Would the Atlantic Yards project bring $6 billion in new revenue to the city and state over 30 years?

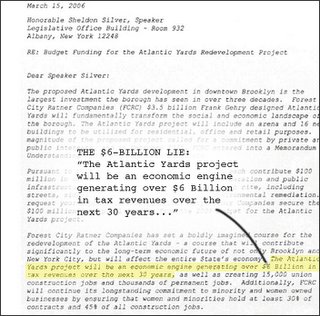

Would the Atlantic Yards project bring $6 billion in new revenue to the city and state over 30 years? That's developer Forest City Ratner's mantra, in meetings, in the Brooklyn Standard promotional sheet, and now in a letter (right) they're providing to state legislators in an effort to lobby Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver.

The state budget is supposed to be decided by April 1, and the developer seeks the inclusion of $100 million in state aid promised in a 2005 Memorandum of Understanding, even though the project is still in the early stages of review.

The $6 billion is the biggest lie in the whole Atlantic Yards controversy.

OK, syntactically, it's not a lie. The $6 billion has indeed been estimated in a study FCR commissioned, written by sports economist Andrew Zimbalist. But it's not credible. It results from manipulated statistics, an enormous (and methodologically flawed) overestimate of revenues, and an omission (and then an underestimate) of costs.

The study's conclusions--and FCR's manipulation of them--are challenged in reports by two city agencies and two outside analysts, not to mention an application of some economic common sense.

Here are some glaring flaws in the FCR-paid study. It ignores the cost of traffic and transportation improvements. It claims a new arena wouldn't increase police costs and lowballs other public costs.

Here are some glaring flaws in the FCR-paid study. It ignores the cost of traffic and transportation improvements. It claims a new arena wouldn't increase police costs and lowballs other public costs.

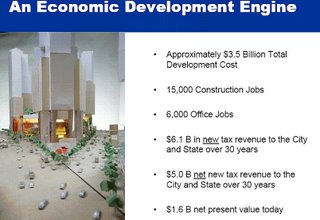

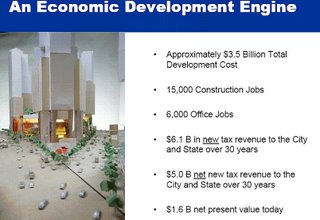

And, in claiming financial benefits, it relies on the dubious theory that building new luxury housing will bring new income tax revenue to New York. If so, any new luxury housing development in the city should be considered an "economic development engine," which is how FCR described the project (above) to City Council last May. (Note that FCR also fudges claims about construction jobs, and the number of office jobs promised has been cut by more than half since the City Council presentation.)

So here are 15 reasons to question the purported $6 billion.

1) The source is the developer's paid consultant.

Andrew Zimbalist's report, Estimated Fiscal Impact of the Atlantic Yards Project on the New York City and New York State Treasuries, was issued in May 2004 and updated in June 2005. (See p. 35 of the updated report.) Any report funded by a developer should be questioned, and tested against reports from government agencies and outside critics. No outside analyst has endorsed Zimbalist's conclusions; in fact, the September 2005 Independent Budget Office (IBO) Fiscal Brief declined to estimate revenues from the non-arena portion of the project, citing "methodological limitations."

FCR VP Jim Stuckey claimed at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing: It is really not our report, it is Professor Zimbalist’s report. But Stuckey’s statement is undermined by Zimbalist’s 2004 acknowledgement that he relied on information supplied by the developer: Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for FCRC. I have discussed these estimates with FCRC and they seem reasonable to me.

FCR VP Jim Stuckey claimed at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing: It is really not our report, it is Professor Zimbalist’s report. But Stuckey’s statement is undermined by Zimbalist’s 2004 acknowledgement that he relied on information supplied by the developer: Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for FCRC. I have discussed these estimates with FCRC and they seem reasonable to me.

Curiously, the acknowledgement in Zimbalist's 2005 update substitutes "Nets" for "Forest City Ratner Companies": Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for the Nets. I have discussed these estimates with the Nets and they seem reasonable to me.

The Nets, however, are not responsible for the project construction--the team is owned by a group with numerous owners who are not part of Forest City Ratner. The change reads like a fig leaf to distance the economist from his patron.

And Zimbalist, who teaches at Smith College in Northampton, MA, hasn't been forthcoming. In their June 2004 critique of Zimbalist's first report, urban planner Jung Kim and anthropologist Gustav Peebles--both of whom have backgrounds in economics--write: Much of Dr. Zimbalist’s data is culled from biased or unsubstantiated sources, including data from consulting firms hired by FCRC or from FCRC itself, as Dr. Zimbalist himself admits throughout the paper. We contacted him several times in order to try to get precise citations for the numbers he produces, but all our efforts were in vain.

2) Zimbalist was working outside of his expertise.

2) Zimbalist was working outside of his expertise.

A 2004 FCR flier refers to "respected Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist." Stuckey told City Council that we retained Professor Zimbalist because we wanted somebody who historically [has] been against doing arenas and stadium[s]. While Zimbalist has a long history of analyzing the fiscal impact of sports facilities, he has no such track record in analyzing broader urban development projects like this one, which concerns not just an arena, but also 16 mostly residential towers. (Zimbalist's long list of consultant jobs refers almost exclusively to sports, though one vaguely cites a “new civic center.”)

Zimbalist offers no indication that asked any other economists for feedback. By contrast, Kim and Peebles, who critiqued Zimbalist's study, did test their conclusions with outside economists.

