To supporters of Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards project, it's a long-awaited plan for long-overlooked land. "The Atlantic Yards area has been available for any developer in America for over 100 years,” declared Borough President Marty Markowitz at a 5/26/05 City Council hearing.

Charles Gargano, chairman of the Empire State Development Corporation, mused on 11/15/05 to WNYC's Brian Lehrer, “Isn’t it interesting that these railyards have sat for decades and decades and decades, and no one has done a thing about them.” Forest City Ratner spokesman Joe DePlasco, in a 12/19/04 New York Times article ("In a War of Words, One Has the Power to Wound") described the railyards as "an empty scar dividing the community."

But why exactly has the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard never been developed? Do public officials have some responsibility?

But why exactly has the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard never been developed? Do public officials have some responsibility?

At a hearing yesterday of the Brooklyn Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee, Kate Suisman, aide to Council Member Letitia James, honed in on the question. The topic was land use, and Winston Von Engel, Deputy Director of the Department of City Planning's Brooklyn office, was on the hot seat in the Borough Hall courtroom. (Photo from Dope on the Slope.)

"Just to be clear, this was a project that was initiated by the developer--is that right?" asked Suisman, whose boss is the leading public official opposed to Forest City Ratner's project.

"That's our understanding," Von Engel replied. (Well, Markowitz approached developer Bruce Ratner with the idea of bringing a basketball team to Brooklyn, and the developer recognized that a standalone arena wouldn't make economic sense.)

"Had the city been looking at making use of the land?" Suisman pressed on politely.

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said. He noted that there were once plans decades ago for a campus for Baruch College of the City University of New York, as part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). "This area was looked at in a very large context. What survived was the Atlantic Center mall [pictured], the Atlantic Terminal mall, the housing. So, in that sense there were plans at one point, but some of them were not realized."

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said. He noted that there were once plans decades ago for a campus for Baruch College of the City University of New York, as part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). "This area was looked at in a very large context. What survived was the Atlantic Center mall [pictured], the Atlantic Terminal mall, the housing. So, in that sense there were plans at one point, but some of them were not realized."

He cited a recent rezoning for the Newswalk building--condos built out of an old Daily News manufacturing plant that sits on a piece of land sliced out of the Atlantic Yards footprint--and noted that other property owners in Prospect Heights had begun to convert industrial buildings to residential ones.

Suisman continued: Was there a reason the city didn't take a look at the area?

"We didn't decide to take a look at the yards," Von Engel replied. "They belong to the Long Island Rail Road. They use them heavily. They're critical to their operations. You do things in a step-by-step process. We concentrated on the Downtown Brooklyn development plan for Downtown Brooklyn. Forest City Ratner owns property across the way. And they saw the yards, and looked at those. We had not been considering the yards directly."

At the head of the table, Markowitz looked a bit pained, as a woman young enough to be his daughter educed the city's diffidence in developing the site. There were fewer than ten people in the audience, and maybe a dozen public officials, aides, and community board representatives around the table. It was another episode in the Atlantic Yards Committee's curious mix of impotence and importance.

Was there ever an RFP? Remember, Andrew Alper, president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, told City Council at a 5/4/04 hearing: So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and try to find a better deal.

The importance of context

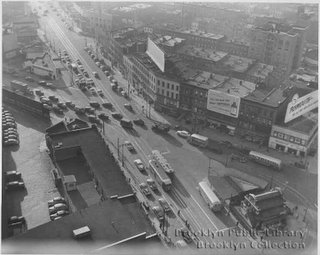

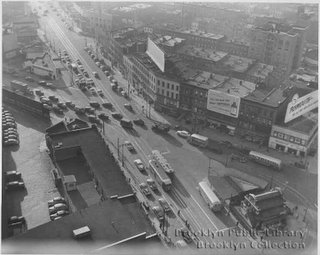

Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards proposal must be seen in context with other nearby projects, many of which did not come into fruition until the past decade, after the area rebounded economically. The blocks around the railyards--the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--have been in various stages of decline, clearance, and renewal. As the photo at right (updated: taken sometime after the 1988 demolition of the Flatbush Terminal and before the mid-90s construction on urban renewal land) suggests, large lots of land north of Atlantic Avenue (the northern border of the railyards) were scars themselves, decades after urban renewal began. The urban renewal land had to become scarce enough for a developer to target the railyards, which require a platform for construction. (Also, the railyard function must be moved nearby.)

Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards proposal must be seen in context with other nearby projects, many of which did not come into fruition until the past decade, after the area rebounded economically. The blocks around the railyards--the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--have been in various stages of decline, clearance, and renewal. As the photo at right (updated: taken sometime after the 1988 demolition of the Flatbush Terminal and before the mid-90s construction on urban renewal land) suggests, large lots of land north of Atlantic Avenue (the northern border of the railyards) were scars themselves, decades after urban renewal began. The urban renewal land had to become scarce enough for a developer to target the railyards, which require a platform for construction. (Also, the railyard function must be moved nearby.)

The photo at right, picturing mid-2005 conditions, was taken after the openings of the Atlantic Center mall (1996) and the Atlantic Terminal mall (2004). (Photos from Forest City Ratner presentation to City Council on 5/26/05.)

The photo at right, picturing mid-2005 conditions, was taken after the openings of the Atlantic Center mall (1996) and the Atlantic Terminal mall (2004). (Photos from Forest City Ratner presentation to City Council on 5/26/05.)

The city’s clearance of substandard housing and relocation of the Fort Greene Meat Market led—eventually--to major changes. More than two decades before the malls, the major construction in the ATURA consisted of six subsidized apartment buildings, five up to 15 stories high, and one that's 31 stories high. In the mid-1990s, as the first mall was being constructed, different kinds of subsidized housing--numerous row houses--were constructed, and later a seven-story building for senior citizens was built. (The photo is taken from the Sixth Avenue bridge, over the railyards, approaching Atlantic Avenue and looking northeast.)

Over the years, though, more ambitious projects fell by the wayside, including a development with new office towers, a possible sports arena, and a new campus for Baruch College of City University of New York, to be built over the railyards.

Over the years, though, more ambitious projects fell by the wayside, including a development with new office towers, a possible sports arena, and a new campus for Baruch College of City University of New York, to be built over the railyards.

A good part of the problem was money. A city plan to move Baruch College to a parcel that included the railyards was stalled in 1973, as the city lacked $27 million (some $120 million in March 2006 dollars) to build a platform for new construction. Last year, the MTA estimated the cost of a platform and a new yard at $56-$72 million, though bidders Extell and Forest City Ratner estimated higher costs.

Nearby, new homeowners invested in row-house blocks; the Fort Greene Historic District was designated in 1978. The president of the Downtown Brooklyn Development Association as saying the brownstoners helped usher in business and government investment, according to a 6/9/77 article in the Brooklyn Phoenix quoted by geographer Winifred Curran in her analysis of ATURA (see below). Some neighborhood residents also resisted major development projects, fearing congestion and crime. Echoes of the Atlantic Yards controversy? Partly--but the scale of the new plan is far larger.

ATURA boundaries

More than half of the Atlantic Yards footprint, including the railyard, would fall within the boundaries of ATURA, a more than 40-year-old experiment in urban planning. The 104-acre site (originally 85 acres) is located mostly in Fort Greene, including the sites that became the Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center malls north of Atlantic Avenue, plus a variety of subsidized housing, including high-rises and row houses.

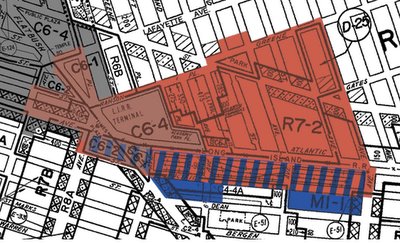

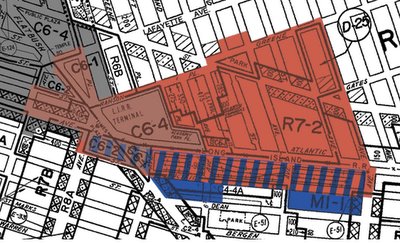

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street (but not the buildings on the south side of the street).

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street (but not the buildings on the south side of the street).

