Updated with documents embedded at bottom, as well.

How did the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) respond to nine letters in response to the Atlantic Yards Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) received in the final weeks and days before project approval?

The agency downplayed or ignored some crucial comments, as the agency responded to one ten-page letter in just two paragraphs and refused to fully address a crucial question about housing subsidies, according to newly-released documents, obtained via a Freedom of Information Law request.

Moreover, the ESDC delivered 600 pages of data requested by two transportation consultants just two days before the project was approved, and large questions remain about the impact on traffic and transit.

However, when the ESDC approved the Atlantic Yards project on 12/8/06, the four board members present were told by the agency’s Rachel Shatz, “Staff with our consultants carefully considered all the comments and determined that no new issues had been raised, and there is no need for any additional analysis in light of the information and conclusions in the FEIS.” (That mirrored the status memo accompanying the letters.)

That day I asked for copies of the letters and the agency's responses. Then-ESDC Chairman Charles Gargano said “of course.” Instead, the agency directed me to file a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request. I did so, and on 1/4/07—well after the project was approved by the state Public Authorities Control Board on 12/20/06—I was sent copies of the documents.

(The agency's 28-page response (4.8MB) was prepared by the consultants AKRF. It contains summaries of all the comments, which are delineated in individual documents linked below.)

New issues?

Were new issues raised? Of the nine letters, all but one (a generic letter of support) raised significant criticisms about issues like traffic, security, and open space. In most cases, the ESDC simply referred back to its answers in the Response to Comments chapter of the FEIS, asserting that the criticisms had met with response.

So the ultimate answer may come in court, when an expected challenge to the environmental review questions whether the agency conducted the required “hard look.”

Among the nine letters, one was received the day before the meeting and two were received on the day of the meeting. Despite the time pressure, the ESDC’s consultants--AKRF and Philip Habib and Associates--offered reasonably lengthy responses to nearly all the comments, mainly by citing previous answers.

Dismissing P.C. Richard

Curiously, however, the ESDC offered cursory responses—just two paragraphs—to a detailed letter (2.9MB) on behalf of A. J. Richard & Sons, owner of the P.C. Richard electronics store at Flatbush and Fourth avenues, a company that has not publicly protested the project. (The property is in white at the far west of the map, which is not completely current.)

Curiously, however, the ESDC offered cursory responses—just two paragraphs—to a detailed letter (2.9MB) on behalf of A. J. Richard & Sons, owner of the P.C. Richard electronics store at Flatbush and Fourth avenues, a company that has not publicly protested the project. (The property is in white at the far west of the map, which is not completely current.)

The company submitted a ten-page analysis from the Freudenthal & Elkowitz Consulting Group of Islandia, NY. Five pages concern whether the AY project, which has variants with more residential space and more office space, deserved instead a Generic Environmental Impact Statement.

The ESDC’s response: because the variation only involves three of 17 buildings, it’s not a threshold issue.

Over another five pages, the consultants questioned conclusions in the FEIS. For example, the consultants took issue with the state's assertion that, in general, any crowd noise surrounding the arena would be expected to be masked by noise from vehicles on adjacent streets and would not be a major noise source. They noted that no evidence was provided in support of that statement.

They pointed out that, while the FEIS cites a wind study, “supporting documentation is neither provided nor referenced.” (I was provided a copy separately from the FEIS.)

They also took issue with ESDC responses that the state need not address the sources of funding for the anticipated health care and day care centers within the project, which the state refers to as “amenities.”

Though several other issues were raised, the ESDC summarized the five pages of comments into the following:

The FEIS makes conclusory and self-serving statements, provides non-responsive or inconsistent answers. Such responses do not satisfy the “hard look” requirements of SEQRA.

The agency's response was dismissive:

The comment is inaccurate; the FEIS presents a thorough analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the proposed project. The conclusions presented in the FEIS are based on the CEQR Technical Manual and other relevant guidance, detailed analysis, and application of expert professional judgment. All substantive comments have been appropriately addressed and the lead agency has conducted the “hard look” required under SEQRA.