Referring to Zimbalist's study, "I would never have undertaken this exercise,” Washington State University sports economist Rod Fort told Neil deMause, a journalist specializing in the impact of sports facilities. “In essence, Andy is trying to forecast 33 years hence, and he’s forecasting housing markets, which there are other people spending all their waking moments on. What you see is assumption after assumption after assumption after assumption.”

3) The $6 billion estimate does not incorporate the costs of the project.

3) The $6 billion estimate does not incorporate the costs of the project.

Zimbalist estimates those 30-year costs at $1.1 billion, as FCR's Stuckey told (right) City Council last May. (Project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn estimate nearly $2 billion--a figure that deserves further discussion.)

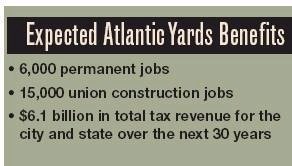

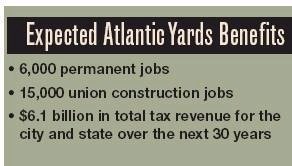

Notably, a front-page article in the first issue (June 2005) of FCR's Brooklyn Standard promotional sheet said (below): "Expected to generate $6.1 billion over the next 30 years for the city and state...."

Notably, a front-page article in the first issue (June 2005) of FCR's Brooklyn Standard promotional sheet said (below): "Expected to generate $6.1 billion over the next 30 years for the city and state...."

An FAQ in the second issue (October 2005), on page 5, stated, "The project is expected to generate over $6 billion in new tax revenues for New York City and State over the next 30 years....." Neither of those passages mentioned the costs.

In an affidavit in the recent court case regarding FCR's effort to demolish five properties it owns, FCR's Stuckey did acknowledge the costs: "We also estimate that the Project will generate $6.1 billion in new tax revenues-and $5.0 billion in net tax revenues - for the City and the State over the next 30 years."

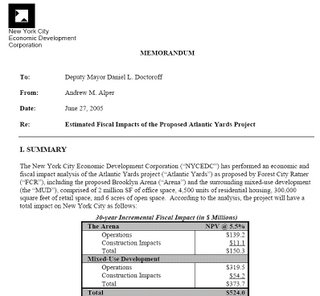

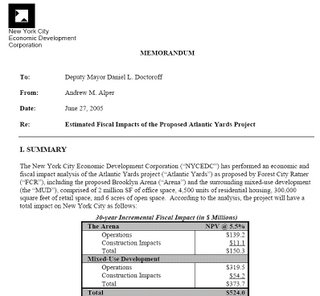

As noted, the governmental studies of fiscal impact have major flaws. A New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) analysis, dated June 2005 but likely completed months earlier, does not estimate any costs for the project, just revenues. And the IBO report ignores revenues from the considerable non-arena portion of the product. The critique of Zimbalist's first report, by Kim and Peebles, does try to assess the full costs and benefits, and estimates that the taxpayers could lose up to $500 million on the project over 30 years.

An 11/27/05 New York Times editorial attempted to draw a conclusion about the whole project, but failed because it was based on the incomplete IBO report: The Nets arena is not destined to be a cash cow, but the borough deserves a sports team, so long as the price is not too high.

4) Forest City Ratner manipulates statistics.

There are two ways to look at the revenues and costs: the 30-year aggregate or the figure in current dollars, known as net present value. (The aggregate is always significantly larger, since it incorporates interest and other capital costs.) The IBO report and the NYCEDC analysis use present value, as that is the standard for such economic evaluations. Zimbalist mainly uses present value; in the concluding section of his 2004 report, he provides the aggregate as alternative, but in the conclusion of the 2005 update, he leaves out the aggregate.

Forest City Ratner, however, typically ignores the standard and publicizes the 30-year aggregate. Why? Likely because the number is larger and accentuates the ratio between benefits and costs. For benefits, the 30-year total would be $6.1 billion, with a present value of $2.1 billion. For costs, the 30-year total would be $1.1 billion, with a present value of $572.6 million. Thus, the use of the aggregate also exaggerates the ratio between benefits and costs--from 6-to-1 rather than 4-to-1. (However, as noted below, neither set of numbers is reliable.)

5) Zimbalist's report makes a fundamental methodological error.

In its March 2005 analysis, "Slam Dunk or Air Ball?," the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development (PICCED) notes that the FCR-sponsored report, and as well as the Kim-Peebles critique, should not have treated housing as a contributor to economic development, because the new taxes paid by residents could also be counted in other economic development plans, such as job-retention efforts. The PICCED report states:

Zimbalist concludes [in his first report, in May 2004] that the FCRC project, after covering publicly-borne capital and operating costs, will produce a net benefit to the City and State treasuries of $812.7 million (present value terms). However, by far, the largest source of projected revenues ($896.6 million, or 57.9% of the total of $1.5 billion in present value revenues), is in personal income and sales taxes based on the incomes of the new residents of the housing component. Without these housing-related tax flows, Zimbalist’s estimates show that the balance of the FCRC project is a money-loser to the City and State treasuries, i.e., the only way the FCRC proposal overall makes fiscal sense is by including tax revenues from the housing component.

Major Flaw in Both Studies

These two studies share a major methodological flaw in that they both count the positive fiscal effect of the income of the residents who will occupy the 4500-unit residential development. While the two studies make different assumptions about the likely income of new residents, (Zimbalist assumes an average income of $80,000; Kim and Peebles assume and average of $50,000 to $60,000) both give the overall project credit for the income of new residents, and for the local and state tax revenues that such incomes would generate.