ATURA includes the segments of the Atlantic Yards plan between Pacific and Atlantic: the railyards and the two plots of land to the west, which Site 6-A, the triangle of land between Fifth, Atlantic, and Flatbush Avenues, and Site 5, now occupied by P.C. Richard/Modell's, and a community garden. The latter two were originally in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, but were excised because they overlapped with the Atlantic Yards plan. They are arguably the only segments of the Atlantic Yards plan that are in Downtown Brooklyn--unless the concept of downtown is extended. (Site 5, which is south of Flatbush Avenue, might be said to be in Park Slope, while Site 6-A might be said to be in Prospect Heights.)

ATURA includes the segments of the Atlantic Yards plan between Pacific and Atlantic: the railyards and the two plots of land to the west, which Site 6-A, the triangle of land between Fifth, Atlantic, and Flatbush Avenues, and Site 5, now occupied by P.C. Richard/Modell's, and a community garden. The latter two were originally in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, but were excised because they overlapped with the Atlantic Yards plan. They are arguably the only segments of the Atlantic Yards plan that are in Downtown Brooklyn--unless the concept of downtown is extended. (Site 5, which is south of Flatbush Avenue, might be said to be in Park Slope, while Site 6-A might be said to be in Prospect Heights.)

Dodger hopes

Brooklyn went into decline in the 1950s, as suburbs drew people and businesses, and government agencies let banks redline neighborhoods to stymie investment. Even before ATURA, some big plans were floated. In early 1954, according to Michael Shapiro’s book “The Last Good Season,” the president of the New York Council of Wholesale Meat Dealers wrote to Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, asking for help in relocating the “vast and fetid Fort Greene Meat Market,” which was deteriorating rapidly.

Brooklyn went into decline in the 1950s, as suburbs drew people and businesses, and government agencies let banks redline neighborhoods to stymie investment. Even before ATURA, some big plans were floated. In early 1954, according to Michael Shapiro’s book “The Last Good Season,” the president of the New York Council of Wholesale Meat Dealers wrote to Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, asking for help in relocating the “vast and fetid Fort Greene Meat Market,” which was deteriorating rapidly.

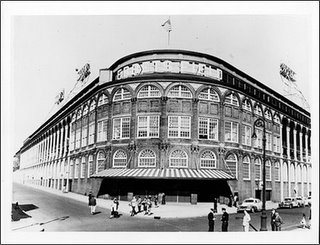

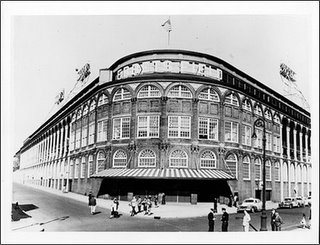

The location “sat above the Brooklyn terminus of the Long Island Rail Road,” Shapiro wrote. (Actually, it was to the east nearby.) It represented a solution for Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, whose Ebbets Field in the Flatbush neighborhood was small and antiquated, with limited access to parking and public transit. (Photo from Brooklyn Eagle via Brooklyn Public Library.)

“It was impossible to envision a better site for a new Brooklyn ballpark,” Shapiro wrote, channeling Cashmore’s observations. Robert Moses, the city’s planning czar, however, wanted a new stadium at Flushing Meadows, near a highway and accessible to suburbanites—which he eventually got.

“It was impossible to envision a better site for a new Brooklyn ballpark,” Shapiro wrote, channeling Cashmore’s observations. Robert Moses, the city’s planning czar, however, wanted a new stadium at Flushing Meadows, near a highway and accessible to suburbanites—which he eventually got.

Moses, according to Shapiro, opposed Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley’s desire to use public money or governmental condemnation powers to build the stadium at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. Roger Kahn, in his book, “The Era,” added that Moses thought there would be too much traffic at the site—an issue that recurs today. (Photo of the crossroads of Flatbush and Atlantic, looking southeast, in 1947, from the Brooklyn Public Library's Brooklyn Eagle collection. The roof of the Long Island Rail Road station is in the lower left. That is now the site of the Atlantic Terminal mall.)

ATURA emerges

In 1962, according to a 9/5/65 New York Times article, “the City Planning Commission recommended a sweeping $150 million redevelopment and rehabilitation program for the area surrounding the Long Island terminal at Atlantic Avenue.” (By the way, $150 million in 1962 dollars would be nearly $1 billion in March 2006 dollars.) “Known as the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, the plan included the removal of the Fort Greene Meat Market, an antiquated wholesale market behind the terminal, the clearance of slums and the construction of low-income and middle income apartment houses and industrial buildings."

That 1965 New York Times article, headlined “Vacant Store Windows Stare At Once-Bustling Flatbush Ave.,” painted a grim picture, citing 43 empty storefronts between DeKalb Avenue and Grand Army Plaza. A city spokesman said—presciently, it turns out—“that it would be ‘literally years’ before any physical change would be made.” A local businessman—again presciently—wondered why the area was in decline. “We’ve got everything in the way of transportation here,” said Frederick Kriete, assistant vice-president of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. “It’s a little Times Square.”

For another history of ATURA, see this animated timeline produced by the Center for Urban Pedagogy. I can't confirm all the facts/dates, but much is consonant with the information below.

Baruch mentions

By 1968, there were inklings of change, with redevelopment to be anchored by education. The Times reported, in a 4/17/68 article headlined “Sale of L.I.U. Site Opposed by Mayor,” that, according to one CUNY source, Mayor John Lindsay supported a new site for Manhattan’s Baruch College “within a triangular-shaped area bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, in the Crown Heights section.” Though the exact location was not specified, the site, south of Atlantic Avenue, would apparently have included the railyards. (Crown Heights? Apparently not everyone was calling it Prospect Heights.)

By 1968, there were inklings of change, with redevelopment to be anchored by education. The Times reported, in a 4/17/68 article headlined “Sale of L.I.U. Site Opposed by Mayor,” that, according to one CUNY source, Mayor John Lindsay supported a new site for Manhattan’s Baruch College “within a triangular-shaped area bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, in the Crown Heights section.” Though the exact location was not specified, the site, south of Atlantic Avenue, would apparently have included the railyards. (Crown Heights? Apparently not everyone was calling it Prospect Heights.)

A 6/24/68 Times article, headlined “Renewal Raises Brooklyn Hopes,” described the city’s urban renewal plan as $250 million (over $1.4 billion in March 2006 dollars). It portrayed some serious blight:

The pavement smells of rancid fat on a warm day and the meat cutting continues through the night. The plants are surrounded by residential houses.

Three blocks of open railroad tracks alongside Atlantic Avenue and an abandoned railroad loading platform, where vagrants, addicts and drunks sleep and prostitutes congregate even during the day.

Houses that in the words of Borough President Abe Stark are ‘unfit for human habitation.'

The renewal plan, according to the Times, “calls for 2,400 new low- and middle-income housing units to replace 800 dilapidated units, removal of the blighting Fort Greene Meat Market, a 14-acre site for the City University’s new Baruch College, two new parks and community facilities such as day-care centers.”

Meat market moves

The meat market lingered. On 10/24/68, the Times reported, the city had decided to move the market to an area between the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges, which has since become the upscale neighborhood known as DUMBO. Otis Pratt Pearsall of the Municipal Art Society called it “an outrageous misuse of a prime section of river frontage.” On 2/8/69, the Times reported, five Brooklyn Heights homeowners, supported by the Brooklyn Heights Association, sued to block the move, saying that the site—defunct Civil War-era warehouses-—should be developed into housing and recreation.

Some six months later, on 8/19/69, the Times reported that the city had chosen a site in Sunset Park, apparently responding to the criticism. But the move came slowly. In early 1975, the Times was predicting a move that spring; on 7/14/76, the Times reported that the market remained unfinished because the builder was in default.

Subsidized housing plans

While the subsidized housing didn't arrive until 1976, plans emerged years before that. A 9/23/70 article in the Times described plans to build a 300-unit public housing project on a 2.2-acre between Carlton Avenue and Adelphi Street and between Atlantic Avenue in Fulton Street, near the eastern end of ATURA. It was initially described as a 20-story building, but it ultimately became Atlantic Terminal Site 4B, a 31-story building and the tallest city housing project, built just north of Atlantic Avenue between Clermont and Carlton Avenues.