(CEQR is City Environmental Quality Review and SEQRA is the State Environmental Quality Review Act.)

Housing subsidies under wraps

The Municipal Art Society (MAS), in its letter, pointed out that the FEIS had not addressed a key question about housing subsidies:

In order to accurately assess whether the Atlantic Yards proposal will result in a net gain of affordable housing units, there needs to be an accounting of the public expenditures on this project versus the total amount of public subsidies available in the same fiscal year so that decision makers can accurately assess the public costs versus the public benefits. What percentage of the city’s total funds for housing will be required to build the project’s 2250 units?

The ESDC’s response cited, among other things, Response G-48 in the FEIS, which doesn’t directly answer the question:

The project sponsors would utilize affordable housing incentives that are available to any other developer in New York City. As discussed in Chapter 20, “Alternatives,” the proposed project site is particularly well-suited for mixed-income housing, and the provision of affordable units at this location has major benefits for low- and moderate-income residents.

Signage questions

The MAS, which has raised significant questions about project signage, said it’s difficult to interpret the ESDC document, which cites “opaque” and “transparent” signage as well as “advertising” and “accessory” signs:

One can only conclude that the FEIS is not being forthcoming with what the signage will actually look like, and one can easily make the assumption that the Urban Room will be covered by opaque changeable (video) signage soaring to 150 feet high. This type of signage will clearly be visible to the surrounding brownstone community and will create an adverse impact for local residents.

The ESDC responded without addressing the claim about 150-foot high signage:

The description of the signage and the conclusion made by the commentor are incorrect. The description of the signage set forth in the FEIS is accurate and consistent with the Design Guidelines. Opaque signage would not be allowed on the arena “volume façade.” Opaque signage is limited to a height of 40 feet on Building 1. Opaque signage on the urban room is limited to the westernmost 75 feet of the building and to no more than 50 percent of that area.

Security redux

In their letters, both the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods (CBN) and Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) attorney Jeff Baker raised the issue of security. The ESDC repeated a previous response:

Emergency scenarios such as a large-scale terrorist attack similar to the World Trade Center attack, a biological or chemical attack, or a bomb are not considered a reasonable worst-case scenario and are therefore outside of the scope of the EIS. However, as indicated in Chapter 1, “Project Description,” the proposed project would implement its own site security plan, which includes measures such as the deployment of security staff and monitoring and screening procedures…. Consultation with NYPD and FDNY has been taking place and would continue should the project move forward. Disclosing detailed security plans is not appropriate for an EIS.

(CBN also raised broader concerns.)

Emergency response delays?

DDDB attorney Baker, in his letter, criticized the state’s assertion that emergency responders wouldn’t be hampered: Faced with gridlock conditions, the FEIS states that emergency vehicles will not be hampered because police, fire and ambulance vehicles “are not bound by standard traffic controls” when responding to emergencies.” Apparently when faced with gridlock, the traffic magically parts to make way for the vehicles without delay—a miracle of modern physics that has not been witnessed in other gridlock events.

The ESDC said Baker’s wrong, citing this previous response:

The increases in traffic associated with the proposed project would not significantly affect NYPD response times generally because the four precinct headquarters are located throughout the project’s study area and are not clustered around the project site. NYPD vehicles, when responding to emergencies, are not bound by standard traffic controls and are capable of adjusting to any congestion encountered en route to their destination and are therefore less affected by traffic congestion. These vehicles would be able to access the project site as they do other areas throughout New York City, including the most congested areas of Midtown and Downtown Manhattan.

(Emphasis added)

The agency added:

[P]olice and fire stations are widely distributed around the project site, so emergency vehicles would have numerous routes available for responding to emergencies. The FEIS properly indicates that NYPD and FDNY vehicles are capable of adjusting to congestion, as they do in many areas of the city.

Crime and blight

DDDB’s Baker criticized the ESDC’s Blight Study, noting for example, while the study characterizes the project site as crime-ridden, the statistics are misrepresented and the FEIS ignored this critical point.

The ESDC responded by saying the complaint was off-topic:

The Blight Study was attached to the GPP [General Project Plan] and was not part of the EIS. The DEIS and FEIS accurately describe the blighted conditions at the project site.

