So what helped revive the neighborhoods around Downtown Brooklyn in the 1960s and 1970s? If you read Chapter 1, Project Description, of the Atlantic Yards Draft Environmental Impact Statement, you'd conclude that somehow it was governmental investment in urban renewal, including condemnation.

And if you read the Chapter 7, Cultural Resources, the same message recurs. (The chapters are embedded below.)

But unacknowledged is the parallel process in Brownstone Brooklyn of mostly private reinvestment and revival via historic preservation, which was hastened by the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission.

A segment in Chapter 1 titled FOCUS ON RENEWAL (1960-2000) begins with this long paragraph about city programs to reinvest in struggling neighborhoods:

The situation in the area surrounding (and including) the project site, as well as other areas of Brooklyn and throughout the city continued to worsen into the 1970s. Buildings were abandoned and burned, and the city lost more than 800,000 residents. City policy focused on stemming the tide of disinvestment, first through urban renewal, supported by a range of subsidized housing programs available at the time primarily through the federal government. Beginning in the late 1970s, under Mayor Koch, the City began an aggressive program of housing renewal. Using a range of financing options and funding sources, the City developed a variety of programs, all geared to support the reclamation of its damaged neighborhoods. These programs used properties acquired primarily by foreclosure on properties in tax arrears and also through condemnation, and they were responsible for preserving, renovating, and rebuilding more than 150,000 housing units. This effort resulted in marked improvements in several low-income neighborhoods, including Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bushwick, and East New York. Today, nearly all of the in rem (tax-foreclosed) properties have been reclaimed—in August 2005, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) issued its last major RFP (Request for Proposals) for developers to create housing on City-owned land taken in rem.

What about historic districts?

There's more to the story, which seems written to argue for major government action. The neighborhoods mentioned above are farther away from the proposed Atlantic Yards site than several historic districts, the rise of which goes unmentioned.

There's more to the story, which seems written to argue for major government action. The neighborhoods mentioned above are farther away from the proposed Atlantic Yards site than several historic districts, the rise of which goes unmentioned.

Constrast the DEIS with a 1974 city study, titled Preliminary Study of Feasibility: Brooklyn Sports Complex (available in the New York Public Library), which set the context for a proposed arena development. (The 1974 study is cited in the Project Description chapter regarding Coney Island.) It states:

Downtown Brooklyn is almost totally surrounded by reviving brownstone residential neighborhoods. Of the five distinct neighborhoods that ring the downtown, four have been cited by the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission for their outstanding examples of 19th century townhouse architecture and have been designated Historic Districts. These four neighborhoods are Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, and Park Slope. The fifth neighborhood, Fort Greene, has applied for landmark designation and is expected to be honored with a designation in the near future. The Historic District designation carries with it a requirement for authentic restoration and preservation.

These four neighborhoods are Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, and Park Slope. The fifth neighborhood, Fort Greene, has applied for landmark designation and is expected to be honored with a designation in the near future. The Historic District designation carries with it a requirement for authentic restoration and preservation.

Note: Fort Greene was designated as a city Historic District in 1978, as was the Brooklyn Academy of Music Historic District. Clinton Hill was designated in 1981. Prospect Heights was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

It's all urban renewal

The DEIS, in the second and final paragraph in the Focus on Renewal section, focuses on urban renewal, but not the buildings at right (which are just below the renewal zone):

The DEIS, in the second and final paragraph in the Focus on Renewal section, focuses on urban renewal, but not the buildings at right (which are just below the renewal zone):