While the subsidized housing didn't arrive until 1976, plans emerged years before that. A 9/23/70 article in the Times described plans to build a 300-unit public housing project on a 2.2-acre between Carlton Avenue and Adelphi Street and between Atlantic Avenue in Fulton Street, near the eastern end of ATURA. It was initially described as a 20-story building, but it ultimately became Atlantic Terminal Site 4B, a 31-story building and the tallest city housing project, built just north of Atlantic Avenue between Clermont and Carlton Avenues.

A 10/31/71 article, headlined “Rebuilding To Start at L.I.R. Area in Brooklyn,” cited plans to begin that building “next spring,” and plans to building 2,400 housing units “and a $97 million new home for Baruch College to straddle Atlantic Avenue.” (That’s $475 million in March 2006 dollars.) The college buildings “would be built on air rights over the Long Island’s underground train shed and underground storage yards.” Along Flatbush Avenue, the area “has become so blighted that a commuters’ bar near the station keeps its door locked at night and customers are admitted only after scrutiny by the bartender.” Meanwhile, construction had been scheduled for a replacement meat market located in Sunset Park—not the area that would become DUMBO—though it would take years to complete.

In late 1972, the City Planning Commission approved plans to construct five moderate-income buildings. "Although some elected officials are urging caution and review, I say six years of study, planning and review have already gone by and this project must be approved now," the former chairman of Community Board 2, Roy Vanasco, told the Times (Planners Approve 2 Projects in Brooklyn, 12/17/72).

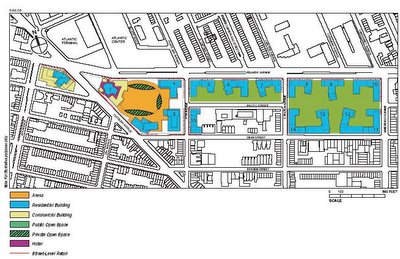

A 1/27/73 article in the Times, headlined “Housing is Voted for Fort Greene,” described plans to construct those five buildings. Two of them, 12 and 15 stories high, would be “in the middle of the block bounded by Hanson Place, North Portland Avenue, Atlantic Avenue and South Elliott Place.” These (right) are the Atlantic Terminal I coops, a 15-story building on South Portland Avenue and a 12-story building on South Elliott Place. These are just north of the southeast segment of the Atlantic Center mall. (The mall lacks entrances near those towers; blame fear of local youths and others. In the background is the Bank of New York tower on top of the Atlantic Terminal mall, built in 2004.)

A 1/27/73 article in the Times, headlined “Housing is Voted for Fort Greene,” described plans to construct those five buildings. Two of them, 12 and 15 stories high, would be “in the middle of the block bounded by Hanson Place, North Portland Avenue, Atlantic Avenue and South Elliott Place.” These (right) are the Atlantic Terminal I coops, a 15-story building on South Portland Avenue and a 12-story building on South Elliott Place. These are just north of the southeast segment of the Atlantic Center mall. (The mall lacks entrances near those towers; blame fear of local youths and others. In the background is the Bank of New York tower on top of the Atlantic Terminal mall, built in 2004.)

The second project, Atlantic Terminal II, was to consist of three buildings, 9, 13, and 15 stories high, near the Atlantic Terminal 4B building. Ultimately, the project, on Carlton Avenue and Fulton Street, included one 15-story coop and two 13-story buildings, known as Atlantic Terminal II. They are Mitchell-Lama buildings.

The site clearance required significant urban renewal. In a 6/17/73 article headlined “Brooklyn Renewal Slowly Advances,” the Times noted that the city had acquired 461 buildings, demolishing most of them, and had 200 more buildings slated for condemnation. Some 375 businesses and 750 families had been moved, with another 75 businesses and 165 families slated to move.

The site clearance required significant urban renewal. In a 6/17/73 article headlined “Brooklyn Renewal Slowly Advances,” the Times noted that the city had acquired 461 buildings, demolishing most of them, and had 200 more buildings slated for condemnation. Some 375 businesses and 750 families had been moved, with another 75 businesses and 165 families slated to move.

Arena hopes

That 1/27/73 article reported that Brooklyn Borough President Sebastian Leone “urged the rebuilding of the Long Island Rail Road terminal at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues and the construction of a new hotel, a sports arena and other facilities in the area.”

More than a year later, in a 7/17/74 article, Leone was reported to promote his idea before the New York State Sports Authority. The article, headlined “Arena Plan Is Pressed in Brooklyn,” noted that community opponents preferred low income housing and expressed fears of traffic jams and air pollution.

Residents even sued to block a proposed $50,000 feasibility study of a 15,000 seat arena, according to a 2/23/75 article headlined "Brooklyn Arena Study Halted." But when the suit was withdrawn, lawyers representing the city and state said the study wouldn't proceed anyhow, since the state's Sport Authority was expected to be abolished. The suit was to represent homeowners from Bensonhurst, Bay Ridge, Coney Island, and the Atlantic Terminal area. Leone said he didn't think the oft-mentioned Atlantic Terminal area was in fact the best location. "And anyway," he told the newspaper, "we have plans for housing there." A representative of a Fort Greene group fighting the arena supported "additional middle-income cooperative housing."

The possibility of an arena occasionally revived. A 6/6/84 article in the Times, headlined, “Site Near Shea Favored For Domed Stadium,” cited discussions about a new arena “in the Atlantic Terminal area of Brooklyn, at the site of Aqueduct Race Track in Queens, or near Shea Stadium.”

Ultimately, as an 8/25/91 Newsday article reported, proponents of the Brooklyn Sportsplex, as the 1990s version of the project was known, decided to push for an indoor arena and outdoor stadium in Coney Island. “There were just too many people who didn’t want it there,” said Robert Zeig of the Brooklyn Sports Foundation, referring to an arena in ATURA.

A new Baruch site, and fiscal crisis

Meanwhile, Baruch’s plans were on hold, as a CUNY spokesman said in the 1/27/73 article that the Board of Higher Education decided to keep the college in Manhattan “after learning it would cost $27 million just to build a platform of the Long Island Rail Road tracks on which to construct the college.”

But there was more space in ATURA. In 12/4/73 article in the Times, headlined “Beame Is Said to Favor the ‘Concept’ Of Moving Baruch College to Brooklyn,” Borough President Leone said that, because the originally proposed site posed an engineering difficulty, Baruch would then be offered a different site, covering 10 acres.

A year later, in a 12/18/74 article headlined “Baruch College Will Be Moved To $73 Million Site in Brooklyn,” the Times reported that the college would move to a 15-acre site north of the railyards, bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Fulton Street, Carlton Avenue, South Oxford Street and South Portland Avenue. The scheduled completion date was 1980. While the exact dimensions are unclear, that is roughly the area east of (but perhaps including part of) the Atlantic Center mall—an area later slated for subsidized low-rise housing.

A 1/16/75 article, headlined “New Campus in Brooklyn Wins Support,” pointed out that the project would “probably halve the 2,400 moderate income housing units planned.” Speakers at a City Planning Commission hearing “expressed concern that additional units might be sacrificed for a proposed Brooklyn sports arena.”

Six weeks later, a 3/2/75 article about the City Planning Commission, headlined “Do-It-Yourself Plan For Garage Killed,” offered slightly different boundaries for the Baruch plan: Atlantic Avenue, Fulton Street, Carlton Avenue, Hanson Place, and Flatbush Avenue.”

The project seemed to be moving ahead. A 3/7/75 article, headlined “Board of Estimate Votes Tunnel-Work Compromise,” reported that the Board of Estimate, then a crucial layer in city government, approved street closings and zoning changes for the Baruch campus, after agreeing to reserve an adjacent parcel for additional low- and moderate-income housing. A 3/19/75 Times article ("New Baruch College Site Approved") reported that the city's Site Selection Board signed off on the location, but city and state budget officials still needed to approve the plans before architects could get to work.

Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable surveyed the plans for Baruch and commercial redevelopment, and citing ongoing neighborhood renewal in a 3/30/75 article buoyantly headlined "The Blooming of Downtown Brooklyn."

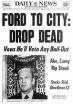

Not so fast. The Baruch move became a casualty of the city’s fiscal crisis. (That famous New York Daily News headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” ran on 10/30/75.) A 3/18/77 article in the Times, “Atlantic Avenue to Bloom Anew In a Brooklyn Restorer’s Plan,” pointed out that work in ATURA had stalled. “But the city’s financial plight has set back hopes for a new Baruch College campus in the City University system, financial problems have delayed the move of the Fort Greene meat market, and prospects for new housing at present are dim.”