Indeed, the GPP, rather than the FEIS, contained the blight study, but the ESDC seems to be having it both ways. In Chapter 24 of the Final EIS, the ESDC spent six pages responding to questions about blight and eminent domain, and defended other aspects of the blight study.

Violations of the UDC Act?

DDDB’s Baker made several charges regarding the Urban Development Corporation (UDC) Act, the law that established the ESDC:

DDDB and others noted that ESDC has violated Sec. 16 of the UDC Act by failing to hold the comment period open until October 18th, 30 days after the last public hearing on September 18th. The FEIS… continues the absurd contention that the public hearing was on August 23rd and the September 18th event was a “community forum”...

DDDB also noted that the project does not meet the legal definitions of a civic project or a land use improvement project. Those comments are not recognized or responded to in the FEIS. These are fundamental questions that go to the public need, purpose and authority of ESDC to undertake the action and override local land use controls. The lack of response is a striking admission that ESDC is operating beyond its authority.

The ESDC responded without any detail:

The lead agency followed all procedures required under the UDC Act.

Bad math on open space

Baker observed that the ESDC had miscalculated open space ratios, as I and other had pointed out:

The FEIS responds that the project provides 1.7 acres per 1,000 residents. (FEIS p. 24-169) However the math is wrong. Per the FEIS, there will be approximately 13,503 residents based on the assumption of 2.1 persons per unit. That results in a ratio of 0.59 acres per 1000 residents far less than the 1.7 acres represented in the FEIS. This fundamental mathematical error is indicative of the carelessness of the FEIS and should put the Board on notice that there has not been sufficient analysis to warrant approval of the project.

The ESDC responded by saying the error wasn’t important:

The computation is not relevant to the open space analysis in Chapter 6 of the FEIS… The proposed project would provide approximately 0.6 acres per 1000 residents, not 1.7 acres per 1000 residents. This error does not affect the FEIS analysis in any way and does not change the conclusions iterated in Response 6-6 that 1) although the open space ratio for the proposed project is less than the citywide goal of 2.5 acres per 1000 residents, the citywide goal is not feasible and not achievable for many areas of the city and is not considered as an impact threshold for CEQR purposes, and b) the proposed project would not result in significant adverse open space impacts upon completion in 2016.

In other words, even though the open space ratio would be about a third of what was claimed, and one-quarter of the citywide goal, the goal is just a target and there’s no minimum threshold.

Backdating a change?

The ESDC may have backdated a change in the FEIS in order to placate a commentor. Brent Porter, who teaches at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture, wrote that the agency had reported, in the FEIS, that he had only provided verbal testimony:

However, I submitted written testimony which included solar shadowing diagrams which were contrary to those published in the DEIS [Draft EIS].

The ESDC response:

The ESDC response:

The written submission is acknowledged in Chapter 24 of the FEIS issued on November 27, 2006.

Not quite. While Porter’s oral and written submissions are, in fact, acknowledged in Chapter 24 of the FEIS dated November 27, 2006 and available at the ESDC web site (above), that may have been an addition made sometime after that date. A compact disc dated November 27, distributed to reporters after an ESDC meeting that day, refers (right) only to Porter’s oral comments. That disc did include Porter’s written comments, but it did not cite them in the list of those submitting comments.

A compact disc dated November 27, distributed to reporters after an ESDC meeting that day, refers (right) only to Porter’s oral comments. That disc did include Porter’s written comments, but it did not cite them in the list of those submitting comments.

Shadow effects

Porter argued that the EIS ignores buildings that would be shadowed but face away from the site. The ESDC cited Response 9-3 in the FEIS, which states, in part:

Streets, sidewalks and private backyards are not considered sun-sensitive resources or important natural features according to the CEQR Technical Manual.

Porter also commented that the EIS ignores the value of sunlight being blocked, given potential photovoltaic roofs and walls, and passive solar heating. The ESDC cited Response 9-11, which states:

Shadows move across the landscape throughout the day, and are not perpetual. No substantial additional energy usage would occur due to incremental shadows.

