Finally the epic Atlantic Yards story has been given some sustained attention, in New York magazine political reporter Chris Smith’s cover story, Mr. Ratner’s Neighborhood, subtitled “Manipulative developers, shrill protesters, and a sixteen-tower glass-and-steel monster marching inexorably forward.”

Finally the epic Atlantic Yards story has been given some sustained attention, in New York magazine political reporter Chris Smith’s cover story, Mr. Ratner’s Neighborhood, subtitled “Manipulative developers, shrill protesters, and a sixteen-tower glass-and-steel monster marching inexorably forward.”Smith, who lives in Fort Greene, writes that he’d stayed out of the debate, having “shrugged off the complaints of Atlantic Yards opponents as shrill and reflexively obstructionist.”

But after immersing himself in the story, he comes out deeply troubled. While he acknowledges the concerns and claims of supporters, he's not fully convinced of the benefits, and, above all, he concludes that the project is profoundly undemocratic. It's a notable counterpoint to the credulous, compromised, and contradictory New York Times editorial published yesterday.

Smith does make a few small errors, some of which I’ll mention, but he gets the big picture and, in some instances, adds to it.

The big picture

The big pictureFirst, he sees what's at stake:

As a political reporter, I know that money and spin usually win. But in looking at Atlantic Yards up close, it’s outrageous to see the absolute absence of democratic process. There’s been no point in the past four years at which the public has been given a meaningful chance to decide whether something this big and transformative should be built on public property. Instead, race, basketball, and Frank Gehry have been tossed out as distractions to steer attention away from the real issue, money. Ratner’s team has mounted an elaborate road show before community boards and local groups, at which people have been allowed to ask questions and vent, and the developer has made a grand show of listening, then tinkering around the edges. But the fundamentals of the project—an arena plus massive residential and commerical buildings—has never been up for discussion. Ratner, with Gehry’s aid, has built a titanium-clad, irregularly angled tank and driven it relentlessly through a gauntlet of neighborhood slingshots. And Bloomberg and Pataki—our only elected officials with the power to force a real debate about Atlantic Yards—instead jumped aboard early and fastened their seat belts. What at first seemed to me impressive on a clinical level—a developer’s savvy use of state-of-the-art political tactics—ends up being, on closer inspection, positively chilling.

Indeed, it’s the first time someone in the mainstream media has made much of an effort to analyze the content of the developer’s tactics, not merely the phenomenon of them. The New York Times ran two stories, one in October 2005, and another in June 2005, that described but did not evaluate those tactics.

Smith could have made an even stronger case had he pointed out the contrast with the current plans to develop the MTA’s Hudson Yards—with the city willing to solicit bids from developers—or the accelerated schedule for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement, a process has raised qualms even among some project supporters, like Eliot Spitzer.

Also, he could have observed, when mentioning (twice) the “seven acres of publicly-accessible open space,” that it would be far less than what the city recommends for the population the project would bring.

A sense of scale

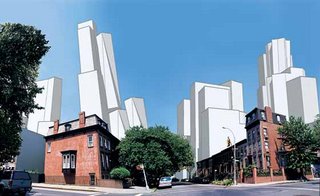

In a second important contribution, the article opens with a rendering (above) of what the project would look like from the adjacent neighborhood, skyscrapers as viewed from a row-house scale. Will James of OnNYTurf offered such renderings in March, and Forest City Ratner followed with its own renderings—some of them rather deceptive—in May.

But the New York Times hasn’t printed such crucial images and, on the day, the new project design was released, printed a photo of three project principals in front of an out-of-context rendering.

But the New York Times hasn’t printed such crucial images and, on the day, the new project design was released, printed a photo of three project principals in front of an out-of-context rendering. And Smith's article takes the issue to another level by illustrating (right) the shadows the buildings might cast. (Any shadow imaging analysis is somewhat complicated because shadows would fall for only certain hours.)

Profit projections

Third, Smith attempts an educated guess regarding Ratner’s projected profits: $1 billion, according to a reading of Ratner’s nearly-illegible and brief pro-forma cash flow statement filed with the MTA, or $700 million to $1 billion according to “real-estate expert Jeffrey Jackson” (whose firm specializes in appraisals).

That's a 25% profit, the article says, but maybe it's more if you calculate the variety of tax breaks. The point is that the financial analysis deserves greater discussion.

Does a 25% profit mean that the project could be reduced only by a relatively small amount for the developer to be comfortable? This is a variant of FCR's statement that the infrastructure costs require a certain scale for profit. But that's backwards--the city could have, as it has proposed for the Hudson Yards, absorbed some of the infrastructure costs and then put the property out for bid, rather than let the developer determine the scale.

Green and the opera

Assemblyman Roger Green offers a notable misreading of race and class:

“Here’s the question: If we were building an 18,000-seat opera house, would we get as much resistance? I don’t think so. Basketball is like a secular religion for most Brooklynites. The opposition to the arena is actually coming from people who are new to Brooklyn, who lived in Manhattan, mostly. And who have a culture of opposing projects of this nature. People who opposed the West Side Highway project; people who opposed the Jets stadium; people who opposed a host of other things. That’s the reality. There’s a class of people who are going to the opera. And there’s another class of folks who will go to a basketball game and get a cup of beer.”

Well, I’ll point to my recent piece listing the numerous opponents, including two former Black Panthers, who hardly fit Green’s stereotypes.

Also, the issue isn’t the arena, it’s how the arena has been used to get politicians and the public on board for the larger project, which includes 16 towers. The arena would be only about one-tenth of the entire project.

(For those who are curious: I’ve never lived in Manhattan. I’ve rented in Brooklyn for about 15 years, and basketball is my favorite sport. My criticism of this project comes from looking at it closely.)