Not so fast. The Baruch move became a casualty of the city’s fiscal crisis. (That famous New York Daily News headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” ran on 10/30/75.) A 3/18/77 article in the Times, “Atlantic Avenue to Bloom Anew In a Brooklyn Restorer’s Plan,” pointed out that work in ATURA had stalled. “But the city’s financial plight has set back hopes for a new Baruch College campus in the City University system, financial problems have delayed the move of the Fort Greene meat market, and prospects for new housing at present are dim.”

80s ambitions

By the 1980s, plans grew more ambitious. A 6/1/84 Times article headlined, “Brooklyn Uplift: Hotel Reborn as Apartment House,” described changes around the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Fort Greene. It noted how “the main governmental interest now is the development of new office space on urban renewal tracts to create ‘back office’ white collar jobs.”

This was because Jersey City had begun to attract jobs from Manhattan--which was countered, ultimately, by Forest City Ratner's MetroTech development downtown. “For example, a long block to the south of the academy, at the Brooklyn terminus of the Long Island Rail Road, is an immense undeveloped track in the Atlantic Terminal urban renewal area. There is potential for 1 million to 1.5 million square feet of office space and 700 to 1,000 housing units there.”

Meanwhile, smaller-scale development proceeded. A development of 13 3.5-story buildings, including 98 units, was planned as infill housing on Fulton Street, Gates Avenue, and Adelphi Street “along the perimeter of the still largely undeveloped Atlantic Terminal urban renewal area,” according to a 11/9/84 article in the Times headlined “Brownstone Look Returning in Fort Greene Project.” The article pointed out that the buildings required city and federal subsidies: “As with much land in the city’s inventory, values in the neighborhood are not strong enough to generate speculative construction.”

It should be noted that the Fort Greene Historic District had been established in 1978; the counterpart in adjacent Clinton Hill was established in 1981. Owners of buildings in historic districts get a tax break for fixing up their buildings and must get permission to change the look of those buildings; the designation generally serves as a rising tide for property values. Now, speculative construction is common.

1985: big plans emerge

In early 1985, according to a 1/17/85 Times article headlined “Office-Housing Plan for Downtown Brooklyn,” Mayor Ed Koch and business leaders announced a $255 million office/retail/housing complex in ATURA. (That would be $470 million in March 2006 dollars.) The article pointed out that ATURA “was declared an urban renewal zone in 1968 but has never had any major construction, has been singled out by the city as a site for back-office space for Manhattan businesses.”

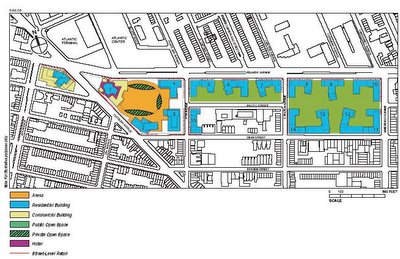

The project would create 1,680 jobs and have two phases. The first phase, over 18 acres, would include 600,000 square feet of office space, 400 housing units—geared at low and middle-income people—a movie theater, and a supermarket. The second phase would include 1.2 million square feet of office space. When the developer, Rose Associates, completed the second stage, it could develop an additional 1.2 million square feet of office and retail space nearby.

The project, the Times wrote (Developers Turn Sights To City's Outer Boroughs, 5/12/85) was a consequence of the rise in Manhattan rents. Also announced was the construction of MetroTech, a joint veture between Forest City Enterprises (the parent company of what would be called Forest City Ratner Companies) and Polytechnic Institute of New York.

More details emerged six months later. According to a 7/31/85 Times article (Brooklyn Plan: Retail Center And 2 Towers), two Art Deco-influenced office towers of about 20 stories would rise across from the Williamsburg Savings Bank. There would be 260 town houses with 600 units, thanks to city and federal subsidies. Ultimately, it would include 3.1 million square feet of office and retail space. The city promised a favorable lease and tax abatements. A neighborhood leader worried that the proposed 1000 parking spaces "would flood the areas with cars and pollution," and that the proposed movie theater would show pornographic movies. (Developer Jonathan Rose said porn would be verboten.)

1986: new plans, urban design

"Give Central Brooklyn a Boost," declared the Times in a 9/24/86 editorial. (Apparently this was not always "near Downtown Brooklyn.") "Despite the gentrification of nearby neighbohroods, Brooklyn's Atlantic Terminal district has for nearly 20 years remained the home of rundown bars and fast-food joints, a hangout for prostitutes and low-lifes."

Not everyone was happy. A few days later (A Plan for Brooklyn Rises at Atlantic Terminal, 9/28/86), opponents said the tax-supported project would encroach on nearby commercial strips and that the townhouses would be out of the financial reach of most area reasidents. (They were aimed at families earning $25,000 to $48,000 a year--or about $45,000 to $87,000 in current dollars.)

The plans evolved. The Board of Estimate, the Times reported 11/16/86, had approved a $500 million project, including 1.8 million square feet of office and commercial space, a public garage, and 12 acres for residential development. (That’s over $900 million in March 2006 dollars.) Some 643 apartments would be built in “attached brownstone-like buildings” over 12 acres, eith exterior stoops, bay windows and architectural detailing. Buildings would enclose private landscape spaces. The design, said the Times in an article headlined “Creating an Urban Neighborhood,” “is an imaginative building pattern… and it is achieved without street closings that would isolate the community from its surroundings.”

The planner for this, hired by Rose Associates, was Peter Calthorpe, who had then done the master plan for the Capitol area of Sacramento, CA and had written a book called “Sustainable Communities,” published by the Sierra Club. More recently, he was hired by Forest City Enterprises, the parent company of Forest City Ratner, for the Stapleton development in Denver. He was cited by the Park Slope Civic Council last year as the type of urban planner who should hired to improve the Atlantic Yards project.

But roadblocks emerged. A Fort Greene block association and other homeowners sued over an environmental impact statement that failed to consider how rerouted traffic would affect their neighborhood, even though it is one block form the project (Brooklyn Residents Sue Rose, 7/19/87).

Then an economic downturn compounded community opposition. The Times reported (Office Growth Slows in Boroughs Outside Manhattan, 2/15/88) that the stock market collapse had deterred office construction. "A lot of people are reassessing their expansion plans," James Stuckey, president of the city's Public Development Corporation, told the Times. (Yes, the same Jim Stuckey, now VP for Forest City Ratner, who told the Times last November that "Projects change, markets change.")

Despite the Board of Estimate’s eventual approval, lawsuits stalled the project. A Times article (Transforming Downtown Brooklyn, 1/22/89) reported that MeteroTech was proceeding but Atlantic Center was blocked in court. The issues: traffic, air quality, and displacement. Even if the suits were resolved, the developer acknowledged, construction would not begin until an anchor tenant emerged.

1990s: malls emerge

A few years later, Forest City Enterprises, the Times reported ('Other Boroughs' Strategy Bucks Difficult Times, 3/10/91), had joined Rose Associates as partner in the project. Eventually, Atlantic Center morphed from an office complex to a mall, and Forest City Ratner became the sole developer. Brooklyn, it turns out, may not have been the place for new office development, but it certainly lacked retail, as FCR figured out. (Even today, as the changes to Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards plan suggest, housing is a better bet than office space.)

A few years later, Forest City Enterprises, the Times reported ('Other Boroughs' Strategy Bucks Difficult Times, 3/10/91), had joined Rose Associates as partner in the project. Eventually, Atlantic Center morphed from an office complex to a mall, and Forest City Ratner became the sole developer. Brooklyn, it turns out, may not have been the place for new office development, but it certainly lacked retail, as FCR figured out. (Even today, as the changes to Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards plan suggest, housing is a better bet than office space.)

A 6/27/93 Times article, “Retailing Opens a New Front in Brooklyn,” pointed to plans by Forest City Ratner to build a store for Bradlees in ATURA, part of the Atlantic Center project. It pointed to a “drastically diminished” development compared to the plan from the 1980s, with no more office towers.

