies “only to areas that, as a whole, are stagnant and unproductive because of issues of title, diversity of ownership, or other similar conditions.”

The definition

The court looked to legislative history:

When the Blighted Areas Clause was adopted in 1947, the framers were concerned with addressing the deterioration of certain sections of older cities that were causing an economic domino effect devastating surrounding properties. The Blighted Areas Clause enabled municipalities to intervene, stop further economic degradation, and provide incentives for economic investment. Although the meaning of ‘blight’ has evolved, the term retains its essential characteristic: deterioration or stagnation that negatively affects surrounding properties.

Other states define blight similarly, the court said.

Blight in New York

In New York, the lengthy Urban Development Corporation Act, passed in 1968 with the aim of building low-income housing in the wake of urban riots, uses the term “blighted” as part of a larger definition:

The term "substandard or insanitary area" shall mean and be interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area.

Of course, arguably, the largest contributors to stagnation at the Atlantic Yards site were issues well beyond blight. The state and city never made an effort to market the “blighted” Vanderbilt Yard, as Department of City Planning official Winston Von Engel conceded last year, even though the city, in its PlaNYC sustainability effort, now sees railyards and highway cuts as valuable development sites.

Nor did the city ever seek to encourage development by changing the zoning on the Pacific and Dean street blocks now part of the project footprint; rather, developer Forest City Ratner got a private upzoning, courtesy of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC).

Not fully productive?

In the New Jersey case, Paulsboro argued that the state law “permits redevelopment of any property that is ‘stagnant or not fully productive’ yet potentially valuable for ‘contributing to and serving’ the general welfare.

However, under that approach, any property that is operated in less than optimal manner is arguably ‘blighted,’” the Supreme Court observed.

In the Atlantic Yards case, the ESDC identified several blight characteristics, including “buildings or lots that exhibit signs of significant physical deterioration, vacant lots, buildings that are at least 50% vacant, and lots that are underutilized in that they are built to 60% or less of their floor area ratio [FAR] under current zoning.”

Are properties blighted if they exhibit just one blight characteristic?, asked State Supreme Court Justice Joan A. Madden at the May 3 hearing.

“Yes,” replied ESDC attorney Philip Karmel.

That would theoretically condemn large swaths of Brownstone Brooklyn as blighted, since they’re not built out to 60% of their development rights. But that likely wouldn't pass muster in New Jersey.

Sufficient evidence?

In the New Jersey decision, the Supreme Court concluded that the Legislature intended the law “to apply only to property that has become stagnant because of issues of title, diversity of ownership, or other similar conditions.”

Not only was it insufficient for Paulsboro to say that the land was not fully productive, the court said, “the record contains no evidence suggesting that the Gallenthin property is integral to the larger BP/Dow Redevelopment Area or that the Planning Board based its determination on anything other than the property not being fully productive.”

In Brooklyn, to be sure, the ESDC prepared—well, commissioned--a much more extensive record, a Blight Study of more than 300 pages. And, as the ESDC said in court papers, only once has a state court overturned an agency determination of blight, but in that case, the agency failed to provide “any substantial data at all.” So it's a tough challenge.

Hearing redux

The ESDC, plaintiffs’ attorney Jeff Baker said in court May 3, would not consider a project limited to the railyard because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. That seems contradicted by reality, given the new construction adjacent to the footprint. Rather, it appears that the ESDC wouldn’t consider a project limited to the railyard because it wasn’t the project presented by Forest City Ratner.

And, even though the ESDC states that diversity of ownership means it’s hard to assemble land for the project and thus is an argument for condemnation, that doesn’t mean it would pass muster under the New Jersey decision. After all, the single largest plot, the MTA’s 8.5-acre railyard, presents a significant development opportunity unto itself.

The diversity of ownership issue arises because of Forest City Ratner’s plan to build over 22 acres. The developer chose the footprint, and “the extent of the blight matches the footprint,” Baker said, calling it “the proverbial putting the cart before the horse.”