This is a very problematic assumption, tantamount to assuming that residents bring their own jobs to the City when they move in to a new housing unit. While residents who are new to the City will add to the City’s labor supply, unless they are self- employed, they do not “create” their own jobs. If the City started to give housing projects “credit” for the creation of jobs held by their residents, a double counting problem would result since the city routinely gives businesses “credit” for expanding employment or relocating jobs to NYC and this then often enters into the fiscal “score-keeping” for economic development projects receiving City (and State) subsidies.

(Emphasis added.)

I asked James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute, who worked on the Pratt report, if there was any precedent for Zimbalist's methodology. He responded, "I don't know of any serious cost-benefit analyses of mixed-used economic development projects that count the taxes of residents. That's why we said it was a methodological flaw."

The IBO, as noted, did not analyze the non-arena portion of the plan, citing "the methodological limitations in estimating the fiscal impacts of mixed-use developments."

In his most recent report, Zimbalist estimates (p. 36) $2.1 billion in present value tax revenues and $6 billion in aggregate tax revenues. Nearly half of those new revenues would be attributed to residential income taxes.

6) Even if you accept the "methodological flaw," Zimbalist's assumptions are wrong.

The NYCEDC also estimates revenue from new residents, but uses different statistics, which would significantly lower tax revenues. As I've noted, Zimbalist, in his first report, projects that the average annual income of households in the development would be between $80,000 and $90,000. In his second report, in 2005, he projects that the average annual income would be $94,875. (If he were to do another report, acknowledging the addition of another 1,300 market-rate condos, his estimate undoubtedly would rise.)

But the city economic development agency says you can't count new Atlantic Yards residents as new taxpayers. Rather, the agency assumes that the new units "will represent an equivalent increase in households Citywide, either directly in the project itself or as infill in units vacated by households relocating to the project. Income tax revenue is based on an average income of $45,000, the Citywide average for all industries." Obviously, people earning $45,000 pay less in taxes than those earning more than $90,000, and revenues based on new city residents would be lower.

A comparison of Zimbalist's 2004 report and its 2005 update points out the fallacy of using new residents to estimate economic impact. His initial report estimates a 30-year aggregate of $4.1 billion in new revenue and about $1.3 billion in costs. His update, as noted above, estimates $6.1 billion in revenue and $1.1 billion in costs. The major contributor to this magical 50 percent leap in revenue: more well-off new residents. Based on this rationale, the city should subsidize high-end housing and recruit rich taxpayers. Except the city is now doing the opposite: cutting back on tax breaks for market-rate development.

7) Zimbalist overstates the market for office space.

7) Zimbalist overstates the market for office space.

In his May 2004 report, he writes that the project would eventually create 1.9 million square feet of first-class office space. He makes no mention of a study of Downtown Brooklyn redevelopment issued a month earlier, which estimates a glut of office space in the area just west of the Atlantic Yards footprint. He cites a "housing and commercial office space shortage in Brooklyn and New York City" and offers some questionable statistics: Since 1988, downtown Brooklyn has absorbed an average of 600,000 square feet of new office space per year. As of early April 2004, the vacancy rate of class A office space built in Brooklyn since 1985 was less than one percent.

In their June 2004 critique, Gustav Peebles and Jung Kim point out that Zimbalist fails to calculate a vacancy rate for the new Atlantic Yards office space, and that his observation regarding the Brooklyn vacancy rate requires a huge caveat. Most of the Class A office space in Brooklyn is at Forest City Ratner's MetroTech development, which has relied heavily on subsidies and government tenants to fill the space. (The NYCEDC more soberly calculates a 7% vacancy rate.)

Zimbalist, in his June 2005 updated report, acknowledges changes in FCR's plans that would create either 1.2 million or 259,078 square feet square feet of first-class office space. But he repeats the same decontextualized citations of a low vacancy rate and downtown Brooklyn's capacity to absorb office space even though Forest City Ratner had itself reacted to the market by proposing cuts of 43% to 88% from the originally announced space. Nor does he acknowledge any competing supply of office space from either the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning or from Lower Manhattan.

8) Zimbalist underestimates public safety costs.

Incredibly, Zimbalist doesn't assume additional costs for police coverage of a sports arena and a new development with some 15,000 residents. He writes: Based on conversations with former budget officials, FCRC concludes that the increment in fire and police budgets would be negligible.

Zimbalist doesn't even put that conclusion in his own words--does he believe it? Anyone who has attended a professional sports event knows that additional security is needed for crowd control and public safety. The arena also would be used for other large gatherings, and it would be adjacent to a major transit hub. It would also require monitoring as a potential terrorist target--which would also increase costs.

The IBO, surprisingly, leans toward Zimbalist regarding fire protection, saying that the additional costs "would be relatively low." (The agency, however, doesn't use the term "negligible.") However, the IBO disagrees with Zimbalist on costs for police, asserting that "costs to the city for policing the new Nets arena could be significant."

9) Zimbalist underestimates other public costs.

The IBO tried to estimate some public costs posed by the project as a whole, concluding that new education, sanitation, and police services over 30 years would be $530 million in present value. That's 65 percent more ($208.6 million) more than the $321.4 million estimated by Zimbalist. Such a wide divergence is no rounding error; it's a cry for greater scrutiny of the numbers.

Note that the public costs almost certainly would be even higher, since more housing would be built. The IBO's higher cost prediction was based on an estimated 6,000 housing units, not the 5,850 number used by Zimbalist. However, the developer now plans at least 7,300 units onsite, plus up to 1,000 additional units offsite. More people require more city services.

10) Zimbalist's report ignores significant costs for traffic, transportation, and parking improvements.