During this period, the City continued to use the planning and development powers of urban renewal as a tool for reversing the decline in its communities. In the late 1960s/early 1970s, several urban renewal plans were mapped in Downtown Brooklyn. Of these, the ATURA Plan (1968) applied directly to portions of the project site (see Figure 1-2). All of the blocks touching Atlantic Avenue on the project site form the southern boundary of the urban renewal area, which extends northward in an irregular shape to Hanson Place/Greene Avenue, and encompasses all or portions of the four blocks on both sides of Flatbush Avenue between Pacific Street and Lafayette Avenue. ATURA, which has been amended 10 times in the past 35 years, began as an ambitious plan to move the Fort Greene Meat Market to Sunset Park, demolish deteriorating housing and replace it with 2,400 units; and build a new Baruch College campus to span the rail yard on the project site and Atlantic Avenue; a high school (also over the LIRR tracks), other schools, parks, and shopping. Over the years, the plan underwent a number of changes, reflecting the improving real estate market in the area in the 1980s and the realities of the public’s inability to fund major construction projects, such as the Baruch College plan. Today, virtually all of the urban renewal area north of Atlantic Avenue has been redeveloped. Some 1,300 housing units have been built, either directly by a public agency (i.e., the New York City Housing Authority [NYCHA] and the New York City Housing Development Corporation [HDC]) or by a non-profit entity using public subsidies. Major retail development has taken place along Atlantic Avenue at and near Flatbush Avenue, and a large office building, the Bank of New York Tower, sits above a shopping mall above the LIRR Atlantic Terminal. Only the blocks on the southern side of Atlantic Avenue, hampered by the difficulty in building over the LIRR rail yard (which the urban renewal plan recognized in its Fourth Amendment [1976] when it removed the railroad sites from the list of properties to be acquired), have resisted development. At this point, the project site’s depressed rail yard and dilapidated, vacant, and underutilized properties perpetuate a visual and physical barrier between the redeveloped areas to the north of Atlantic Avenue and the neighborhoods to the south.

ATURA, which has been amended 10 times in the past 35 years, began as an ambitious plan to move the Fort Greene Meat Market to Sunset Park, demolish deteriorating housing and replace it with 2,400 units; and build a new Baruch College campus to span the rail yard on the project site and Atlantic Avenue; a high school (also over the LIRR tracks), other schools, parks, and shopping. Over the years, the plan underwent a number of changes, reflecting the improving real estate market in the area in the 1980s and the realities of the public’s inability to fund major construction projects, such as the Baruch College plan. Today, virtually all of the urban renewal area north of Atlantic Avenue has been redeveloped. Some 1,300 housing units have been built, either directly by a public agency (i.e., the New York City Housing Authority [NYCHA] and the New York City Housing Development Corporation [HDC]) or by a non-profit entity using public subsidies. Major retail development has taken place along Atlantic Avenue at and near Flatbush Avenue, and a large office building, the Bank of New York Tower, sits above a shopping mall above the LIRR Atlantic Terminal. Only the blocks on the southern side of Atlantic Avenue, hampered by the difficulty in building over the LIRR rail yard (which the urban renewal plan recognized in its Fourth Amendment [1976] when it removed the railroad sites from the list of properties to be acquired), have resisted development. At this point, the project site’s depressed rail yard and dilapidated, vacant, and underutilized properties perpetuate a visual and physical barrier between the redeveloped areas to the north of Atlantic Avenue and the neighborhoods to the south.

Note that the focus then was on government and nonprofit entities building subsidized housing.

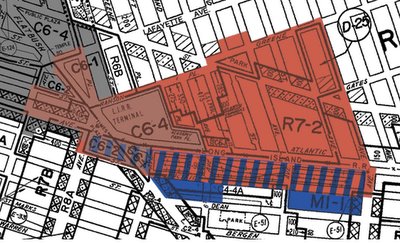

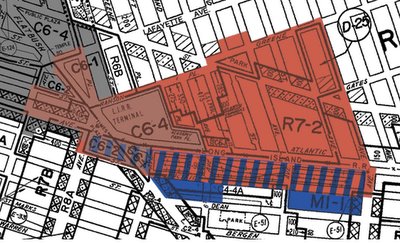

[In the map above, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street, but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Just outside ATURA

Unmentioned are the conversions of former manufacturing/warehouse buildings in and around the proposed Atlantic Yards site, including the Newswalk building (not in the footprint) that dominates Pacific Street between Sixth and Carlton Avenues, the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street, and the former Spalding factory at 24 Sixth Avenue. (The latter two are pictured one paragraph up.) Also unmentioned is the potential to adapt other intact buildings, notably the Ward Bakery (third building, in background) and another former manufacturing plant (foreground).

Unmentioned are the conversions of former manufacturing/warehouse buildings in and around the proposed Atlantic Yards site, including the Newswalk building (not in the footprint) that dominates Pacific Street between Sixth and Carlton Avenues, the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street, and the former Spalding factory at 24 Sixth Avenue. (The latter two are pictured one paragraph up.) Also unmentioned is the potential to adapt other intact buildings, notably the Ward Bakery (third building, in background) and another former manufacturing plant (foreground).