A 6/10/94 article in the Times cited 53 three-family homes being building “on a slice of an empty 24-acre site in Fort Greene.” No longer were duplex condos planned; the new houses “are more marketable and more compatible with the existing neighborhoods,” said a housing official. Ultimately, the Village at Atlantic Center, also known as Atlantic Commons, involved 139 three-family homes totaling 417 units, with brick fronts and cornices meant to invoke the row house neighborhood nearby.

Now, however, plans are more ambitious. The Atlantic Yards plan would place high-rise towers across the street. And, as noted in the “secret” Memorandum of Understanding unveiled last August by Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, Forest City Ratner retains the option to build high-rise office and residential towers on the site of the Atlantic Center mall, which is widely considered an example of poor urban planning. The mall opened in 1996, thanks to considerable subsidies.(Photo from Brooklyn Views.)

Now, however, plans are more ambitious. The Atlantic Yards plan would place high-rise towers across the street. And, as noted in the “secret” Memorandum of Understanding unveiled last August by Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, Forest City Ratner retains the option to build high-rise office and residential towers on the site of the Atlantic Center mall, which is widely considered an example of poor urban planning. The mall opened in 1996, thanks to considerable subsidies.(Photo from Brooklyn Views.)

[Correction: Forest City Ratner has always had the option to build towers on the Atlantic Center site; the memorandum of understanding allows the transfer of a portion of those development right to Site 5.]

One recent building that aimed to harmonize with the neighborhood is Cumberland Gardens, a seven-story building for low-income senior citizens that opened in 2001, sponsored by the New York Foundation for Senior Citizens. As the architect commented, "The building’s facade recalls traditional New York City apartment buildings and complements the surrounding row houses."

Final changes

This January, according to a 1/21/06 article in the Brooklyn Papers headlined 35 years later, Fort Greene to be ‘renewed’, Community Board 2 approved the last project in ATURA. The Fifth Avenue Committee will build 80 condos on Atlantic Avenue between South Portland and South Oxford streets, just east of the Atlantic Center mall.

This January, according to a 1/21/06 article in the Brooklyn Papers headlined 35 years later, Fort Greene to be ‘renewed’, Community Board 2 approved the last project in ATURA. The Fifth Avenue Committee will build 80 condos on Atlantic Avenue between South Portland and South Oxford streets, just east of the Atlantic Center mall.

The article stated:

I asked Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee why the building is ten stories rather than taller. "As a long-time community development corporation with strong ties to the communities we serve, we strive to build buildings that are in keeping with the character of the surrounding neighborhood," she wrote, adding, "Ten stories is sufficient for us to meet our affordability goals for the site and is in keeping with height of other surrounding buildings. We did have to seek a zoning waiver to go to the ten-story height."

I asked Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee why the building is ten stories rather than taller. "As a long-time community development corporation with strong ties to the communities we serve, we strive to build buildings that are in keeping with the character of the surrounding neighborhood," she wrote, adding, "Ten stories is sufficient for us to meet our affordability goals for the site and is in keeping with height of other surrounding buildings. We did have to seek a zoning waiver to go to the ten-story height."

Note that the row houses nearby are three stories, and the 1970s subsidized coops are up to 15 stories. The senior housing a few blocks away is seven stories, while the Atlantic Center mall next door has three levels. Keep in mind, however, that the mall may be torn down for a high-rise development, and the Atlantic Yards plan would include much taller buildings.

A geographer comments

Was it all worth it? “[T]he designation of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area may have done more to accelerate the decline of Fort Greene than to arrest and reverse it. The site was cleared and then left abandoned for close to 30 years, while attempts by the city to develop it failed to come to fruition,” writes Winifred Curran of the DePaul University Department of Geography, in an article published in 1998 (City Policy and Urban Renewal: A Case Study of Fort Greene Brooklyn; Middle States Geographer).

But the past decade marked changes. “This trend was finally reversed in the 1990s….” comments Curran, formerly of Hunter College in New York. “While what was built represents a compromise of sorts, the poor design and ill-considered nature of the developments pose a threat to the unique character of this brownstone neighborhood.” While Curran doesn't break down all the costs and benefits, she observes, “The city has spent an extraordinary amount of money to attract development that might have occurred anyway.” For example, by 1992, the city had spent $166 million in capital improvements to facilitate development.

So the story behind the failure to develop the railyard raises questions about whether an emphasis on process over projects might have been more fruitful.

Development ups and downs

Markowitz said that the “Atlantic Yards area has been available for any developer”? Well, maybe the Vanderbilt Yard, but not the area, especially if you consider the ups and downs of parcels nearby. The Daily News built a printing plant on Dean Street in 1927. In 1983, as the Times reported in an 11/27/83 article headlined “The Intricacies of Initiating Development Projects,” city officials helped the newspaper add parking space and a new 15,000-square-foot warehouse, despite complaints from neighbors.

Markowitz said that the “Atlantic Yards area has been available for any developer”? Well, maybe the Vanderbilt Yard, but not the area, especially if you consider the ups and downs of parcels nearby. The Daily News built a printing plant on Dean Street in 1927. In 1983, as the Times reported in an 11/27/83 article headlined “The Intricacies of Initiating Development Projects,” city officials helped the newspaper add parking space and a new 15,000-square-foot warehouse, despite complaints from neighbors.

The plant closed, however, at the end of 1996, as the newspaper moved its printing operations to a more modern facility in New Jersey. The building was a haven for squatters for several years, and a friend tells me he inquired and was told it could be purchased for $1.3 million. (That's not a typo.) Then developer Shaya Boymelgreen bought the building and converted it into the luxury Newswalk condominium complex, which opened in 2002. The block it occupies was sliced out of the Atlantic Yards site plan. As the Village Voice noted in a 4/5/04 article, “But if Ratner could design around Newswalk, he could have spared other properties as well.” In other words, development is always in flux.

A valuable plot nearby

A block east of the Atlantic Center mall, on South Oxford Street just past the Atlantic Commons development, a 4,000 square foot mansion and associated properties has been sold for $13 million. According to the New York Daily News, the owner will keep the mansion but demolish two carriage houses and a two-family home to build a 40,000 square foot luxury high-rise building on the property. How big would that be? In the ballpark of The Greene House a few blocks away, at least.

A block east of the Atlantic Center mall, on South Oxford Street just past the Atlantic Commons development, a 4,000 square foot mansion and associated properties has been sold for $13 million. According to the New York Daily News, the owner will keep the mansion but demolish two carriage houses and a two-family home to build a 40,000 square foot luxury high-rise building on the property. How big would that be? In the ballpark of The Greene House a few blocks away, at least.

Preservationists are concerned about keeping the mansion, which falls outside the boundaries of the current Fort Greene Historic District, though there are efforts to expand that district. The bucolic mansion likely will be joined by a mid-sized tower, maybe ten to 12 stories. If the Atlantic Yards project proceeds at current projections, towers some 40 stories tall would be built nearby, just down the block and across Atlantic Avenue.

ATURA almost forgotten

The term “Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area” has fallen out of favor. Though it has been cited recently in the Brooklyn press, such as this Brooklyn Papers article, a Lexis-Nexis search shows that it was last used in the city’s daily newspapers nearly eight years ago, in a 3/27/98 New York Times article headlined “Plan Ratified for Mall at L.I.R.R. Terminal.” The term “Atlantic Terminal area” is more common, such as in a 2/19/06 Times article headlined “Coming Soon, 9 Million Stories in the Crowded City,” which cited “proposed development, including… the Atlantic Terminal area in Brooklyn.” The Empire State Development Corporation's Draft Scope of Analysis for an Environmental Impact Statement locates the Atlantic Yards project "in the Atlantic Terminal area of Brooklyn."

Two weeks ago, Bertha Lewis, executive director of New York ACORN, at a panel on affordable housing, pronounced, "For 30 years, the yards sat.”

She's right, but the story behind it can't be summed up in a soundbite.

Charles Gargano, chairman of the Empire State Development Corporation, mused on 11/15/05 to WNYC's Brian Lehrer, “Isn’t it interesting that these railyards have sat for decades and decades and decades, and no one has done a thing about them.” Forest City Ratner spokesman Joe DePlasco, in a 12/19/04 New York Times article ("In a War of Words, One Has the Power to Wound") described the railyards as "an empty scar dividing the community."

But why exactly has the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard never been developed? Do public officials have some responsibility?