Despite evidence of new development in Prospect Heights, and newspaper articles about growth there, the ESDC called it speculative to assume the area would improve. In court, Baker was sardonic: “OK, let’s compare our analysis to the market analysis they did. Sorry, I can’t. They never did.”

ESDC defense

Questioning ESDC attorney Karmel at the hearing, Judge Madden asked why most of Block 1128—between Sixth and Carlton avenues, and Pacific and Dean streets, was excluded. “The blight study concerned the footprint of the project,” Karmel responded. How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots beyond the urban renewal area? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded. “It’s a question of reason.”

How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots beyond the urban renewal area? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded. “It’s a question of reason.”

The Blight Study concluded that 51 of 73 parcels, or 79 percent, were blighted. Still, the ESDC did not add an empty lot immediately adjacent to the footprint on Pacific Street just east of Sixth Avenue, while the large grayish building in the right of the photo, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Pacific Street, is occupied and not considered blighted, but is in the footprint.

Drawing the line

“We now hear they don’t like using 60%” of FAR as a criteria for underutilization, Karmel said. “You have to have a cutoff somewhere.”

The ESDC memorandum of law called the agency’s consideration of underutilization, along with other factors, “a permissible exercise of discretion.”

But how draw the line? Interestingly, an ESDC footnote buttressing that argument cites a 1985 case, G&A Books, Inc. v. Stern, which states, “The FEIS treats the severe underuse of the land in the Project Area’s 13 acres as further evidence of blight.”

It's hard to argue that the buildings on the Atlantic Yards site exhibit "severe underuse." According to a law dictionary, “severe” means “of an extreme degree.” A building that occupies 53% of its allowable Floor Area Ratio would not seem to represent “severe underuse.”

As I wrote last August, that 100-foot plot of land just east of Sixth Avenue is apparently needed less to remove blight at that plot than to supply staging and temporary parking.

As I wrote last August, that 100-foot plot of land just east of Sixth Avenue is apparently needed less to remove blight at that plot than to supply staging and temporary parking.

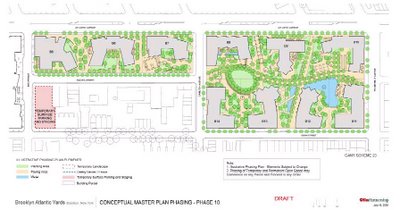

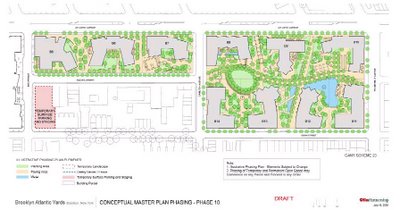

One draft map (right) of the project's master plan shows that parking lot remaining through the construction period; another document suggests the building at the site would be constructed midway through the projected ten-year process.

Blighted or not?

While the plaintiffs in the challenge to the environmental review are organizations and the those in federal court eminent domain challenge are individuals, both are organized primarily by Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and share at least one lawyer and a volunteer legal team.

DDDB filed a fierce response to the ESDC’s Blight Study. In the federal case, the plaintiffs did not concede the site was blighted, and U.S. District Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis, in his opinion, apparently misread the stance,

In the state case, however, the plaintiffs acknowledged in a legal brief the “concededly blighted ATURA portion,” as the ESDC points out.

Drawing the boundaries

That inconsistency shouldn't affect the state case. There, the plaintiffs focused on the blight designation outside the longstanding ATURA blocks, the properties on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street.

So the case may hinge on whether the judge thinks there was anything fishy about the map drawn by Forest City Ratner and ESDC.

In defense of the map, the ESDC noted that “blight findings have consistently been upheld where the subject property(s) had not previously been included within an urban renewal area.” Indeed, not all properties must be blighted if, as stated in a previous decision, they are “necessary for effective rehabilitation of an area as a whole.”