[emphasis added]

It also cites its response to the Fifth Avenue Committee’s statement that its planned Atlantic Terrace building, on the north side of Atlantic Avenue just east ofthe Atlantic Center mall, has had to eliminate use of photovoltaics because of shadows from the Atlantic Yards project. The ESDC reply:

Details were not provided to substantiate the elimination of photovoltaics due to the proposed project…All in all, during the late spring and summer months, the optimal time for harvesting solar energy, the incremental shadows are of short duration and do not cover the entire space.

Traffic and transit

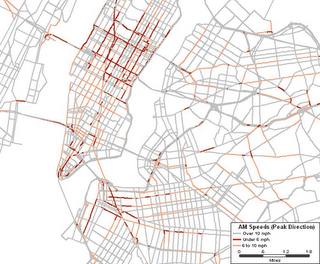

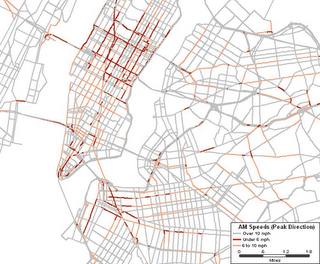

The most detailed and contentious exchanges involved analyses of traffic and transit, especially criticisms (1.9MB) from Brian Ketcham and Carolyn Konheim of Community Consulting Services (CCS). They received 600 pages of background data less than two days before the ESDC voted to approve the project.

“Their responses to our comments is we agree to disagree,” Ketcham told me. “We think we’ve demonstrated it won’t result in the impact they’re claiming. The city and state should be working on behalf of the public, instead they’re working on behalf of the developers to get projects approved.”

He warned that the congestion would be more severe than acknowledged, and that it was irresponsible to claim that no more subway capacity is needed. “Those two issues are going to impact the community the greatest,” Ketcham said.

(Note that Joe Chan of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership said at a community meeting in November, “Our mass transit system is pretty much at capacity when we look at linkages between Downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan.” And Kenn Lowy of Community Board 2's Transportation Committee has pointed out that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 2004 said that the Downtown Brooklyn stations were at capacity. The project, most of which would be just east of Downtown Brooklyn and much of which would use the Atlantic Avenue transportation hub, would add to that usage.)

Mitigation for concerts?

CCS pointed out that the ESDC doesn’t offer mitigation for traffic coming to events other than Nets games, which are not analyzed on the unsubstantiated premise that they would likely attract fewer auto trips.

ESDC cited its FEIS response, which suggests that a Nets basketball game would typically attract substantially more spectators than would a typical concert or other large event at the arena. In addition, data from Madison Square Garden indicates that concert attendees have a 16 percent lower auto/taxi mode share than basketball fans, and a correspondingly higher transit share.

Also, the agency acknowledged, the diversity of event promoters means that there’s be no way to for the project sponsors to market the traffic management measures like remote parking with shuttle buses.

Wrong peak period?

CCS argued that, because games start at 7:30 pm, the pre-game peak period studied should have been 6:30-7:30 pm, not 7-8 pm:

The preparers of the FEIS wiggle through an argument that Madison Square Garden data suggests as much as 30% of game-goers arrive in the half-hour after the game begins.

Indeed, the FEIS quotes data that says that 29% of MSG attendees arrive in that half hour, 42% in the half-hour prior to the game, and only 19% between 6:30 and 7 pm. CCS pointed out that the agency has not made “such anomalous data open to inspection.” (Do nearly one-third of those going to basketball games miss the first quarter?)

Data release timely?

CCS pointed out that the ESDC refused to release traffic data on the gratuitious assertion that the worksheets were reviewed by NYCDOT and the false claim they are not normally included in an EIS. In fact, the same consultant team has provided worksheets along with detailed trip generation and trip assignment diagrams for all No Build projects for the Downtown Brooklyn Plan DEIS.

The ESDC response: traffic-related information requested on November 30 has been provided.

As noted, that data was received just two days before the ESDC vote. “That takes months to pore over,” Ketcham told me. “It’s too late to be of any consequence.”