So do the other analyses by the IBO, and NYCEDC. Community Consulting estimated a $4 billion cost over nearly a decade for traffic, parking, and transit improvements in the Downtown Brooklyn area at large. Traffic engineer Brian Ketcham of Community Consulting, examining the initial configuration of the Atlantic Yards project, estimated the social costs of traffic alone at $76 million a year, with more than half of that coming from congestion. (The document isn't online.)

Architect Jonathan Cohn points out: If those who are calling for an arena at any cost really cared about doing it right, there would have been a study of a range of possible sites, with pros and cons identified and analyzed.

The Pratt report observes:

The developer has thus far provided no meaningful information on traffic impacts or mitigation plans. Traffic congestion in downtown Brooklyn is already severe and will grow worse in years to come as development in Downtown Brooklyn proceeds (following a recent rezoning). If substantial parts of Brooklyn can expect severe traffic gridlock on a regular basis because of the project, it could be a “no-go” regardless of other benefits. If the project does go forward, FCRC and the City should use this opportunity to engage in “big picture” thinking about Brooklyn’s transit infrastructure – not only traffic calming but also potential light rail, waterfront linkages, and ticket discounts for taking public transit. In any case, the public costs (and ancillary benefits) for mitigating potential traffic impacts from the project should be factored into the fiscal analysis of the project. (Emphasis added.)

11) Zimbalist overestimates the number of workers associated with the Nets who would pay city income taxes.

11) Zimbalist overestimates the number of workers associated with the Nets who would pay city income taxes.

As noted in Chapter 3 of my report, Zimbalist assumes that 30 percent of the Nets players would live in the five boroughs and pay city and state taxes, while 75 percent of the arena workers would live in the city. However, NYCEDC estimates that 20 percent of the players, 35 percent of the executives and team staff, and 50 percent of the facility staff would reside in New York City. NYCEDC bases its estimates on "figures from other area professional sports teams." Zimbalist gets his estimates from Forest City Ratner.

12) There are unexplained inconsistencies between Zimbalist's two reports.

For example, in his first report, Zimbalist estimates that new income-tax revenues based on Nets players who relocated to New York City or State would be $4.88 million in 2008. In his update, he adjusts that figure to $7.47 million for 2009--a more than 50 percent jump in one year. He estimates similar leaps in income-tax revenues between 2008 and 2009 from Nets executives, staff, and arena workers. In his first report, he assumes arena-worker salaries would total $7.06 million. In his update, he assumes those salaries would total $16.4 million--more than double.

Similarly, in his first report, he estimates that new sales-tax revenue from the arena would be $6.43 million in 2008. In his update, he estimates $9.62 million in revenue for 2009--a nearly 50 percent leap.

In his first report, Zimbalist writes (p. 18), "I also assume that 10 percent of the workforce from among the Atlantic Yards households will work outside of New York City and, hence, not be responsible for paying New York City income taxes." In his update, the Massachusetts-based academic drops that assumption without offering an explanation: he apparently learned that New York City residents must pay city income tax no matter where they work.

13) Zimbalist overestimates the potential for revenues from the Brooklyn arena.

His 2005 report states: The Nets project that the arena will not host an NHL team and that it will host 226 events during the year (assuming the eventual closing of CAA, no new arena in Newark, no NHL and no minor league hockey events at the Atlantic Yards arena).

(Emphasis added; also note that his earlier report, in 2004, instead quotes the developer: "FCRC projects... 224 events.")

By contrast, NYCEDC forecasts a total of 192 events each year at the arena. NYCEDC forecasts an average attendance of 9,476 at events other than NBA basketball games; Zimbalist does not try to estimate the attendance at such events. As for competition, a new arena in Newark is already under construction and would compete for events.

14) Zimbalist's estimate of the number of current Nets fans who would attend games is questionable.

The Nets arena is estimated to offer a relatively small positive fiscal impact, and the revenue is dependent, in part, on retaining current Nets fans from New Jersey. Neil deMause, a journalist specializing in analysis of sports facilities, critiqued the IBO study, which, like Zimbalist's analysis, uses FCR estimates regarding the arena:

First of all, the IBO's conclusions result primarily from assumptions of how many current Nets fans would accompany the team from Jersey to Brooklyn, bringing their sales tax dollars with them - assumptions that, according to the IBO report, were provided by Ratner himself. Ratner's figures assume that "about half of those attending Nets games at the Atlantic Yards arena will be from the ranks of those attending now" - a debatable assumption given that it's quite a shlep from New Jersey to Brooklyn, not to mention that the proposed arena would hold 18,000 fans, and the Nets currently average fewer than 15,000 fans per game. Tweak the assumptions to have only 30% of Nets attendance represent new spending instead of 50%, and the arena would be a net loss.

15) Zimbalist's numbers are out of date.

His updated report assesses plans that would build either 6000 or 6800 dwelling units. Now Forest City Ratner plans 7300 units at the Atlantic Yards site, plus another 6000 to 1000 affordable condos, either onsite or offsite (more likely offsite). An increase in housing, by Zimbalist's lights, would lead to more revenues, and it also would lead to more costs. Still, the project is expected to shrink, as architect Frank Gehry said in January. Either way, all the fiscal reports are stale.

