|

| Lewis/PBS NewsHour |

But the page is the Housing Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) Lewis signed last May, which guaranteed that half the 4500 rental units in the project would be affordable, and also said that developer Forest City Ratner (FCR) would aim to build up to 1000 affordable for-sale units. However, FCR has since added 2800 market-rate condos, so even if all 1000 for-sale units were built, the 8300-unit project would include only about 40 percent affordable units.

Nope, says Lewis. “If this project passes [state review], it’s 50/50 baby,” she told a group of reporters pressing her after a panel last night. “The MOU says 50/50 period.”

Actually, the MOU leaves some breathing room: If the projected number of residential units should increase for any reason that the Developer determines to be economically necessary, both the Developer and ACORN will work towards developing a program that follows the same guidelines and principles set forth in this document.

(Indeed, the number increased, just a week after the MOU for the rentals was celebrated last May 19.)

Charged discussion

|

| Lander/POV on PBS |

It was a charged end to a tense night in a clubby banquet room at The Captain’s Ketch, a restaurant in the Wall Street area. A few dozen members of Women in Housing and Finance paid $30 last night for appetizers, wine, and a chance to hear a panel discussion titled Affordable Housing and the Atlantic Yards Development.

They got their money’s worth. Moderator Brad Lander, director of the Pratt Center for Community Development announced at the start that he wanted “to set a space for respectful dialogue,” but that didn’t last long.

Lewis was initially eloquent, but as the event continued, her fuse got shorter, and she interrupted Lander and co-panelist Candace Carponter of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) with regular protests and counter-arguments.

It left an uneasy feeling that the Atlantic Yards debate will get uglier, and that the clash will persist between ACORN and fellow “equity advocates” (in Lander’s words) with DDDB and fellow “livability advocates.” It left Michelle de la Uz, who runs a nonprofit housing group that has criticized the project, to say that neither value should be sacrificed.

And it left panelist Vicky Been, a New York University law professor who spoke in careful generalities about Atlantic Yards, to lament that “the system is broken” because “we don’t have a comprehensive approach to planning.” Been also pointed out, almost as an aside, that we still don’t know how much the project would cost the public.

After Lander described the contours and changes in the affordable housing element of the Atlantic Yards project, Lewis offered the big picture.

ACORN in 1997 did a study called “Shrinking the Pie,” which showed how the Giuliani administration shifted affordable housing funds to higher-income people.

A 2003 study, Neighborhoods for Sale, showed “how city policies were selling off whole neighborhoods.” The acceptable affordable housing program for developers, she said, was the city's 80/20 program, which she said was inadequate.

“There’s almost 49 developments in Downtown Brooklyn and surrounding areas,” Lewis said, and most are luxury condos in a skyrocketing market. “There’s a total of 5219 housing units,” she said. “Ninety-one percent are market rate. Nine percent are ‘affordable,’ that a working family can’t afford, a teacher, a bus driver.”

(This week's New York Observer has an article about how tax breaks have stimulated developments that would succeed on their own, and how the Bloomberg administration is finally reshaping the program.)

So ACORN, she said, negotiated with Bruce Ratner and said, “We want half. We developed this 50/50 program. They don’t know anything about affordable housing.... We stretched the program that HPD does.... It doesn't make sense, so we changed it.”

Yes, ACORN successfully stretched the program to lower the income cap and increase the income categories (or tiers) of people eligible. But HPD calls it a 50/30/20 program, with 20 percent of the units for low-income families and 30 percent for middle- and moderate-income people.

Lewis continued, “The apartment sizes--there’s no affordable housing program, except for ours, that actually does two- and three-bedrooms.” Not so, said de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee afterwards, and a quick check of the HPD web site confirms that.

“The for-sale housing, you will see, will have the same tiers,” Lewis said. “The tiers will start a bit higher.” How high is unclear. The MOU states: Developer and ACORN will work on a program to develop affordable for-sale units,which are intended to be in the range of 600 to 1000 units, over the course of ten (10) years and can be on or off site.It is currently contemplated that a majority of the affordable for-sale units will be sold to families in the upper affordable income tiers.

DDDB's response

After Lewis’s passionate performance, Carponter was on the defensive somewhat, since she had to argue larger issues of fairness. "I don’t know as much about affordable housing," she acknowledged, "but I do know about the plan.... We want development in this space, but we want sensible, responsible development that meets community needs."

However, she added, "The baby got thrown out with the bathwater. In order to get the affordable housing, we've lost our sense of community and ability to have input into the public process."

She cited some statistics that quickly had Lewis fuming--it would cost at least three times as much to build this as other organizations could do it, it would use eminent domain, and $1.5 to $2 billion to build the project. (Forest City Ratner's Jim Stuckey acknowledges $1.1 billion.)