Overloaded access routes?

CCS said the FEIS ignores the cumulative impact of added project trips to overloaded access routes, such as the BQE and the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, where seemingly small increments can result in queues reaching into Manhattan. CCS’s model shows areawide gridlock.

In its response, the ESDC referenced the FEIS (12-19):

Given the numerous corridors providing access to the project site, including Atlantic, Flatbush, Carlton, Vanderbilt, Washington, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th Avenues, project-generated traffic is expected to be dispersed to the north, south, east, and west, and is expected to become rapidly less concentrated with increasing distance from the project site. For these reasons it is expected that there would not be significant impacts on the regional access corridors.

The ESDC also cited pages 80-81 of Chapter 12 of the FEIS, which acknowledges congestion but suggests it’s not significant:

As the changes in traffic flow density on the two bridges would therefore remain below the CEQR Technical Manual threshold… in each analyzed peak hour, no significant adverse impacts to traffic flow on the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges as independent facilities are anticipated to result from the proposed project. It should be noted, however, that some future queuing would likely occur on the bridges (as is presently the case) due to congestion at the metering intersections during peak periods.

The question is: what does "some future queuing" mean?

Traffic calming

CCS said the FEIS ignores the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Downtown Brooklyn Traffic Calming Project (DBTCP). The ESDC responded (12-14):

As discussed in the DEIS, with the exception of the conversion of Smith Street from two-way to one-way northbound operation, recommendations from the DBTCP were not incorporated into the traffic analyses as no other specific measures have been identified by NYCDOT for implementation at this time.

That seems contradicted by the DOT’s statement:

A number of improvements to Downtown Brooklyn’s transportation infrastructure have been implemented in recent months or will be implemented shortly.

Congestion pricing

CCS and others pointed out that the ESDC didn’t address congestion pricing, which could be the most significant mitigation measure, as a citywide program could change daily traffic patterns.

CCS and others pointed out that the ESDC didn’t address congestion pricing, which could be the most significant mitigation measure, as a citywide program could change daily traffic patterns.

(Congestion graphic from Battling Traffic: What New Yorkers Think about Road Pricing.)

The ESDC responded by citing a very limited concept of congestion pricing, regarding Nets games rather than an areawide policy:

In addition, congestion pricing has also been incorporated in the proposed mitigation plan in the form of a surcharge that would be imposed for on-site arena parking on game days.

NYC concurrence

CCS criticized the ESDC for not accounting sufficiently for growth in Brooklyn and its effect on the transit system:

[T]he FEIS claims the projected subway ridership by line was approved by NYC Transit, but provides no correspondence from NYC Transit indicated its concurrence, as with the City agencies, a typical requirements of FEISs.

The ESDC response does not attach correspondence:

As indicated in the FEIS, NYCT has reviewed and concurred with the transit analysis.

Konheim commented, “I think they regurgitate the responses in the FEIS response to comments, they count on nobody really looking to see if they actually answered those questions in the comments, and they brush aside the substance of comments where they don’t have a specific response by saying, ‘Oh, they were approved by the agencies.’”

Accessory parking

CCS commented that the zoning and financing for the Long Island College Hospital (LICH) garage prohibited it from being used as accessory parking on game nights.

The ESDC responded that it would all work out:

All necessary approvals for utilization of the LICH garage for remote parking would be obtained.

(Emphasis added)

Demapping streets

Urban planner Vaidila Kungys submitted numerous comments, some of which were ignored in the FEIS. After that document was issued, he further commented (3.6MB; note that the ESDC copy does not preserve his color coding) to the ESDC.

For one thing, he said that the FEIS had failed to address his comment on the demapping of streets, which he said would adversely affect traffic congestion, safety, and pollution. The ESDC responded that it had addressed the comment in the FEIS, citing Response 12-10, which explains why parts of Fifth Avenue and Pacific Street would be closed:

As discussed in the DEIS, the closures of these street segments would reduce the number of pedestrian crossing locations and the number of vehicle turning movements in the vicinity of the project site, thereby reducing the potential for vehicle/pedestrian conflicts at some locations. At other locations, however, it is acknowledged in the DEIS that the proposed project would result in an increase in vehicle and pedestrian trips and therefore an increased potential for conflicts. The traffic analyses in the DEIS account for the traffic that would be diverted as a result of these closures, and the proposed project and its traffic mitigation plan include a range of design elements and physical and operational measures to improve traffic and pedestrian flow and enhance safety.