But why exactly has the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard never been developed? Do public officials have some responsibility?At a hearing yesterday of the Brooklyn Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee, Kate Suisman, aide to Council Member Letitia James, honed in on the question. The topic was land use, and Winston Von Engel, Deputy Director of the Department of City Planning's Brooklyn office, was on the hot seat in the Borough Hall courtroom. (Photo from Dope on the Slope.)

"Just to be clear, this was a project that was initiated by the developer--is that right?" asked Suisman, whose boss is the leading public official opposed to Forest City Ratner's project.

"That's our understanding," Von Engel replied. (Well, Markowitz approached developer Bruce Ratner with the idea of bringing a basketball team to Brooklyn, and the developer recognized that a standalone arena wouldn't make economic sense.)

"Had the city been looking at making use of the land?" Suisman pressed on politely.

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said. He noted that there were once plans decades ago for a campus for Baruch College of the City University of New York, as part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). "This area was looked at in a very large context. What survived was the Atlantic Center mall [pictured], the Atlantic Terminal mall, the housing. So, in that sense there were plans at one point, but some of them were not realized."

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said. He noted that there were once plans decades ago for a campus for Baruch College of the City University of New York, as part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA). "This area was looked at in a very large context. What survived was the Atlantic Center mall [pictured], the Atlantic Terminal mall, the housing. So, in that sense there were plans at one point, but some of them were not realized."He cited a recent rezoning for the Newswalk building--condos built out of an old Daily News manufacturing plant that sits on a piece of land sliced out of the Atlantic Yards footprint--and noted that other property owners in Prospect Heights had begun to convert industrial buildings to residential ones.

Suisman continued: Was there a reason the city didn't take a look at the area?

"We didn't decide to take a look at the yards," Von Engel replied. "They belong to the Long Island Rail Road. They use them heavily. They're critical to their operations. You do things in a step-by-step process. We concentrated on the Downtown Brooklyn development plan for Downtown Brooklyn. Forest City Ratner owns property across the way. And they saw the yards, and looked at those. We had not been considering the yards directly."

At the head of the table, Markowitz looked a bit pained, as a woman young enough to be his daughter educed the city's diffidence in developing the site. There were fewer than ten people in the audience, and maybe a dozen public officials, aides, and community board representatives around the table. It was another episode in the Atlantic Yards Committee's curious mix of impotence and importance.

Was there ever an RFP? Remember, Andrew Alper, president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, told City Council at a 5/4/04 hearing: So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and try to find a better deal.

The importance of context

Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards proposal must be seen in context with other nearby projects, many of which did not come into fruition until the past decade, after the area rebounded economically. The blocks around the railyards--the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--have been in various stages of decline, clearance, and renewal. As the photo at right (updated: taken sometime after the 1988 demolition of the Flatbush Terminal and before the mid-90s construction on urban renewal land) suggests, large lots of land north of Atlantic Avenue (the northern border of the railyards) were scars themselves, decades after urban renewal began. The urban renewal land had to become scarce enough for a developer to target the railyards, which require a platform for construction. (Also, the railyard function must be moved nearby.)

Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards proposal must be seen in context with other nearby projects, many of which did not come into fruition until the past decade, after the area rebounded economically. The blocks around the railyards--the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--have been in various stages of decline, clearance, and renewal. As the photo at right (updated: taken sometime after the 1988 demolition of the Flatbush Terminal and before the mid-90s construction on urban renewal land) suggests, large lots of land north of Atlantic Avenue (the northern border of the railyards) were scars themselves, decades after urban renewal began. The urban renewal land had to become scarce enough for a developer to target the railyards, which require a platform for construction. (Also, the railyard function must be moved nearby.) The photo at right, picturing mid-2005 conditions, was taken after the openings of the Atlantic Center mall (1996) and the Atlantic Terminal mall (2004). (Photos from Forest City Ratner presentation to City Council on 5/26/05.)

The photo at right, picturing mid-2005 conditions, was taken after the openings of the Atlantic Center mall (1996) and the Atlantic Terminal mall (2004). (Photos from Forest City Ratner presentation to City Council on 5/26/05.)The city’s clearance of substandard housing and relocation of the Fort Greene Meat Market led—eventually--to major changes. More than two decades before the malls, the major construction in the ATURA consisted of six subsidized apartment buildings, five up to 15 stories high, and one that's 31 stories high. In the mid-1990s, as the first mall was being constructed, different kinds of subsidized housing--numerous row houses--were constructed, and later a seven-story building for senior citizens was built. (The photo is taken from the Sixth Avenue bridge, over the railyards, approaching Atlantic Avenue and looking northeast.)

Over the years, though, more ambitious projects fell by the wayside, including a development with new office towers, a possible sports arena, and a new campus for Baruch College of City University of New York, to be built over the railyards.

Over the years, though, more ambitious projects fell by the wayside, including a development with new office towers, a possible sports arena, and a new campus for Baruch College of City University of New York, to be built over the railyards.A good part of the problem was money. A city plan to move Baruch College to a parcel that included the railyards was stalled in 1973, as the city lacked $27 million (some $120 million in March 2006 dollars) to build a platform for new construction. Last year, the MTA estimated the cost of a platform and a new yard at $56-$72 million, though bidders Extell and Forest City Ratner estimated higher costs.

Nearby, new homeowners invested in row-house blocks; the Fort Greene Historic District was designated in 1978. The president of the Downtown Brooklyn Development Association as saying the brownstoners helped usher in business and government investment, according to a 6/9/77 article in the Brooklyn Phoenix quoted by geographer Winifred Curran in her analysis of ATURA (see below). Some neighborhood residents also resisted major development projects, fearing congestion and crime. Echoes of the Atlantic Yards controversy? Partly--but the scale of the new plan is far larger.

ATURA boundaries

More than half of the Atlantic Yards footprint, including the railyard, would fall within the boundaries of ATURA, a more than 40-year-old experiment in urban planning. The 104-acre site (originally 85 acres) is located mostly in Fort Greene, including the sites that became the Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center malls north of Atlantic Avenue, plus a variety of subsidized housing, including high-rises and row houses.

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street (but not the buildings on the south side of the street).

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street (but not the buildings on the south side of the street). ATURA includes the segments of the Atlantic Yards plan between Pacific and Atlantic: the railyards and the two plots of land to the west, which Site 6-A, the triangle of land between Fifth, Atlantic, and Flatbush Avenues, and Site 5, now occupied by P.C. Richard/Modell's, and a community garden. The latter two were originally in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, but were excised because they overlapped with the Atlantic Yards plan. They are arguably the only segments of the Atlantic Yards plan that are in Downtown Brooklyn--unless the concept of downtown is extended. (Site 5, which is south of Flatbush Avenue, might be said to be in Park Slope, while Site 6-A might be said to be in Prospect Heights.)

ATURA includes the segments of the Atlantic Yards plan between Pacific and Atlantic: the railyards and the two plots of land to the west, which Site 6-A, the triangle of land between Fifth, Atlantic, and Flatbush Avenues, and Site 5, now occupied by P.C. Richard/Modell's, and a community garden. The latter two were originally in the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, but were excised because they overlapped with the Atlantic Yards plan. They are arguably the only segments of the Atlantic Yards plan that are in Downtown Brooklyn--unless the concept of downtown is extended. (Site 5, which is south of Flatbush Avenue, might be said to be in Park Slope, while Site 6-A might be said to be in Prospect Heights.)Dodger hopes

Brooklyn went into decline in the 1950s, as suburbs drew people and businesses, and government agencies let banks redline neighborhoods to stymie investment. Even before ATURA, some big plans were floated. In early 1954, according to Michael Shapiro’s book “The Last Good Season,” the president of the New York Council of Wholesale Meat Dealers wrote to Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, asking for help in relocating the “vast and fetid Fort Greene Meat Market,” which was deteriorating rapidly.

Brooklyn went into decline in the 1950s, as suburbs drew people and businesses, and government agencies let banks redline neighborhoods to stymie investment. Even before ATURA, some big plans were floated. In early 1954, according to Michael Shapiro’s book “The Last Good Season,” the president of the New York Council of Wholesale Meat Dealers wrote to Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, asking for help in relocating the “vast and fetid Fort Greene Meat Market,” which was deteriorating rapidly.The location “sat above the Brooklyn terminus of the Long Island Rail Road,” Shapiro wrote. (Actually, it was to the east nearby.) It represented a solution for Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, whose Ebbets Field in the Flatbush neighborhood was small and antiquated, with limited access to parking and public transit. (Photo from Brooklyn Eagle via Brooklyn Public Library.)