She cited some statistics that quickly had Lewis fuming--it would cost at least three times as much to build this as other organizations could do it, it would use eminent domain, and $1.5 to $2 billion to build the project. (Forest City Ratner's Jim Stuckey acknowledges $1.1 billion.)

“This is a low-rise neighborhood,” Carponter said, adding, “Most of the buildings are five or six stories. It’s Brownstone Brooklyn at its organic best.”

Well, much of surrounding Prospect Heights has developed organically, but only one block in the footprint is defined by row houses and another contains two classy condo renovations. Other blocks are either empty (the railyards) or have more buildings or lots awaiting redevelopment.

“Of the number of residential units, only 30% are going to be affordable housing,” Carponter said. Well, 30% of the onsite units. If Forest City Ratner follows through and builds all 1,000 for-sale affordable units, that would bring the project to 40%--the number Lewis was loathe to acknowledge. Carponter added, "The promise of affordable purchase units has not been met."

“The affordable housing, the promise of jobs are being used as a Trojan horse for a massive land grab,” she said. “It is not necessary to build an arena to build affordable housing.” She said that the Fifth Avenue Committee and Pratt Area Community Council could build affordable housing at a third of the costs the Atlantic Yards project would require.

“It’s taking money from the pockets of other organizations that want to build affordable housing. The bottom line is, we don't need to give away the store to get affordable housing."

Myopia over land use

Law professor Been offered some general comments about the conundrum faced in such projects. It’s difficult to define the community affected that should be at the table, to decide who speaks for that community, and how to fit negotiations over community benefits into broader land use processes.

"I'm going to put to one side the obvious questions that this raises, which is: 'Why isn't the government speaking for the community?' What's wrong with our processes?"

Lewis chuckled derisively.

Been continued, "One justification for the land use process, as it's set up, is so that you have a broader perspective, so you don't necessarily have the local community defining issues about housing that may affect the city as a whole."

She acknowledged that community input can bring value; she cited ACORN's focus on the need for senior housing at Atlantic Yards that, as Lewis pointed out, would accommodate not just singles but seniors raising grandchildren.

"On the other hand," she said, "we also have to be concerned: Are we thinking about it from a wide enough lens? And how can we shape our land use processes so we're getting more of that?"

Pushing the contradictions

|

| Lander & Lewis/Pratt Center. |

Lander said that it was painful for him, as an advocate of mixing affordable housing and good jobs with livable neighborhoods, that Atlantic Yards and other market-led development challenges both sets of interests. It leads “equity advocates” to accept more market-rate housing if it brings benefits, while “livability advocates” want less development because it inflicts less environmental harm.

"It sets up a painful and challenging conflict," he mused. “Maybe other land use procedures--ones that put planning earlier and up front wouldn’t lead to this dynamic, but we wind up in it an awful lot of the time."

"My sense is that Bertha and Candace really care about both issues," he continued , and posed the first question to Lewis. "You've long worked for livable neighborhoods," he said, citing past ACORN efforts fighting government overreach. “Are you concerned, in sort of reaching for these benefits [for the Atlantic Yards plan], that neighborhood residents on the livability issue are going to suffer?”

Lewis offered a rhetorical shrug. “We’ve been suffering, before anybody even thought about livability," she said. "My members have not had livability.” She returned to the point that the Atlantic Yards plan would provide far more affordable housing than other new developments.

Lewis offered a rhetorical shrug. “We’ve been suffering, before anybody even thought about livability," she said. "My members have not had livability.” She returned to the point that the Atlantic Yards plan would provide far more affordable housing than other new developments.

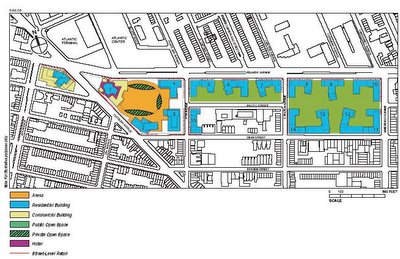

Lander tried to turn the conversation back to scale. (Sketches by Frank Gehry are adapted from the 7/5/05 New York Times; the project is expected to change.)

"My members suffer from asthma," Lewis said. "For us, traffic, density, how this stuff is done, we've been the victims of it. ACORN had to make a decision. And it's hard. What do you know about? What do you deal with? We know about housing. We’re concerned about traffic, hell yeah. We’re concerned about density, hell yeah. But here’s what we know. Not trying to overreach, not trying to deal with stuff that we don't have the resources or the expertise in, and we hope that those who have the resources and the expertise will sit down with us and work with us about solving this." (Wasn't that what Lander was trying to do?)