(Emphases added)

Later in the memorandum, the ESDC repeated that “the test is as to the area as a unit.” Moreover, the ESDC cited the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Berman v. Parker eminent domain case, which deferred to the legislative judgment that the area “must be planned as a whole.”

That raises the question: is the “area” in the Atlantic Yards case ATURA? The northern blocks of Prospect Heights? Or just the project footprint Forest City Ratner seeks?

In a footnote, the ESDC shows its hand:

Although the issue is not disputed by Petitioners, it bears noting that the FEIS documents the importance of the parcels lying to the south of Pacific Street to the Project…. integral to the construction of a properly designed arena.

In other words, the “area” means the project. Elsewhere in the memo, the ESDC fudges the distinction, arguing that “the focus of the inquiry should be the entire Project area.”

But the Blight Study concerned the footprint, and the footprint only, and it's a rather curious "unit," to use the ESDC's test. That's why the omission of most of Dean and Pacific streets between Sixth and Carlton avenues--the block that contains the Newswalk condos, among other thriving properties--must be something the judge grapples with in her decision.

Bottom line: were the lawsuit challenging the Atlantic Yards environmental review transposed to New Jersey, the government would have a much tougher—though perhaps not impossible—task asserting blight.

However, the New York State Legislature and state courts, unlike those in many other states, have been slow to revise eminent domain laws in response to public concern. Blight remains a loosely defined and highly contested issue, as in the hearing May 3 regarding the challenge to the Atlantic Yards environmental impact statement.

A decision is pending in that case. Notably, one of the blight characteristics asserted in Brooklyn--that buildings are unproductive because they don’t fulfill 60% of allowable development rights--likely wouldn't pass muster in New Jersey.

Case history

The summary below is drawn from the syllabus of Gallenthin Realty Development v. Paulsboro, which concerns a challenge brought by longtime owners of a 63-acre plot of land, mostly undeveloped open space, which is bounded by a street, a creek, an industrial facility, and a packaging facility and an inactive British Petroleum (BP) storage site. The state has designated it as protected wetlands. An unused railroad spur traces the property’s western edge and an active gas pipeline bisects the property

At the owner’s request, the Paulsboro Planning Board “rezoned the property in 1998 from manufacturing to marine industrial business park, thereby permitting various commercial, light industrial, and mixed non-residential uses,” according to the syllabus describing the case. (Note that the Atlantic Yards site was not rezoned, though a majority of it, north of the Pacific Street streetbed, sits in the longstanding Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA, which contemplated eminent domain.)

In that same year, the town adopted a new master plan identifying seven broadly defined areas in need of redevelopment. While the Gallenthin property was not included in this plan, in the next year, the board investigated whether several parcels, including the BP site adjacent to the Gallenthin site, could be added to the plan. In 2002, those sites were added.

In 2000, BP and its neighbor Dow commissioned a study of their properties. In 2002, that study suggested adding the Gallenthin property to the BP/Dow redevelopment project, because it provided access routes to the property. The town’s consultant then recommended adding the Gallenthin property to the project, calling it “in need of redevelopment,” thus subject to eminent domain.

Gallenthin challenged that designation, but saw the complaint dismissed in two lower court jurisdictions. However, the Supreme Court held that, because the state authorizes government redevelopment of only “blighted” areas, the Legislature did not intend it to apply in circumstances where the sole argument is that the property is “not fully productive.”

Rather, it applies “only to areas that, as a whole, are stagnant and unproductive because of issues of title, diversity of ownership, or other similar conditions.”

The definition

The court looked to legislative history:

When the Blighted Areas Clause was adopted in 1947, the framers were concerned with addressing the deterioration of certain sections of older cities that were causing an economic domino effect devastating surrounding properties. The Blighted Areas Clause enabled municipalities to intervene, stop further economic degradation, and provide incentives for economic investment. Although the meaning of ‘blight’ has evolved, the term retains its essential characteristic: deterioration or stagnation that negatively affects surrounding properties.