Cultural resources

And here are the final two (of three total) paragraphs in a section of the Cultural Resources chapter headlined CONTINUED 20th CENTURY DEVELOPMENT:

Following World War II, the elevated subway lines were demolished (including the Fulton Street elevated subway just prior to the war in 1941)—an action which would have been expected to improve the area. However, this coincided with a middle class exodus to the suburbs. As lower-income groups moved into the residential neighborhoods, rowhouses became rooming houses and many were abandoned. In Prospect Heights, Washington Avenue was the site of riots and arson that destroyed many buildings in the 1960s. The industrial district along Atlantic Avenue also began to decline as much of the area’s manufacturing base moved out. The Fort Greene meat market was no longer able to meet federal meat packing standards. Also, there were a large number of abandoned and structurally unsound buildings.

In response to these conditions, the City created the Fort Greene Meat Market Urban Renewal Area in the 1960s. Five years later, it was renamed the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). The goals of the ATURA Plan were to encourage development and employment opportunities in the area; create new housing of high quality and/or rehabilitated housing of upgraded quality; and provide community facilities, parks, retail shopping, and parking. Slowed down by the City’s financial crisis in the 1970s and amended many times, all of the new development north of Atlantic Avenue between Flatbush and Carlton Avenues is attributable to ATURA, including the large-scale commercial development at Atlantic Center, and the streets of small-scale rowhouses on South Oxford Street, Cumberland Street, and Carlton Avenue that are reminiscent of the surrounding historic residential neighborhoods.

Again, this is a very narrow view, focusing strictly on the project site and adjacent blocks. Move a few more blocks and the historic districts emerge.

Acknowledgement elsewhere

It's not that the authors of the DEIS don't know the history. Chapter 16, Neighborhood Character, does acknowledge the surrounding neighborhoods:

In contrast to the underutilization that characterizes much of the project site, the surrounding area includes portions of several distinct and vibrant neighborhoods containing well-defined building types, streetscapes and densities, including Boerum Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights, and Park Slope. However, the character of these neighborhoods changes as they approach the project site. The areas closer to the project site lack the cohesive character of the cores of their neighborhoods, indicative of the transitional character of these areas.

Well, the "transitional character" of the real estate to the north of the project site is because of urban renewal--for example, land cleared for the Atlantic Center mall--while the "transitional character" of the neighborhood south of the railyard was in the process of being transformed privately, thanks to some spot rezoning before the Atlantic Yards plan was announced.

The question is how to transform the transition. What might have happened had the city sought a rezoning--as it did for the Greenpoint/Williamsburg waterfront--rather than embrace one plan that would override zoning?

01_ProjectDescription DEIS

07 Cultural DEIS

16_NeighborhoodCharacter DEIS

And if you read the Chapter 7, Cultural Resources, the same message recurs. (The chapters are embedded below.)

But unacknowledged is the parallel process in Brownstone Brooklyn of mostly private reinvestment and revival via historic preservation, which was hastened by the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission.

A segment in Chapter 1 titled FOCUS ON RENEWAL (1960-2000) begins with this long paragraph about city programs to reinvest in struggling neighborhoods:

The situation in the area surrounding (and including) the project site, as well as other areas of Brooklyn and throughout the city continued to worsen into the 1970s. Buildings were abandoned and burned, and the city lost more than 800,000 residents. City policy focused on stemming the tide of disinvestment, first through urban renewal, supported by a range of subsidized housing programs available at the time primarily through the federal government. Beginning in the late 1970s, under Mayor Koch, the City began an aggressive program of housing renewal. Using a range of financing options and funding sources, the City developed a variety of programs, all geared to support the reclamation of its damaged neighborhoods. These programs used properties acquired primarily by foreclosure on properties in tax arrears and also through condemnation, and they were responsible for preserving, renovating, and rebuilding more than 150,000 housing units. This effort resulted in marked improvements in several low-income neighborhoods, including Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bushwick, and East New York. Today, nearly all of the in rem (tax-foreclosed) properties have been reclaimed—in August 2005, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) issued its last major RFP (Request for Proposals) for developers to create housing on City-owned land taken in rem.

What about historic districts?

There's more to the story, which seems written to argue for major government action. The neighborhoods mentioned above are farther away from the proposed Atlantic Yards site than several historic districts, the rise of which goes unmentioned.