"We had to make a decision," Lewis continued. "We're human beings. This affects us. But we decided if we could make one nudge, one impact, what we could do, what we could kick ass on, it would be housing. I can't kick ass on environment, just can't. Can't do it on density, just can't. It’s reality. Of all the things that are happening in central, downtown Brooklyn, throughout Brooklyn--this is like a goddamn tsunami. It’s for real, this shit is coming. So, if I could stop one iota of gentrification, I’ll do it. I can't do environment. I can’t do traffic. But we're not just singleminded and coldhearted. My members experience this. But as an organization we need to be able to impact what we need to impact.”

Lander asked Carponter if protecting the sense of community would make it less inclusive. “We’re not against affordable housing,” she said. “We support doing it responsibly.”

She cited the community-developed UNITY Plan which proposed buildings of no more than 12 stories built on the railyards themselves. “The difference is, we did it with the community. We didn't let the developer decide what was good for us."

Lewis tried to interject, Lander tried to stop her. Lewis spoke over Lander: “No, no, no. That's not correct. That's not right. She can’t get away with it. For 30 years, the yards sat.” (Well, so did much of the already cleared and prepared urban renewal area north of the railyards, such as the sites for the Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal malls, until the 1990s property boom.)

Lander observed that, if Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn succeeds in stopping FCR, there’s a reasonable possibility nothing will happen, with a lot less affordable housing in a gentrifying neighborhood.

“That’s for real,” Lewis chimed in.

Carponter said no, that the rival Extell plan, which is limited to the railyards, could be implemented. “I don’t believe there will be no development. If there is not development, that would be the MTA's fault, because they didn't do it in the proper way.” (Left unspecified was that a 50/50 plan in a smaller project would provide less total housing and thus less affordable housing.)

The dispute intensifies

Lewis tried to interject. Lander, with the microphone, wanted to let the audience speak. The first questioner yielded the floor to Lewis.

“Number one,” she said. “I want to see the first lawsuit on the Downtown Brooklyn plan.... Eminent domain is all right when you’re displacing black and brown folks in poor neighborhoods.” (The Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, unlike the Atlantic Yards plan, went through the city’s land use process and was approved by City Council.)

“Number one,” she said. “I want to see the first lawsuit on the Downtown Brooklyn plan.... Eminent domain is all right when you’re displacing black and brown folks in poor neighborhoods.” (The Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, unlike the Atlantic Yards plan, went through the city’s land use process and was approved by City Council.)

“The neighborhood is not low-rise,” she added. "The neighborhood is high-rise." Actually, it's more mixed. Below the railyards, the immediate neighborhood is mostly low-rise; one of the tallest nearby buildings is the nine-story Newswalk building that has been sliced out of the project.

If you cross broad Atlantic Avenue (pictured), there are five buildings of subsidized housing that are up to 15 stories and one public housing building that is 31 stories; in between them are row houses. Also across Atlantic, near the western border of the project, is the Williamsburg Savings Bank, which has several setbacks but reaches 512 feet. Nearby is the Bank of New York tower over the Atlantic Terminal mall, over 300 feet. There would be 16 towers in the FCR plan with several over 300 feet and one 620 feet.

As for tall towers, Lewis said, “I don’t like 'em, but we're still in flux here."

“I cannot you who have never built affordable housing to sit there and say that we’re taking away three times as much affordable housing dollars... you’re just telling a lie.” (I asked the Fifth Avenue Committee's de la Uz afterward about that; she said that the costs were unclear, given that FCR had not yet released financial statements.)

And Lewis turned back to the larger issue. “The government has excluded the community.... When you want to talk about community, please, Candace, put in class, because that was the one thing that you left out." (Carponter noted afterward that she did point out the plan concerned ethnic, racial, and economic diversity.)

"The deal is this: Do we look at what is happening at the 48 other developments.... If you have the resources to take that class action suit to the other 48, if you do it, Candace, I'm down with you. If you only single out this one, which may be symptomatic or not, I’m not down.” (Well, this project is the largest in the history of Brooklyn and is proceeding without any city input. And there's no class-action suit.)

Turning on the moderator

Lander even got hit with a confrontational question, as Stephen Witt of the Courier-Life chain asked him if he had a chance to be part of the Community Benefits Agreement and, if so, why not. He also accused the Pratt Center of doing “a survey [of Prospect Heights] that was 98 or 90some percent white... How partisan are you?”

Witt was apparently referring to an October 2004 poll conducted for the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council, which was criticized by BUILD for only sampling two percent of the residents, with 61 percent of the respondents white.

Lander responded, “It was substantially more diverse than what you reference,” noting that the survey was aimed at residents in the immediate vicinity of the project footprint. He added that he was not asked to participate in the CBA discussions: “We’re policy wonks.”

Lander, former executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, called on its current director, de la Uz, for a question, and she prefaced it with a stakes-defining declaration of her own.