Other states define blight similarly, the court said.

Blight in New York

In New York, the lengthy Urban Development Corporation Act, passed in 1968 with the aim of building low-income housing in the wake of urban riots, uses the term “blighted” as part of a larger definition:

The term "substandard or insanitary area" shall mean and be interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area.

Of course, arguably, the largest contributors to stagnation at the Atlantic Yards site were issues well beyond blight. The state and city never made an effort to market the “blighted” Vanderbilt Yard, as Department of City Planning official Winston Von Engel conceded last year, even though the city, in its PlaNYC sustainability effort, now sees railyards and highway cuts as valuable development sites.

Nor did the city ever seek to encourage development by changing the zoning on the Pacific and Dean street blocks now part of the project footprint; rather, developer Forest City Ratner got a private upzoning, courtesy of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC).

Not fully productive?

In the New Jersey case, Paulsboro argued that the state law “permits redevelopment of any property that is ‘stagnant or not fully productive’ yet potentially valuable for ‘contributing to and serving’ the general welfare.

However, under that approach, any property that is operated in less than optimal manner is arguably ‘blighted,’” the Supreme Court observed.

In the Atlantic Yards case, the ESDC identified several blight characteristics, including “buildings or lots that exhibit signs of significant physical deterioration, vacant lots, buildings that are at least 50% vacant, and lots that are underutilized in that they are built to 60% or less of their floor area ratio [FAR] under current zoning.”

Are properties blighted if they exhibit just one blight characteristic?, asked State Supreme Court Justice Joan A. Madden at the May 3 hearing.

“Yes,” replied ESDC attorney Philip Karmel.

That would theoretically condemn large swaths of Brownstone Brooklyn as blighted, since they’re not built out to 60% of their development rights. But that likely wouldn't pass muster in New Jersey.

Sufficient evidence?

In the New Jersey decision, the Supreme Court concluded that the Legislature intended the law “to apply only to property that has become stagnant because of issues of title, diversity of ownership, or other similar conditions.”

Not only was it insufficient for Paulsboro to say that the land was not fully productive, the court said, “the record contains no evidence suggesting that the Gallenthin property is integral to the larger BP/Dow Redevelopment Area or that the Planning Board based its determination on anything other than the property not being fully productive.”

In Brooklyn, to be sure, the ESDC prepared—well, commissioned--a much more extensive record, a Blight Study of more than 300 pages. And, as the ESDC said in court papers, only once has a state court overturned an agency determination of blight, but in that case, the agency failed to provide “any substantial data at all.” So it's a tough challenge.

Hearing redux

The ESDC, plaintiffs’ attorney Jeff Baker said in court May 3, would not consider a project limited to the railyard because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. That seems contradicted by reality, given the new construction adjacent to the footprint. Rather, it appears that the ESDC wouldn’t consider a project limited to the railyard because it wasn’t the project presented by Forest City Ratner.

And, even though the ESDC states that diversity of ownership means it’s hard to assemble land for the project and thus is an argument for condemnation, that doesn’t mean it would pass muster under the New Jersey decision. After all, the single largest plot, the MTA’s 8.5-acre railyard, presents a significant development opportunity unto itself.

The diversity of ownership issue arises because of Forest City Ratner’s plan to build over 22 acres. The developer chose the footprint, and “the extent of the blight matches the footprint,” Baker said, calling it “the proverbial putting the cart before the horse.”

Despite evidence of new development in Prospect Heights, and newspaper articles about growth there, the ESDC called it speculative to assume the area would improve. In court, Baker was sardonic: “OK, let’s compare our analysis to the market analysis they did. Sorry, I can’t. They never did.”

ESDC defense

Questioning ESDC attorney Karmel at the hearing, Judge Madden asked why most of Block 1128—between Sixth and Carlton avenues, and Pacific and Dean streets, was excluded. “The blight study concerned the footprint of the project,” Karmel responded.