“It was impossible to envision a better site for a new Brooklyn ballpark,” Shapiro wrote, channeling Cashmore’s observations. Robert Moses, the city’s planning czar, however, wanted a new stadium at Flushing Meadows, near a highway and accessible to suburbanites—which he eventually got.

“It was impossible to envision a better site for a new Brooklyn ballpark,” Shapiro wrote, channeling Cashmore’s observations. Robert Moses, the city’s planning czar, however, wanted a new stadium at Flushing Meadows, near a highway and accessible to suburbanites—which he eventually got.Moses, according to Shapiro, opposed Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley’s desire to use public money or governmental condemnation powers to build the stadium at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. Roger Kahn, in his book, “The Era,” added that Moses thought there would be too much traffic at the site—an issue that recurs today. (Photo of the crossroads of Flatbush and Atlantic, looking southeast, in 1947, from the Brooklyn Public Library's Brooklyn Eagle collection. The roof of the Long Island Rail Road station is in the lower left. That is now the site of the Atlantic Terminal mall.)

ATURA emerges

In 1962, according to a 9/5/65 New York Times article, “the City Planning Commission recommended a sweeping $150 million redevelopment and rehabilitation program for the area surrounding the Long Island terminal at Atlantic Avenue.” (By the way, $150 million in 1962 dollars would be nearly $1 billion in March 2006 dollars.) “Known as the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, the plan included the removal of the Fort Greene Meat Market, an antiquated wholesale market behind the terminal, the clearance of slums and the construction of low-income and middle income apartment houses and industrial buildings."

That 1965 New York Times article, headlined “Vacant Store Windows Stare At Once-Bustling Flatbush Ave.,” painted a grim picture, citing 43 empty storefronts between DeKalb Avenue and Grand Army Plaza. A city spokesman said—presciently, it turns out—“that it would be ‘literally years’ before any physical change would be made.” A local businessman—again presciently—wondered why the area was in decline. “We’ve got everything in the way of transportation here,” said Frederick Kriete, assistant vice-president of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. “It’s a little Times Square.”

For another history of ATURA, see this animated timeline produced by the Center for Urban Pedagogy. I can't confirm all the facts/dates, but much is consonant with the information below.

Baruch mentions

By 1968, there were inklings of change, with redevelopment to be anchored by education. The Times reported, in a 4/17/68 article headlined “Sale of L.I.U. Site Opposed by Mayor,” that, according to one CUNY source, Mayor John Lindsay supported a new site for Manhattan’s Baruch College “within a triangular-shaped area bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, in the Crown Heights section.” Though the exact location was not specified, the site, south of Atlantic Avenue, would apparently have included the railyards. (Crown Heights? Apparently not everyone was calling it Prospect Heights.)

By 1968, there were inklings of change, with redevelopment to be anchored by education. The Times reported, in a 4/17/68 article headlined “Sale of L.I.U. Site Opposed by Mayor,” that, according to one CUNY source, Mayor John Lindsay supported a new site for Manhattan’s Baruch College “within a triangular-shaped area bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, in the Crown Heights section.” Though the exact location was not specified, the site, south of Atlantic Avenue, would apparently have included the railyards. (Crown Heights? Apparently not everyone was calling it Prospect Heights.)A 6/24/68 Times article, headlined “Renewal Raises Brooklyn Hopes,” described the city’s urban renewal plan as $250 million (over $1.4 billion in March 2006 dollars). It portrayed some serious blight:

The pavement smells of rancid fat on a warm day and the meat cutting continues through the night. The plants are surrounded by residential houses.

Three blocks of open railroad tracks alongside Atlantic Avenue and an abandoned railroad loading platform, where vagrants, addicts and drunks sleep and prostitutes congregate even during the day.

Houses that in the words of Borough President Abe Stark are ‘unfit for human habitation.'

The renewal plan, according to the Times, “calls for 2,400 new low- and middle-income housing units to replace 800 dilapidated units, removal of the blighting Fort Greene Meat Market, a 14-acre site for the City University’s new Baruch College, two new parks and community facilities such as day-care centers.”

Meat market moves

The meat market lingered. On 10/24/68, the Times reported, the city had decided to move the market to an area between the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges, which has since become the upscale neighborhood known as DUMBO. Otis Pratt Pearsall of the Municipal Art Society called it “an outrageous misuse of a prime section of river frontage.” On 2/8/69, the Times reported, five Brooklyn Heights homeowners, supported by the Brooklyn Heights Association, sued to block the move, saying that the site—defunct Civil War-era warehouses-—should be developed into housing and recreation.

Some six months later, on 8/19/69, the Times reported that the city had chosen a site in Sunset Park, apparently responding to the criticism. But the move came slowly. In early 1975, the Times was predicting a move that spring; on 7/14/76, the Times reported that the market remained unfinished because the builder was in default.

Subsidized housing plans

While the subsidized housing didn't arrive until 1976, plans emerged years before that. A 9/23/70 article in the Times described plans to build a 300-unit public housing project on a 2.2-acre between Carlton Avenue and Adelphi Street and between Atlantic Avenue in Fulton Street, near the eastern end of ATURA. It was initially described as a 20-story building, but it ultimately became Atlantic Terminal Site 4B, a 31-story building and the tallest city housing project, built just north of Atlantic Avenue between Clermont and Carlton Avenues.

While the subsidized housing didn't arrive until 1976, plans emerged years before that. A 9/23/70 article in the Times described plans to build a 300-unit public housing project on a 2.2-acre between Carlton Avenue and Adelphi Street and between Atlantic Avenue in Fulton Street, near the eastern end of ATURA. It was initially described as a 20-story building, but it ultimately became Atlantic Terminal Site 4B, a 31-story building and the tallest city housing project, built just north of Atlantic Avenue between Clermont and Carlton Avenues.A 10/31/71 article, headlined “Rebuilding To Start at L.I.R. Area in Brooklyn,” cited plans to begin that building “next spring,” and plans to building 2,400 housing units “and a $97 million new home for Baruch College to straddle Atlantic Avenue.” (That’s $475 million in March 2006 dollars.) The college buildings “would be built on air rights over the Long Island’s underground train shed and underground storage yards.” Along Flatbush Avenue, the area “has become so blighted that a commuters’ bar near the station keeps its door locked at night and customers are admitted only after scrutiny by the bartender.” Meanwhile, construction had been scheduled for a replacement meat market located in Sunset Park—not the area that would become DUMBO—though it would take years to complete.

In late 1972, the City Planning Commission approved plans to construct five moderate-income buildings. "Although some elected officials are urging caution and review, I say six years of study, planning and review have already gone by and this project must be approved now," the former chairman of Community Board 2, Roy Vanasco, told the Times (Planners Approve 2 Projects in Brooklyn, 12/17/72).

A 1/27/73 article in the Times, headlined “Housing is Voted for Fort Greene,” described plans to construct those five buildings. Two of them, 12 and 15 stories high, would be “in the middle of the block bounded by Hanson Place, North Portland Avenue, Atlantic Avenue and South Elliott Place.” These (right) are the Atlantic Terminal I coops, a 15-story building on South Portland Avenue and a 12-story building on South Elliott Place. These are just north of the southeast segment of the Atlantic Center mall. (The mall lacks entrances near those towers; blame fear of local youths and others. In the background is the Bank of New York tower on top of the Atlantic Terminal mall, built in 2004.)

A 1/27/73 article in the Times, headlined “Housing is Voted for Fort Greene,” described plans to construct those five buildings. Two of them, 12 and 15 stories high, would be “in the middle of the block bounded by Hanson Place, North Portland Avenue, Atlantic Avenue and South Elliott Place.” These (right) are the Atlantic Terminal I coops, a 15-story building on South Portland Avenue and a 12-story building on South Elliott Place. These are just north of the southeast segment of the Atlantic Center mall. (The mall lacks entrances near those towers; blame fear of local youths and others. In the background is the Bank of New York tower on top of the Atlantic Terminal mall, built in 2004.)The second project, Atlantic Terminal II, was to consist of three buildings, 9, 13, and 15 stories high, near the Atlantic Terminal 4B building. Ultimately, the project, on Carlton Avenue and Fulton Street, included one 15-story coop and two 13-story buildings, known as Atlantic Terminal II. They are Mitchell-Lama buildings.