There's more to the story, which seems written to argue for major government action. The neighborhoods mentioned above are farther away from the proposed Atlantic Yards site than several historic districts, the rise of which goes unmentioned.Constrast the DEIS with a 1974 city study, titled Preliminary Study of Feasibility: Brooklyn Sports Complex (available in the New York Public Library), which set the context for a proposed arena development. (The 1974 study is cited in the Project Description chapter regarding Coney Island.) It states:

Downtown Brooklyn is almost totally surrounded by reviving brownstone residential neighborhoods. Of the five distinct neighborhoods that ring the downtown, four have been cited by the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission for their outstanding examples of 19th century townhouse architecture and have been designated Historic Districts.

These four neighborhoods are Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, and Park Slope. The fifth neighborhood, Fort Greene, has applied for landmark designation and is expected to be honored with a designation in the near future. The Historic District designation carries with it a requirement for authentic restoration and preservation.

These four neighborhoods are Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, and Park Slope. The fifth neighborhood, Fort Greene, has applied for landmark designation and is expected to be honored with a designation in the near future. The Historic District designation carries with it a requirement for authentic restoration and preservation.Note: Fort Greene was designated as a city Historic District in 1978, as was the Brooklyn Academy of Music Historic District. Clinton Hill was designated in 1981. Prospect Heights was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

It's all urban renewal

The DEIS, in the second and final paragraph in the Focus on Renewal section, focuses on urban renewal, but not the buildings at right (which are just below the renewal zone):

The DEIS, in the second and final paragraph in the Focus on Renewal section, focuses on urban renewal, but not the buildings at right (which are just below the renewal zone):During this period, the City continued to use the planning and development powers of urban renewal as a tool for reversing the decline in its communities. In the late 1960s/early 1970s, several urban renewal plans were mapped in Downtown Brooklyn. Of these, the ATURA Plan (1968) applied directly to portions of the project site (see Figure 1-2). All of the blocks touching Atlantic Avenue on the project site form the southern boundary of the urban renewal area, which extends northward in an irregular shape to Hanson Place/Greene Avenue, and encompasses all or portions of the four blocks on both sides of Flatbush Avenue between Pacific Street and Lafayette Avenue.

ATURA, which has been amended 10 times in the past 35 years, began as an ambitious plan to move the Fort Greene Meat Market to Sunset Park, demolish deteriorating housing and replace it with 2,400 units; and build a new Baruch College campus to span the rail yard on the project site and Atlantic Avenue; a high school (also over the LIRR tracks), other schools, parks, and shopping. Over the years, the plan underwent a number of changes, reflecting the improving real estate market in the area in the 1980s and the realities of the public’s inability to fund major construction projects, such as the Baruch College plan. Today, virtually all of the urban renewal area north of Atlantic Avenue has been redeveloped. Some 1,300 housing units have been built, either directly by a public agency (i.e., the New York City Housing Authority [NYCHA] and the New York City Housing Development Corporation [HDC]) or by a non-profit entity using public subsidies. Major retail development has taken place along Atlantic Avenue at and near Flatbush Avenue, and a large office building, the Bank of New York Tower, sits above a shopping mall above the LIRR Atlantic Terminal. Only the blocks on the southern side of Atlantic Avenue, hampered by the difficulty in building over the LIRR rail yard (which the urban renewal plan recognized in its Fourth Amendment [1976] when it removed the railroad sites from the list of properties to be acquired), have resisted development. At this point, the project site’s depressed rail yard and dilapidated, vacant, and underutilized properties perpetuate a visual and physical barrier between the redeveloped areas to the north of Atlantic Avenue and the neighborhoods to the south.

ATURA, which has been amended 10 times in the past 35 years, began as an ambitious plan to move the Fort Greene Meat Market to Sunset Park, demolish deteriorating housing and replace it with 2,400 units; and build a new Baruch College campus to span the rail yard on the project site and Atlantic Avenue; a high school (also over the LIRR tracks), other schools, parks, and shopping. Over the years, the plan underwent a number of changes, reflecting the improving real estate market in the area in the 1980s and the realities of the public’s inability to fund major construction projects, such as the Baruch College plan. Today, virtually all of the urban renewal area north of Atlantic Avenue has been redeveloped. Some 1,300 housing units have been built, either directly by a public agency (i.e., the New York City Housing Authority [NYCHA] and the New York City Housing Development Corporation [HDC]) or by a non-profit entity using public subsidies. Major retail development has taken place along Atlantic Avenue at and near Flatbush Avenue, and a large office building, the Bank of New York Tower, sits above a shopping mall above the LIRR Atlantic Terminal. Only the blocks on the southern side of Atlantic Avenue, hampered by the difficulty in building over the LIRR rail yard (which the urban renewal plan recognized in its Fourth Amendment [1976] when it removed the railroad sites from the list of properties to be acquired), have resisted development. At this point, the project site’s depressed rail yard and dilapidated, vacant, and underutilized properties perpetuate a visual and physical barrier between the redeveloped areas to the north of Atlantic Avenue and the neighborhoods to the south.Note that the focus then was on government and nonprofit entities building subsidized housing.