Kungys went over that response and told me:

I believe that AKRF’s response does not accurately address my concern, which is overall safety... The claim is that by demapping streets, some locations have the potential to be made safer since cars won’t be there, but it does not explain how overall safety will be met. Why? Because, simply put, demapped streets relate to more cars driving on fewer roads thereby adding to traffic congestion, making the overall conditions less safe for pedestrians, bicyclists, and other motor vehicles.

Urban design criticism

Kungys told the ESDC:

It is likely that a drastically different environment will isolate and separate the existing neighborhood from the new neighborhood, especially considering the breaks in the street wall, and enormous heights (that will cause increased shadows), and demapped streets, which hold together the sense of connections in urban settings.

The ESDC cited its response (8-2) in the FEIS:

As stated in the DEIS in Chapter 8, “Urban Design and Visual Resources,” the proposed project’s residential blocks would establish physical and visual connections to the neighborhoods located north, south, and east of the project site. The Design Guidelines require that each of the residential buildings has a strong streetwall component... The Fort Greene street grid north of the project site would be extended physically and visually as pedestrian paths into and across the eight-acre open space component of project site... . The access points would be a minimum of 60 feet wide, comparable to the width of a neighborhood street (the east–west connections would be wider), and would be landscaped with easily identifiable streetscape elements.

Upon seeing that, Kungys commented:

Response 8-2 discusses street walls, pedestrian access points, and visual connections but does not respond to the issue that the de-mapped streets would alter the street pattern and urban design significantly. Removing over a ¼ mile of public roads destroys the urban fabric. Therefore, demapped streets would adversely affect urban design and view corridors simply because they would no longer be public streets—regardless of the benches, trees, etc. that are brought there, the demapped streets would sever the public right of ways and thereby negatively alter the urban design, visual corridors, and street patterns and street hierarchy.

Open space

Kungys criticicized the DEIS for not taking an alternative plan, which would include an arena and significantly smaller buildings, more seriously:

In 6-28 the EIS, discussing the Reduced Density Arena Alternative, states that “The pocket parks would be surrounded on three sides by new residential buildings; therefore, they may not be perceived as public parks by other residents of the community.” Nevertheless, this is not mentioned in the Chapter 6 (Open Space) for the proposed project. Why not? The DEIS fails to be consistent in methodology. If it is assumed that pocket parks surrounded on three sides may not be perceived as public parks by other residents for the Reduced Density Arena Alternative then, by the same logic, it should require the EIS to state that residents would similarly not perceive open space within the Proposed Plan as public space.

The ESDC responded:

The connective qualities of the proposed project’s open space and the deficiencies of the open space under the Reduced Density alternatives are described in Chapters 6, “Open Space and Recreational Facilities” and 20, “Alternatives,” respectively.

Kungys commented:

My comment was about the consistency of the EIS, not connective qualities relating to the project. The response failed to address my concern because the proposed project would create places just like the Reduced Density Arena Alternative’s pocket parks; it would create spaces that would not be perceived as public because they would be recessed within a private development. The EIS’s inconsistent reasoning is based on bias, not reason.

Alternatives

Kungys suggested that the Reduced Density Arena Alternative has a better park plan, criticizing the state’s statement that a park bordering heavily trafficked Atlantic Avenue would be a bad idea. He wrote:

Nevertheless, streets border many of our best parks: Bryant Park, Central Park, Fort Greene Park, Prospect Park, Union Square, Tompkins Square, Washington Square, just to name a few. The Reduced Density Arena Alternative’s park would be qualitatively better than most of the proposed project’s open space because it would clearly be public due to the fact that it would be surrounded by streets and not nestled within a private mixed-use development.