The year of magical thinking

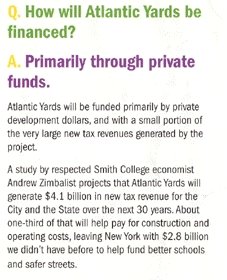

A 2004 FCR flier sent to Brooklynites contained this passage:

A 2004 FCR flier sent to Brooklynites contained this passage:

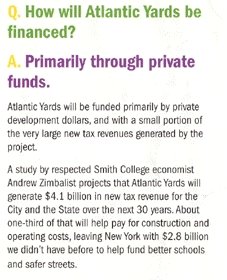

Q. How will Atlantic Yards be financed?

A. Primarily through private funds.

…A study by respected Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist projects that Atlantic Yards will generate $4.1 billion in new tax revenue for the City and the State over the next 30 years. About one-third of that will help pay for construction and operating costs, leaving New York with $2.8 billion we didn’t have before to help fund better schools and safer streets.

A year later, the developer was predicting $6 billion in new tax revenue, a magical 50 percent leap, mainly from the increase in high-end residential units.

Does adding more market-rate housing really provide an economic boost to the city and state? Would the Atlantic Yards project really help fund better schools and safer streets, or would it be a fiscal drain?

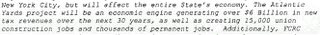

We can't be certain, and the studies by government agencies have been inadequate. But we know that $6 billion claim is enormously overstated. It is a 30-year aggregate figure based on a tower of assumptions. It does not include public costs for such services as extra police for arena events and traffic amelioration around the project. It improperly relies on revenues from new residents. (FCR in the excerpt above sent to legislators also fudges claims about jobs.)

We can't be certain, and the studies by government agencies have been inadequate. But we know that $6 billion claim is enormously overstated. It is a 30-year aggregate figure based on a tower of assumptions. It does not include public costs for such services as extra police for arena events and traffic amelioration around the project. It improperly relies on revenues from new residents. (FCR in the excerpt above sent to legislators also fudges claims about jobs.)

Whether it is FCR’s report or "Professor Zimbalist’s report," as Stuckey told the City Council, it is not a sound academic exercise. Rather, it's a tool in a deceptive public relations strategy.

The $6 billion is the biggest lie in the whole Atlantic Yards controversy.

OK, syntactically, it's not a lie. The $6 billion has indeed been estimated in a study FCR commissioned, written by sports economist Andrew Zimbalist. But it's not credible. It results from manipulated statistics, an enormous (and methodologically flawed) overestimate of revenues, and an omission (and then an underestimate) of costs.

The study's conclusions--and FCR's manipulation of them--are challenged in reports by two city agencies and two outside analysts, not to mention an application of some economic common sense.

Here are some glaring flaws in the FCR-paid study. It ignores the cost of traffic and transportation improvements. It claims a new arena wouldn't increase police costs and lowballs other public costs.

Here are some glaring flaws in the FCR-paid study. It ignores the cost of traffic and transportation improvements. It claims a new arena wouldn't increase police costs and lowballs other public costs.And, in claiming financial benefits, it relies on the dubious theory that building new luxury housing will bring new income tax revenue to New York. If so, any new luxury housing development in the city should be considered an "economic development engine," which is how FCR described the project (above) to City Council last May. (Note that FCR also fudges claims about construction jobs, and the number of office jobs promised has been cut by more than half since the City Council presentation.)

So here are 15 reasons to question the purported $6 billion.

1) The source is the developer's paid consultant.

Andrew Zimbalist's report, Estimated Fiscal Impact of the Atlantic Yards Project on the New York City and New York State Treasuries, was issued in May 2004 and updated in June 2005. (See p. 35 of the updated report.) Any report funded by a developer should be questioned, and tested against reports from government agencies and outside critics. No outside analyst has endorsed Zimbalist's conclusions; in fact, the September 2005 Independent Budget Office (IBO) Fiscal Brief declined to estimate revenues from the non-arena portion of the project, citing "methodological limitations."

FCR VP Jim Stuckey claimed at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing: It is really not our report, it is Professor Zimbalist’s report. But Stuckey’s statement is undermined by Zimbalist’s 2004 acknowledgement that he relied on information supplied by the developer: Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for FCRC. I have discussed these estimates with FCRC and they seem reasonable to me.

FCR VP Jim Stuckey claimed at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing: It is really not our report, it is Professor Zimbalist’s report. But Stuckey’s statement is undermined by Zimbalist’s 2004 acknowledgement that he relied on information supplied by the developer: Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for FCRC. I have discussed these estimates with FCRC and they seem reasonable to me.Curiously, the acknowledgement in Zimbalist's 2005 update substitutes "Nets" for "Forest City Ratner Companies": Many of the numbers used in this report concerning Nets attendance, ticket prices, construction costs and other items come from projections done by or for the Nets. I have discussed these estimates with the Nets and they seem reasonable to me.

The Nets, however, are not responsible for the project construction--the team is owned by a group with numerous owners who are not part of Forest City Ratner. The change reads like a fig leaf to distance the economist from his patron.

And Zimbalist, who teaches at Smith College in Northampton, MA, hasn't been forthcoming. In their June 2004 critique of Zimbalist's first report, urban planner Jung Kim and anthropologist Gustav Peebles--both of whom have backgrounds in economics--write: Much of Dr. Zimbalist’s data is culled from biased or unsubstantiated sources, including data from consulting firms hired by FCRC or from FCRC itself, as Dr. Zimbalist himself admits throughout the paper. We contacted him several times in order to try to get precise citations for the numbers he produces, but all our efforts were in vain.

2) Zimbalist was working outside of his expertise.

2) Zimbalist was working outside of his expertise.A 2004 FCR flier refers to "respected Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist." Stuckey told City Council that we retained Professor Zimbalist because we wanted somebody who historically [has] been against doing arenas and stadium[s]. While Zimbalist has a long history of analyzing the fiscal impact of sports facilities, he has no such track record in analyzing broader urban development projects like this one, which concerns not just an arena, but also 16 mostly residential towers. (Zimbalist's long list of consultant jobs refers almost exclusively to sports, though one vaguely cites a “new civic center.”)