On the CBA

Smith allows that the Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) includes “terrific and creative commitments”—well, perhaps not, as the New York Observer has written--but that the payments to community groups mean that critics say the “community” has been bought.

While that’s not untrue, it’s another example in which “critics” bring up a point that the reporter could make independently; as I’ve noted several times, in Los Angeles, where CBAs have been pioneered, signatories don’t take money from developers.

Some footnotes

Some issues are so compressed as to require footnotes. Smith writes:

Still, forming a clear-cut opinion isn’t easy. Ratner is building subsidized housing in a city where there’s a cruel 3 percent vacancy rate.

But public subsidies would support the housing, and those subsidies could be used to build housing elsewhere.

He continues:

He’s forecasting $1.5 billion in new tax revenues for the city and 3,800 new permanent jobs.

Actually, he’s forecasting $2.1 billion in new tax revenue to the city and the state over 30 years, and about $1.5 billion in net revenue. Of course those numbers can be challenged. And the number of jobs would be far fewer than previously promised.

Smith offers a first-impression misdescription of the site:

Most of the site for the proposed project, the Long Island Rail Road yards, is quite literally a hole in the ground, flanked by a number of decaying buildings.

Hold on. The railyards would be about 8.3 acres of a 22-acre site. Some of the buildings are decaying, some are not, and some have been recently rehabilitated.

Smith also describes the project site as a Brooklyn neighborhood defined by four-story brownstones.

Well, mainly brownstones, though there are taller industrial buildings, some converted to housing, in the footprint, and even taller buildings nearby across some major thoroughfares.

"One unknown man"

Smith devotes several paragraphs to my work, calling me “one unknown man.” (Hey, what happened to “obscure”? Anyhow, some know me as the "Mad Overkiller.")

He also dubs me “the opposition’s greatest resource.” I wouldn’t claim that, especially since I aim to be a resource for the general public discussion of the project.

But I would aim to be, as described, "a skeptic in the tradition of I.F. Stone." I told Smith I was inspired by Stone, who found good stories in overlooked documents.

I've raised numerous issues independently, but some of the findings attributed to me—the fact that 15,000 construction jobs are actually 15,000 job years, or the fact that the developer’s purported scaleback was nothing of the sort—were not exclusive to me. The Brooklyn Papers, for example, first raised the construction jobs issue, though I've repeatedly reminded readers of it.

As for the residential density, I’ll take credit for coining the phrase “extreme density,” but the cogent point that the project would be double the next densest census tract should be attributed to the New York Observer’s Matthew Schuerman.

Smith later in the article refers to “density trivia,” which unfortunately trivializes the issue. The details are important, because few people are against density at a site that could support some significant density; the question is how much.

It's too bad that Smith didn't mention the role of NoLandGrab, which is a comprehensive compilation, with commentary and analysis, of nearly every scrap published related to the Atlantic Yards issue.

The point is that the media coverage has been inadequate, so unknown critics create their own media, a counternarrative--more analytical and accurate, I'd say--to the picture drawn by the media, the politicians, and the developer.

Reading the DEIS

Smith makes a yeoman effort to try to translate the bureaucratic language of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) to on-the-ground reality. Would subway service be fine? Not in Smith’s test of the Atlantic Avenue station.

What does it mean, regarding traffic, to experience a “significant adverse impact” at an intersection? Delays greater than 80 seconds per vehicle. Smith offers a simple way to think about it: count how long cars typically wait before their drivers start honking.

As for the proposed mitigation for public schools, scattering the new students across two school districts, Smith suggests that, in human terms, that could cause chaos.

ACORN's challenge

Bertha Lewis of ACORN offers a challenge: “Talk to me about what your resolution is to the resegregation of Brooklyn.” She's right to point out that any development should have affordable housing, especially given the failure to include it in much new development.

But should the presence of affordable housing, as Ron Shiffman writes, “become the stalking horse for an ill-conceived development”?

And would this project stop gentrification or contribute to it?

"A bad deal"

Smith, who acknowledges his family is a cliché—they bought a brownstone in Fort Greene in the 90s after moving from Manhattan post-parenthood—may come off to some as an I-got-mine homeowner concerned about the traffic on his block. But he defends against that:

I care plenty about tomorrow for myself and for the city. And no matter how I look at it, in the end, I can only conclude that Atlantic Yards is a bad deal.

After observing that the issue is money, he offers a cold-water corrective from a Democrat who says that the project is a fait accompli. However, Smith concludes:

The small warm neighborhoods around Atlantic Yards will become moons orbiting a cold planet. Shadows and noise can be modeled on computers, but their emotional effects can’t.

Brooklyn is changing every day, all the time; I wouldn’t want to live here if it didn’t. I don’t kid myself that all the changes are “organic” or even desirable. But it’s an evolution instead of a cataclysm imposed from above. The opposition to Ratnerville is sometimes vitriolic, unsympathetic, irrational. Sign me up.

It is a testament to the "voice" allowed in magazine journalism that Smith could (mostly) try to evaluate conclusions himself, without feeling obligated to balance every quote from each side, as "objective" newspaper coverage too often must attempt.

Who's in charge?

The fundamental issue isn't Forest City Ratner. Any developer would press its advantage, with varying degrees of sincerity, dexterity, and deviousness.

To engage some key constituencies and to do the right thing, FCR has agreed to union labor and environmental sustainability, and to some degree of affordable housing and job training. Meanwhile, it has issued deceptive brochures, claimed community consultation when it didn't exist, and (likely) sponsored a disturbing push-poll.

But in the end, our government officials are responsible--or not.

Comments

Post a Comment