The ESDC cited Response 20-12:

The Reduced Density—Arena Alternative provides for far less public open space (1.84 acres) than the proposed project (8 acres), and it would quantitatively reduce the availability of active and passive open space as compared to the no build condition. Thus, the amount of open space proposed under the Reduced Density—Arena Alternative would be inadequate to serve the residents and workers of the study area. In addition, the open space provided under this alternative would not provide for the variety of recreational opportunities planned with the proposed project.... The portion of the open space located between Carlton and 6th Avenues would be physically adjacent to the Pacific Street and directly accessible from the sidewalk. In addition, portions of the project’s open space would directly front Atlantic, Carlton and Vanderbilt Avenues and Dean Street.

After seeing that, Kungys responded:

My comment referred to the quality of the design, not the size of the park. More isn’t always better. After all, what good is a large park if it isn’t used? Also, we need to remember that the transfer of public roads (de-mapped streets) to publicly accessible private space instantly gives the proposed project most of that 8 acres of open space.

[Actually, the streets would be a significant but not majority component.]

He continued:

Nevertheless, the Reduced Density version would maintain the existing roads and add others to bring about more publicly accessible space for walking, cycling, driving, and to provide more access to light and air. Which park would you prefer: Fort Greene Park or the grass in Stuyvesant Town?

How did the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) respond to nine letters in response to the Atlantic Yards Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) received in the final weeks and days before project approval?

The agency downplayed or ignored some crucial comments, as the agency responded to one ten-page letter in just two paragraphs and refused to fully address a crucial question about housing subsidies, according to newly-released documents, obtained via a Freedom of Information Law request.

Moreover, the ESDC delivered 600 pages of data requested by two transportation consultants just two days before the project was approved, and large questions remain about the impact on traffic and transit.

However, when the ESDC approved the Atlantic Yards project on 12/8/06, the four board members present were told by the agency’s Rachel Shatz, “Staff with our consultants carefully considered all the comments and determined that no new issues had been raised, and there is no need for any additional analysis in light of the information and conclusions in the FEIS.” (That mirrored the status memo accompanying the letters.)

That day I asked for copies of the letters and the agency's responses. Then-ESDC Chairman Charles Gargano said “of course.” Instead, the agency directed me to file a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request. I did so, and on 1/4/07—well after the project was approved by the state Public Authorities Control Board on 12/20/06—I was sent copies of the documents.

(The agency's 28-page response (4.8MB) was prepared by the consultants AKRF. It contains summaries of all the comments, which are delineated in individual documents linked below.)

New issues?

Were new issues raised? Of the nine letters, all but one (a generic letter of support) raised significant criticisms about issues like traffic, security, and open space. In most cases, the ESDC simply referred back to its answers in the Response to Comments chapter of the FEIS, asserting that the criticisms had met with response.

So the ultimate answer may come in court, when an expected challenge to the environmental review questions whether the agency conducted the required “hard look.”

Among the nine letters, one was received the day before the meeting and two were received on the day of the meeting. Despite the time pressure, the ESDC’s consultants--AKRF and Philip Habib and Associates--offered reasonably lengthy responses to nearly all the comments, mainly by citing previous answers.

Dismissing P.C. Richard

Curiously, however, the ESDC offered cursory responses—just two paragraphs—to a detailed letter (2.9MB) on behalf of A. J. Richard & Sons, owner of the P.C. Richard electronics store at Flatbush and Fourth avenues, a company that has not publicly protested the project. (The property is in white at the far west of the map, which is not completely current.)

Curiously, however, the ESDC offered cursory responses—just two paragraphs—to a detailed letter (2.9MB) on behalf of A. J. Richard & Sons, owner of the P.C. Richard electronics store at Flatbush and Fourth avenues, a company that has not publicly protested the project. (The property is in white at the far west of the map, which is not completely current.)The company submitted a ten-page analysis from the Freudenthal & Elkowitz Consulting Group of Islandia, NY. Five pages concern whether the AY project, which has variants with more residential space and more office space, deserved instead a Generic Environmental Impact Statement.

The ESDC’s response: because the variation only involves three of 17 buildings, it’s not a threshold issue.