Zimbalist offers no indication that asked any other economists for feedback. By contrast, Kim and Peebles, who critiqued Zimbalist's study, did test their conclusions with outside economists.

Referring to Zimbalist's study, "I would never have undertaken this exercise,” Washington State University sports economist Rod Fort told Neil deMause, a journalist specializing in the impact of sports facilities. “In essence, Andy is trying to forecast 33 years hence, and he’s forecasting housing markets, which there are other people spending all their waking moments on. What you see is assumption after assumption after assumption after assumption.”

3) The $6 billion estimate does not incorporate the costs of the project.

3) The $6 billion estimate does not incorporate the costs of the project.Zimbalist estimates those 30-year costs at $1.1 billion, as FCR's Stuckey told (right) City Council last May. (Project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn estimate nearly $2 billion--a figure that deserves further discussion.)

Notably, a front-page article in the first issue (June 2005) of FCR's Brooklyn Standard promotional sheet said (below): "Expected to generate $6.1 billion over the next 30 years for the city and state...."

Notably, a front-page article in the first issue (June 2005) of FCR's Brooklyn Standard promotional sheet said (below): "Expected to generate $6.1 billion over the next 30 years for the city and state...." An FAQ in the second issue (October 2005), on page 5, stated, "The project is expected to generate over $6 billion in new tax revenues for New York City and State over the next 30 years....." Neither of those passages mentioned the costs.

In an affidavit in the recent court case regarding FCR's effort to demolish five properties it owns, FCR's Stuckey did acknowledge the costs: "We also estimate that the Project will generate $6.1 billion in new tax revenues-and $5.0 billion in net tax revenues - for the City and the State over the next 30 years."

As noted, the governmental studies of fiscal impact have major flaws. A New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) analysis, dated June 2005 but likely completed months earlier, does not estimate any costs for the project, just revenues. And the IBO report ignores revenues from the considerable non-arena portion of the product. The critique of Zimbalist's first report, by Kim and Peebles, does try to assess the full costs and benefits, and estimates that the taxpayers could lose up to $500 million on the project over 30 years.

An 11/27/05 New York Times editorial attempted to draw a conclusion about the whole project, but failed because it was based on the incomplete IBO report: The Nets arena is not destined to be a cash cow, but the borough deserves a sports team, so long as the price is not too high.

4) Forest City Ratner manipulates statistics.

There are two ways to look at the revenues and costs: the 30-year aggregate or the figure in current dollars, known as net present value. (The aggregate is always significantly larger, since it incorporates interest and other capital costs.) The IBO report and the NYCEDC analysis use present value, as that is the standard for such economic evaluations. Zimbalist mainly uses present value; in the concluding section of his 2004 report, he provides the aggregate as alternative, but in the conclusion of the 2005 update, he leaves out the aggregate.

Forest City Ratner, however, typically ignores the standard and publicizes the 30-year aggregate. Why? Likely because the number is larger and accentuates the ratio between benefits and costs. For benefits, the 30-year total would be $6.1 billion, with a present value of $2.1 billion. For costs, the 30-year total would be $1.1 billion, with a present value of $572.6 million. Thus, the use of the aggregate also exaggerates the ratio between benefits and costs--from 6-to-1 rather than 4-to-1. (However, as noted below, neither set of numbers is reliable.)

5) Zimbalist's report makes a fundamental methodological error.

In its March 2005 analysis, "Slam Dunk or Air Ball?," the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development (PICCED) notes that the FCR-sponsored report, and as well as the Kim-Peebles critique, should not have treated housing as a contributor to economic development, because the new taxes paid by residents could also be counted in other economic development plans, such as job-retention efforts. The PICCED report states:

Zimbalist concludes [in his first report, in May 2004] that the FCRC project, after covering publicly-borne capital and operating costs, will produce a net benefit to the City and State treasuries of $812.7 million (present value terms). However, by far, the largest source of projected revenues ($896.6 million, or 57.9% of the total of $1.5 billion in present value revenues), is in personal income and sales taxes based on the incomes of the new residents of the housing component. Without these housing-related tax flows, Zimbalist’s estimates show that the balance of the FCRC project is a money-loser to the City and State treasuries, i.e., the only way the FCRC proposal overall makes fiscal sense is by including tax revenues from the housing component.

Major Flaw in Both Studies

These two studies share a major methodological flaw in that they both count the positive fiscal effect of the income of the residents who will occupy the 4500-unit residential development. While the two studies make different assumptions about the likely income of new residents, (Zimbalist assumes an average income of $80,000; Kim and Peebles assume and average of $50,000 to $60,000) both give the overall project credit for the income of new residents, and for the local and state tax revenues that such incomes would generate.

This is a very problematic assumption, tantamount to assuming that residents bring their own jobs to the City when they move in to a new housing unit. While residents who are new to the City will add to the City’s labor supply, unless they are self- employed, they do not “create” their own jobs. If the City started to give housing projects “credit” for the creation of jobs held by their residents, a double counting problem would result since the city routinely gives businesses “credit” for expanding employment or relocating jobs to NYC and this then often enters into the fiscal “score-keeping” for economic development projects receiving City (and State) subsidies.

(Emphasis added.)

I asked James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute, who worked on the Pratt report, if there was any precedent for Zimbalist's methodology. He responded, "I don't know of any serious cost-benefit analyses of mixed-used economic development projects that count the taxes of residents. That's why we said it was a methodological flaw."