How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots beyond the urban renewal area? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded. “It’s a question of reason.”

How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots beyond the urban renewal area? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded. “It’s a question of reason.”The Blight Study concluded that 51 of 73 parcels, or 79 percent, were blighted. Still, the ESDC did not add an empty lot immediately adjacent to the footprint on Pacific Street just east of Sixth Avenue, while the large grayish building in the right of the photo, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Pacific Street, is occupied and not considered blighted, but is in the footprint.

Drawing the line

“We now hear they don’t like using 60%” of FAR as a criteria for underutilization, Karmel said. “You have to have a cutoff somewhere.”

The ESDC memorandum of law called the agency’s consideration of underutilization, along with other factors, “a permissible exercise of discretion.”

But how draw the line? Interestingly, an ESDC footnote buttressing that argument cites a 1985 case, G&A Books, Inc. v. Stern, which states, “The FEIS treats the severe underuse of the land in the Project Area’s 13 acres as further evidence of blight.”

It's hard to argue that the buildings on the Atlantic Yards site exhibit "severe underuse." According to a law dictionary, “severe” means “of an extreme degree.” A building that occupies 53% of its allowable Floor Area Ratio would not seem to represent “severe underuse.”

As I wrote last August, that 100-foot plot of land just east of Sixth Avenue is apparently needed less to remove blight at that plot than to supply staging and temporary parking.

As I wrote last August, that 100-foot plot of land just east of Sixth Avenue is apparently needed less to remove blight at that plot than to supply staging and temporary parking.One draft map (right) of the project's master plan shows that parking lot remaining through the construction period; another document suggests the building at the site would be constructed midway through the projected ten-year process.

Blighted or not?

While the plaintiffs in the challenge to the environmental review are organizations and the those in federal court eminent domain challenge are individuals, both are organized primarily by Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and share at least one lawyer and a volunteer legal team.

DDDB filed a fierce response to the ESDC’s Blight Study. In the federal case, the plaintiffs did not concede the site was blighted, and U.S. District Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis, in his opinion, apparently misread the stance,

In the state case, however, the plaintiffs acknowledged in a legal brief the “concededly blighted ATURA portion,” as the ESDC points out.

Drawing the boundaries

That inconsistency shouldn't affect the state case. There, the plaintiffs focused on the blight designation outside the longstanding ATURA blocks, the properties on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street.

So the case may hinge on whether the judge thinks there was anything fishy about the map drawn by Forest City Ratner and ESDC.

In defense of the map, the ESDC noted that “blight findings have consistently been upheld where the subject property(s) had not previously been included within an urban renewal area.” Indeed, not all properties must be blighted if, as stated in a previous decision, they are “necessary for effective rehabilitation of an area as a whole.”

(Emphases added)

Later in the memorandum, the ESDC repeated that “the test is as to the area as a unit.” Moreover, the ESDC cited the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Berman v. Parker eminent domain case, which deferred to the legislative judgment that the area “must be planned as a whole.”

That raises the question: is the “area” in the Atlantic Yards case ATURA? The northern blocks of Prospect Heights? Or just the project footprint Forest City Ratner seeks?

In a footnote, the ESDC shows its hand:

Although the issue is not disputed by Petitioners, it bears noting that the FEIS documents the importance of the parcels lying to the south of Pacific Street to the Project…. integral to the construction of a properly designed arena.

In other words, the “area” means the project. Elsewhere in the memo, the ESDC fudges the distinction, arguing that “the focus of the inquiry should be the entire Project area.”

But the Blight Study concerned the footprint, and the footprint only, and it's a rather curious "unit," to use the ESDC's test. That's why the omission of most of Dean and Pacific streets between Sixth and Carlton avenues--the block that contains the Newswalk condos, among other thriving properties--must be something the judge grapples with in her decision.

Comments

Post a Comment