[In the map above, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street, but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Just outside ATURA

Unmentioned are the conversions of former manufacturing/warehouse buildings in and around the proposed Atlantic Yards site, including the Newswalk building (not in the footprint) that dominates Pacific Street between Sixth and Carlton Avenues, the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street, and the former Spalding factory at 24 Sixth Avenue. (The latter two are pictured one paragraph up.) Also unmentioned is the potential to adapt other intact buildings, notably the Ward Bakery (third building, in background) and another former manufacturing plant (foreground).

Unmentioned are the conversions of former manufacturing/warehouse buildings in and around the proposed Atlantic Yards site, including the Newswalk building (not in the footprint) that dominates Pacific Street between Sixth and Carlton Avenues, the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street, and the former Spalding factory at 24 Sixth Avenue. (The latter two are pictured one paragraph up.) Also unmentioned is the potential to adapt other intact buildings, notably the Ward Bakery (third building, in background) and another former manufacturing plant (foreground).Cultural resources

And here are the final two (of three total) paragraphs in a section of the Cultural Resources chapter headlined CONTINUED 20th CENTURY DEVELOPMENT:

Following World War II, the elevated subway lines were demolished (including the Fulton Street elevated subway just prior to the war in 1941)—an action which would have been expected to improve the area. However, this coincided with a middle class exodus to the suburbs. As lower-income groups moved into the residential neighborhoods, rowhouses became rooming houses and many were abandoned. In Prospect Heights, Washington Avenue was the site of riots and arson that destroyed many buildings in the 1960s. The industrial district along Atlantic Avenue also began to decline as much of the area’s manufacturing base moved out. The Fort Greene meat market was no longer able to meet federal meat packing standards. Also, there were a large number of abandoned and structurally unsound buildings.

In response to these conditions, the City created the Fort Greene Meat Market Urban Renewal Area in the 1960s. Five years later, it was renamed the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). The goals of the ATURA Plan were to encourage development and employment opportunities in the area; create new housing of high quality and/or rehabilitated housing of upgraded quality; and provide community facilities, parks, retail shopping, and parking. Slowed down by the City’s financial crisis in the 1970s and amended many times, all of the new development north of Atlantic Avenue between Flatbush and Carlton Avenues is attributable to ATURA, including the large-scale commercial development at Atlantic Center, and the streets of small-scale rowhouses on South Oxford Street, Cumberland Street, and Carlton Avenue that are reminiscent of the surrounding historic residential neighborhoods.

Again, this is a very narrow view, focusing strictly on the project site and adjacent blocks. Move a few more blocks and the historic districts emerge.

Acknowledgement elsewhere

It's not that the authors of the DEIS don't know the history. Chapter 16, Neighborhood Character, does acknowledge the surrounding neighborhoods:

In contrast to the underutilization that characterizes much of the project site, the surrounding area includes portions of several distinct and vibrant neighborhoods containing well-defined building types, streetscapes and densities, including Boerum Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights, and Park Slope. However, the character of these neighborhoods changes as they approach the project site. The areas closer to the project site lack the cohesive character of the cores of their neighborhoods, indicative of the transitional character of these areas.

Well, the "transitional character" of the real estate to the north of the project site is because of urban renewal--for example, land cleared for the Atlantic Center mall--while the "transitional character" of the neighborhood south of the railyard was in the process of being transformed privately, thanks to some spot rezoning before the Atlantic Yards plan was announced.

The question is how to transform the transition. What might have happened had the city sought a rezoning--as it did for the Greenpoint/Williamsburg waterfront--rather than embrace one plan that would override zoning?

01_ProjectDescription DEIS

07 Cultural DEIS

16_NeighborhoodCharacter DEIS

Comments

Post a Comment