A ten-story, 80-unit project FAC is constructing, on a plot of urban renewal land (below) just across from the Atlantic Yards footprint--next to the Atlantic Center mall and three-story row houses, and near a 15-story subsidized building--would actually provide better affordability than the Atlantic Yards project: only 25 percent market-rate, 25% affordable to moderate- and middle-income people, and 50 percent affordable to those earning 80% of Area Median Income (about $50,000) and below. (Then again, the attempt at a reasonable scale produces 60 units of affordable housing; 16 such buildings would produce 960 units.)

“We’ve also organized rent-stabilized tenants in the project footprint," de la Uz continued. "I think Brad posed an important question about livability versus equity. I appreciate that Bertha said that ACORN made choices. I know those are things that the Fifth Avenue Committee is faced with every day, about where we're going to focus our efforts.... I wonder if, at the end of the day, we don't undermine who we are and what our vision is, and what our values are, if we choose one over the other.”

“We’ve also organized rent-stabilized tenants in the project footprint," de la Uz continued. "I think Brad posed an important question about livability versus equity. I appreciate that Bertha said that ACORN made choices. I know those are things that the Fifth Avenue Committee is faced with every day, about where we're going to focus our efforts.... I wonder if, at the end of the day, we don't undermine who we are and what our vision is, and what our values are, if we choose one over the other.” Lewis responded that the issue was "about black and brown people in Central Brooklyn."

"I appreciate that," de la Uz continued. "Our mission is very much the same. I think it's an issue of helping familes so folks have schools, and that folks can cross the street when they're getting to and from work. And that they have a chance to live with dignity." Her question to Lewis, was when a "real pro forma” has been released regarding the developer’s projected costs per dwelling unit.

Lewis shot back, “How many pro formas have you seen for all 49 projects in Brooklyn? How many? Give me a number."

de la Uz replied, "Probably eight of the nine" that include affordable housing.

Closing clash

Lewis returned to her mantra. “If we can stop gentrification one iota, we will do it. If we can make sure that low-income, moderate-income black and brown people can actually have a piece of this whole renaissance of downtown Brooklyn, we will do it,” she said. “What saddens me is the polarization of folks in downtown Brooklyn versus the rest of the Brooklyn. We really need some assistance to hold developers accountable.”

Carponter, a real estate lawyer rather than an affordable housing expert, had been playing defense against Lewis, but in her close, she unsheathed some rhetorical weapons. “If this is such a terrific process,” she asked, "the MOU shouldn't legally bind her to speak only in support of the project, and that's what it does."

Lewis sprang up contentiously.

"I'll show you the language," Carponter said, with a touch of weariness, and began reading the text, which requires ACORN to “to take reasonable steps to publicly support the Project.” Carponter added, "She is required by her agreement, to publicly support the project, she can't speak out against it."

Lewis interjected, “If the project sucks, I’ll speak out.”

Carponter continued, “If the project is so great, the agreement they have with tenants who are being displaced--the temporary relocation agreement--would not contain a gag order" that requires them to publicly support the project.

And, she added, "If the project is so terrific, if it's using government money in the amounts that it is, using the extreme power of eminent domain, then minimally we are entitled to a public process with government oversight and legislative review."

Lewis responded by changing the subject, blaming Carponter herself for eminent domain in the Downtown Brooklyn plan approved by City Council: "Talk about those 130 folks you displaced, Candace."

Broken system

Been, the academic, got the last word, lamenting the lack of planning. “We're dealing with 49 developments. We're dealing with one rezoning at a time. We don't have a comprehensive look at what's going on where and where we're going to put the affordable housing, where we're going to put the density and allow that affordable housing."

"The other issue is, it's too little, too late. Late in the game, after an environmental impact statement, is not when you want to be having everybody air what their problems, either the livability issues, the affordability concerns. One question that ought to be on the table is, at what cost is all this? Many people want affordable housing, but obviously affordable housing costs something. And the question is--"

"They don't want to pay for it," Lewis interjected.

Been continued, "In terms of public subsidies, is this the best thing for our public dollars? But we have too little information, and too little participation. One of the take home messages is we need to use this opportunity to figure out how to fix the system more broadly so we're not having these kinds of fights later in the year or decades."

Afterward, Lewis, a middle-aged black woman questioned by four younger, white reporters, held her ground combatively. “We don’t know what the state is going to allow Bruce Ratner to do,” she said. “Whatever the state allows him to do, the deal is 50/50.”

The questions, measured but insistent, continued. “You guys are so fucking disrespectful,” she declared. "You would not ask Extell this. Don't talk to me, talk to the state." One of her associates approached and urged Lewis to leave with them, and the conversation ended.

Comments

Post a Comment