The IBO, as noted, did not analyze the non-arena portion of the plan, citing "the methodological limitations in estimating the fiscal impacts of mixed-use developments."

In his most recent report, Zimbalist estimates (p. 36) $2.1 billion in present value tax revenues and $6 billion in aggregate tax revenues. Nearly half of those new revenues would be attributed to residential income taxes.

6) Even if you accept the "methodological flaw," Zimbalist's assumptions are wrong.

The NYCEDC also estimates revenue from new residents, but uses different statistics, which would significantly lower tax revenues. As I've noted, Zimbalist, in his first report, projects that the average annual income of households in the development would be between $80,000 and $90,000. In his second report, in 2005, he projects that the average annual income would be $94,875. (If he were to do another report, acknowledging the addition of another 1,300 market-rate condos, his estimate undoubtedly would rise.)

But the city economic development agency says you can't count new Atlantic Yards residents as new taxpayers. Rather, the agency assumes that the new units "will represent an equivalent increase in households Citywide, either directly in the project itself or as infill in units vacated by households relocating to the project. Income tax revenue is based on an average income of $45,000, the Citywide average for all industries." Obviously, people earning $45,000 pay less in taxes than those earning more than $90,000, and revenues based on new city residents would be lower.

A comparison of Zimbalist's 2004 report and its 2005 update points out the fallacy of using new residents to estimate economic impact. His initial report estimates a 30-year aggregate of $4.1 billion in new revenue and about $1.3 billion in costs. His update, as noted above, estimates $6.1 billion in revenue and $1.1 billion in costs. The major contributor to this magical 50 percent leap in revenue: more well-off new residents. Based on this rationale, the city should subsidize high-end housing and recruit rich taxpayers. Except the city is now doing the opposite: cutting back on tax breaks for market-rate development.

7) Zimbalist overstates the market for office space.

7) Zimbalist overstates the market for office space.In his May 2004 report, he writes that the project would eventually create 1.9 million square feet of first-class office space. He makes no mention of a study of Downtown Brooklyn redevelopment issued a month earlier, which estimates a glut of office space in the area just west of the Atlantic Yards footprint. He cites a "housing and commercial office space shortage in Brooklyn and New York City" and offers some questionable statistics: Since 1988, downtown Brooklyn has absorbed an average of 600,000 square feet of new office space per year. As of early April 2004, the vacancy rate of class A office space built in Brooklyn since 1985 was less than one percent.

In their June 2004 critique, Gustav Peebles and Jung Kim point out that Zimbalist fails to calculate a vacancy rate for the new Atlantic Yards office space, and that his observation regarding the Brooklyn vacancy rate requires a huge caveat. Most of the Class A office space in Brooklyn is at Forest City Ratner's MetroTech development, which has relied heavily on subsidies and government tenants to fill the space. (The NYCEDC more soberly calculates a 7% vacancy rate.)

Zimbalist, in his June 2005 updated report, acknowledges changes in FCR's plans that would create either 1.2 million or 259,078 square feet square feet of first-class office space. But he repeats the same decontextualized citations of a low vacancy rate and downtown Brooklyn's capacity to absorb office space even though Forest City Ratner had itself reacted to the market by proposing cuts of 43% to 88% from the originally announced space. Nor does he acknowledge any competing supply of office space from either the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning or from Lower Manhattan.

8) Zimbalist underestimates public safety costs.

Incredibly, Zimbalist doesn't assume additional costs for police coverage of a sports arena and a new development with some 15,000 residents. He writes: Based on conversations with former budget officials, FCRC concludes that the increment in fire and police budgets would be negligible.

Zimbalist doesn't even put that conclusion in his own words--does he believe it? Anyone who has attended a professional sports event knows that additional security is needed for crowd control and public safety. The arena also would be used for other large gatherings, and it would be adjacent to a major transit hub. It would also require monitoring as a potential terrorist target--which would also increase costs.

The IBO, surprisingly, leans toward Zimbalist regarding fire protection, saying that the additional costs "would be relatively low." (The agency, however, doesn't use the term "negligible.") However, the IBO disagrees with Zimbalist on costs for police, asserting that "costs to the city for policing the new Nets arena could be significant."

9) Zimbalist underestimates other public costs.

The IBO tried to estimate some public costs posed by the project as a whole, concluding that new education, sanitation, and police services over 30 years would be $530 million in present value. That's 65 percent more ($208.6 million) more than the $321.4 million estimated by Zimbalist. Such a wide divergence is no rounding error; it's a cry for greater scrutiny of the numbers.

Note that the public costs almost certainly would be even higher, since more housing would be built. The IBO's higher cost prediction was based on an estimated 6,000 housing units, not the 5,850 number used by Zimbalist. However, the developer now plans at least 7,300 units onsite, plus up to 1,000 additional units offsite. More people require more city services.

10) Zimbalist's report ignores significant costs for traffic, transportation, and parking improvements.

So do the other analyses by the IBO, and NYCEDC. Community Consulting estimated a $4 billion cost over nearly a decade for traffic, parking, and transit improvements in the Downtown Brooklyn area at large. Traffic engineer Brian Ketcham of Community Consulting, examining the initial configuration of the Atlantic Yards project, estimated the social costs of traffic alone at $76 million a year, with more than half of that coming from congestion. (The document isn't online.)

Architect Jonathan Cohn points out: If those who are calling for an arena at any cost really cared about doing it right, there would have been a study of a range of possible sites, with pros and cons identified and analyzed.