The site clearance required significant urban renewal. In a 6/17/73 article headlined “Brooklyn Renewal Slowly Advances,” the Times noted that the city had acquired 461 buildings, demolishing most of them, and had 200 more buildings slated for condemnation. Some 375 businesses and 750 families had been moved, with another 75 businesses and 165 families slated to move.

The site clearance required significant urban renewal. In a 6/17/73 article headlined “Brooklyn Renewal Slowly Advances,” the Times noted that the city had acquired 461 buildings, demolishing most of them, and had 200 more buildings slated for condemnation. Some 375 businesses and 750 families had been moved, with another 75 businesses and 165 families slated to move.Arena hopes

That 1/27/73 article reported that Brooklyn Borough President Sebastian Leone “urged the rebuilding of the Long Island Rail Road terminal at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues and the construction of a new hotel, a sports arena and other facilities in the area.”

More than a year later, in a 7/17/74 article, Leone was reported to promote his idea before the New York State Sports Authority. The article, headlined “Arena Plan Is Pressed in Brooklyn,” noted that community opponents preferred low income housing and expressed fears of traffic jams and air pollution.

Residents even sued to block a proposed $50,000 feasibility study of a 15,000 seat arena, according to a 2/23/75 article headlined "Brooklyn Arena Study Halted." But when the suit was withdrawn, lawyers representing the city and state said the study wouldn't proceed anyhow, since the state's Sport Authority was expected to be abolished. The suit was to represent homeowners from Bensonhurst, Bay Ridge, Coney Island, and the Atlantic Terminal area. Leone said he didn't think the oft-mentioned Atlantic Terminal area was in fact the best location. "And anyway," he told the newspaper, "we have plans for housing there." A representative of a Fort Greene group fighting the arena supported "additional middle-income cooperative housing."

The possibility of an arena occasionally revived. A 6/6/84 article in the Times, headlined, “Site Near Shea Favored For Domed Stadium,” cited discussions about a new arena “in the Atlantic Terminal area of Brooklyn, at the site of Aqueduct Race Track in Queens, or near Shea Stadium.”

Ultimately, as an 8/25/91 Newsday article reported, proponents of the Brooklyn Sportsplex, as the 1990s version of the project was known, decided to push for an indoor arena and outdoor stadium in Coney Island. “There were just too many people who didn’t want it there,” said Robert Zeig of the Brooklyn Sports Foundation, referring to an arena in ATURA.

A new Baruch site, and fiscal crisis

Meanwhile, Baruch’s plans were on hold, as a CUNY spokesman said in the 1/27/73 article that the Board of Higher Education decided to keep the college in Manhattan “after learning it would cost $27 million just to build a platform of the Long Island Rail Road tracks on which to construct the college.”

But there was more space in ATURA. In 12/4/73 article in the Times, headlined “Beame Is Said to Favor the ‘Concept’ Of Moving Baruch College to Brooklyn,” Borough President Leone said that, because the originally proposed site posed an engineering difficulty, Baruch would then be offered a different site, covering 10 acres.

A year later, in a 12/18/74 article headlined “Baruch College Will Be Moved To $73 Million Site in Brooklyn,” the Times reported that the college would move to a 15-acre site north of the railyards, bounded by Atlantic Avenue, Fulton Street, Carlton Avenue, South Oxford Street and South Portland Avenue. The scheduled completion date was 1980. While the exact dimensions are unclear, that is roughly the area east of (but perhaps including part of) the Atlantic Center mall—an area later slated for subsidized low-rise housing.

A 1/16/75 article, headlined “New Campus in Brooklyn Wins Support,” pointed out that the project would “probably halve the 2,400 moderate income housing units planned.” Speakers at a City Planning Commission hearing “expressed concern that additional units might be sacrificed for a proposed Brooklyn sports arena.”

Six weeks later, a 3/2/75 article about the City Planning Commission, headlined “Do-It-Yourself Plan For Garage Killed,” offered slightly different boundaries for the Baruch plan: Atlantic Avenue, Fulton Street, Carlton Avenue, Hanson Place, and Flatbush Avenue.”

The project seemed to be moving ahead. A 3/7/75 article, headlined “Board of Estimate Votes Tunnel-Work Compromise,” reported that the Board of Estimate, then a crucial layer in city government, approved street closings and zoning changes for the Baruch campus, after agreeing to reserve an adjacent parcel for additional low- and moderate-income housing. A 3/19/75 Times article ("New Baruch College Site Approved") reported that the city's Site Selection Board signed off on the location, but city and state budget officials still needed to approve the plans before architects could get to work.

Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable surveyed the plans for Baruch and commercial redevelopment, and citing ongoing neighborhood renewal in a 3/30/75 article buoyantly headlined "The Blooming of Downtown Brooklyn."

Not so fast. The Baruch move became a casualty of the city’s fiscal crisis. (That famous New York Daily News headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” ran on 10/30/75.) A 3/18/77 article in the Times, “Atlantic Avenue to Bloom Anew In a Brooklyn Restorer’s Plan,” pointed out that work in ATURA had stalled. “But the city’s financial plight has set back hopes for a new Baruch College campus in the City University system, financial problems have delayed the move of the Fort Greene meat market, and prospects for new housing at present are dim.”

Not so fast. The Baruch move became a casualty of the city’s fiscal crisis. (That famous New York Daily News headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” ran on 10/30/75.) A 3/18/77 article in the Times, “Atlantic Avenue to Bloom Anew In a Brooklyn Restorer’s Plan,” pointed out that work in ATURA had stalled. “But the city’s financial plight has set back hopes for a new Baruch College campus in the City University system, financial problems have delayed the move of the Fort Greene meat market, and prospects for new housing at present are dim.”80s ambitions

By the 1980s, plans grew more ambitious. A 6/1/84 Times article headlined, “Brooklyn Uplift: Hotel Reborn as Apartment House,” described changes around the Brooklyn Academy of Music in Fort Greene. It noted how “the main governmental interest now is the development of new office space on urban renewal tracts to create ‘back office’ white collar jobs.”

This was because Jersey City had begun to attract jobs from Manhattan--which was countered, ultimately, by Forest City Ratner's MetroTech development downtown. “For example, a long block to the south of the academy, at the Brooklyn terminus of the Long Island Rail Road, is an immense undeveloped track in the Atlantic Terminal urban renewal area. There is potential for 1 million to 1.5 million square feet of office space and 700 to 1,000 housing units there.”

Meanwhile, smaller-scale development proceeded. A development of 13 3.5-story buildings, including 98 units, was planned as infill housing on Fulton Street, Gates Avenue, and Adelphi Street “along the perimeter of the still largely undeveloped Atlantic Terminal urban renewal area,” according to a 11/9/84 article in the Times headlined “Brownstone Look Returning in Fort Greene Project.” The article pointed out that the buildings required city and federal subsidies: “As with much land in the city’s inventory, values in the neighborhood are not strong enough to generate speculative construction.”

It should be noted that the Fort Greene Historic District had been established in 1978; the counterpart in adjacent Clinton Hill was established in 1981. Owners of buildings in historic districts get a tax break for fixing up their buildings and must get permission to change the look of those buildings; the designation generally serves as a rising tide for property values. Now, speculative construction is common.

1985: big plans emerge

In early 1985, according to a 1/17/85 Times article headlined “Office-Housing Plan for Downtown Brooklyn,” Mayor Ed Koch and business leaders announced a $255 million office/retail/housing complex in ATURA. (That would be $470 million in March 2006 dollars.) The article pointed out that ATURA “was declared an urban renewal zone in 1968 but has never had any major construction, has been singled out by the city as a site for back-office space for Manhattan businesses.”

The project would create 1,680 jobs and have two phases. The first phase, over 18 acres, would include 600,000 square feet of office space, 400 housing units—geared at low and middle-income people—a movie theater, and a supermarket. The second phase would include 1.2 million square feet of office space. When the developer, Rose Associates, completed the second stage, it could develop an additional 1.2 million square feet of office and retail space nearby.