The Pratt report observes:

The developer has thus far provided no meaningful information on traffic impacts or mitigation plans. Traffic congestion in downtown Brooklyn is already severe and will grow worse in years to come as development in Downtown Brooklyn proceeds (following a recent rezoning). If substantial parts of Brooklyn can expect severe traffic gridlock on a regular basis because of the project, it could be a “no-go” regardless of other benefits. If the project does go forward, FCRC and the City should use this opportunity to engage in “big picture” thinking about Brooklyn’s transit infrastructure – not only traffic calming but also potential light rail, waterfront linkages, and ticket discounts for taking public transit. In any case, the public costs (and ancillary benefits) for mitigating potential traffic impacts from the project should be factored into the fiscal analysis of the project. (Emphasis added.)

11) Zimbalist overestimates the number of workers associated with the Nets who would pay city income taxes.

11) Zimbalist overestimates the number of workers associated with the Nets who would pay city income taxes. As noted in Chapter 3 of my report, Zimbalist assumes that 30 percent of the Nets players would live in the five boroughs and pay city and state taxes, while 75 percent of the arena workers would live in the city. However, NYCEDC estimates that 20 percent of the players, 35 percent of the executives and team staff, and 50 percent of the facility staff would reside in New York City. NYCEDC bases its estimates on "figures from other area professional sports teams." Zimbalist gets his estimates from Forest City Ratner.

12) There are unexplained inconsistencies between Zimbalist's two reports.

For example, in his first report, Zimbalist estimates that new income-tax revenues based on Nets players who relocated to New York City or State would be $4.88 million in 2008. In his update, he adjusts that figure to $7.47 million for 2009--a more than 50 percent jump in one year. He estimates similar leaps in income-tax revenues between 2008 and 2009 from Nets executives, staff, and arena workers. In his first report, he assumes arena-worker salaries would total $7.06 million. In his update, he assumes those salaries would total $16.4 million--more than double.

Similarly, in his first report, he estimates that new sales-tax revenue from the arena would be $6.43 million in 2008. In his update, he estimates $9.62 million in revenue for 2009--a nearly 50 percent leap.

In his first report, Zimbalist writes (p. 18), "I also assume that 10 percent of the workforce from among the Atlantic Yards households will work outside of New York City and, hence, not be responsible for paying New York City income taxes." In his update, the Massachusetts-based academic drops that assumption without offering an explanation: he apparently learned that New York City residents must pay city income tax no matter where they work.

13) Zimbalist overestimates the potential for revenues from the Brooklyn arena.

His 2005 report states: The Nets project that the arena will not host an NHL team and that it will host 226 events during the year (assuming the eventual closing of CAA, no new arena in Newark, no NHL and no minor league hockey events at the Atlantic Yards arena).

(Emphasis added; also note that his earlier report, in 2004, instead quotes the developer: "FCRC projects... 224 events.")

By contrast, NYCEDC forecasts a total of 192 events each year at the arena. NYCEDC forecasts an average attendance of 9,476 at events other than NBA basketball games; Zimbalist does not try to estimate the attendance at such events. As for competition, a new arena in Newark is already under construction and would compete for events.

14) Zimbalist's estimate of the number of current Nets fans who would attend games is questionable.

The Nets arena is estimated to offer a relatively small positive fiscal impact, and the revenue is dependent, in part, on retaining current Nets fans from New Jersey. Neil deMause, a journalist specializing in analysis of sports facilities, critiqued the IBO study, which, like Zimbalist's analysis, uses FCR estimates regarding the arena:

First of all, the IBO's conclusions result primarily from assumptions of how many current Nets fans would accompany the team from Jersey to Brooklyn, bringing their sales tax dollars with them - assumptions that, according to the IBO report, were provided by Ratner himself. Ratner's figures assume that "about half of those attending Nets games at the Atlantic Yards arena will be from the ranks of those attending now" - a debatable assumption given that it's quite a shlep from New Jersey to Brooklyn, not to mention that the proposed arena would hold 18,000 fans, and the Nets currently average fewer than 15,000 fans per game. Tweak the assumptions to have only 30% of Nets attendance represent new spending instead of 50%, and the arena would be a net loss.

15) Zimbalist's numbers are out of date.

His updated report assesses plans that would build either 6000 or 6800 dwelling units. Now Forest City Ratner plans 7300 units at the Atlantic Yards site, plus another 6000 to 1000 affordable condos, either onsite or offsite (more likely offsite). An increase in housing, by Zimbalist's lights, would lead to more revenues, and it also would lead to more costs. Still, the project is expected to shrink, as architect Frank Gehry said in January. Either way, all the fiscal reports are stale.

The year of magical thinking

A 2004 FCR flier sent to Brooklynites contained this passage:

A 2004 FCR flier sent to Brooklynites contained this passage:Q. How will Atlantic Yards be financed?

A. Primarily through private funds.

…A study by respected Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist projects that Atlantic Yards will generate $4.1 billion in new tax revenue for the City and the State over the next 30 years. About one-third of that will help pay for construction and operating costs, leaving New York with $2.8 billion we didn’t have before to help fund better schools and safer streets.

A year later, the developer was predicting $6 billion in new tax revenue, a magical 50 percent leap, mainly from the increase in high-end residential units.

Does adding more market-rate housing really provide an economic boost to the city and state? Would the Atlantic Yards project really help fund better schools and safer streets, or would it be a fiscal drain?

Whether it is FCR’s report or "Professor Zimbalist’s report," as Stuckey told the City Council, it is not a sound academic exercise. Rather, it's a tool in a deceptive public relations strategy.

Comments

Post a Comment