Over another five pages, the consultants questioned conclusions in the FEIS. For example, the consultants took issue with the state's assertion that, in general, any crowd noise surrounding the arena would be expected to be masked by noise from vehicles on adjacent streets and would not be a major noise source. They noted that no evidence was provided in support of that statement.

They pointed out that, while the FEIS cites a wind study, “supporting documentation is neither provided nor referenced.” (I was provided a copy separately from the FEIS.)

They also took issue with ESDC responses that the state need not address the sources of funding for the anticipated health care and day care centers within the project, which the state refers to as “amenities.”

Though several other issues were raised, the ESDC summarized the five pages of comments into the following:

The FEIS makes conclusory and self-serving statements, provides non-responsive or inconsistent answers. Such responses do not satisfy the “hard look” requirements of SEQRA.

The agency's response was dismissive:

The comment is inaccurate; the FEIS presents a thorough analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the proposed project. The conclusions presented in the FEIS are based on the CEQR Technical Manual and other relevant guidance, detailed analysis, and application of expert professional judgment. All substantive comments have been appropriately addressed and the lead agency has conducted the “hard look” required under SEQRA.

(CEQR is City Environmental Quality Review and SEQRA is the State Environmental Quality Review Act.)

Housing subsidies under wraps

The Municipal Art Society (MAS), in its letter, pointed out that the FEIS had not addressed a key question about housing subsidies:

In order to accurately assess whether the Atlantic Yards proposal will result in a net gain of affordable housing units, there needs to be an accounting of the public expenditures on this project versus the total amount of public subsidies available in the same fiscal year so that decision makers can accurately assess the public costs versus the public benefits. What percentage of the city’s total funds for housing will be required to build the project’s 2250 units?

The ESDC’s response cited, among other things, Response G-48 in the FEIS, which doesn’t directly answer the question:

The project sponsors would utilize affordable housing incentives that are available to any other developer in New York City. As discussed in Chapter 20, “Alternatives,” the proposed project site is particularly well-suited for mixed-income housing, and the provision of affordable units at this location has major benefits for low- and moderate-income residents.

Signage questions

The MAS, which has raised significant questions about project signage, said it’s difficult to interpret the ESDC document, which cites “opaque” and “transparent” signage as well as “advertising” and “accessory” signs:

One can only conclude that the FEIS is not being forthcoming with what the signage will actually look like, and one can easily make the assumption that the Urban Room will be covered by opaque changeable (video) signage soaring to 150 feet high. This type of signage will clearly be visible to the surrounding brownstone community and will create an adverse impact for local residents.

The ESDC responded without addressing the claim about 150-foot high signage:

The description of the signage and the conclusion made by the commentor are incorrect. The description of the signage set forth in the FEIS is accurate and consistent with the Design Guidelines. Opaque signage would not be allowed on the arena “volume façade.” Opaque signage is limited to a height of 40 feet on Building 1. Opaque signage on the urban room is limited to the westernmost 75 feet of the building and to no more than 50 percent of that area.

Security redux

In their letters, both the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods (CBN) and Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) attorney Jeff Baker raised the issue of security. The ESDC repeated a previous response:

Emergency scenarios such as a large-scale terrorist attack similar to the World Trade Center attack, a biological or chemical attack, or a bomb are not considered a reasonable worst-case scenario and are therefore outside of the scope of the EIS. However, as indicated in Chapter 1, “Project Description,” the proposed project would implement its own site security plan, which includes measures such as the deployment of security staff and monitoring and screening procedures…. Consultation with NYPD and FDNY has been taking place and would continue should the project move forward. Disclosing detailed security plans is not appropriate for an EIS.

(CBN also raised broader concerns.)

Emergency response delays?

DDDB attorney Baker, in his letter, criticized the state’s assertion that emergency responders wouldn’t be hampered: Faced with gridlock conditions, the FEIS states that emergency vehicles will not be hampered because police, fire and ambulance vehicles “are not bound by standard traffic controls” when responding to emergencies.” Apparently when faced with gridlock, the traffic magically parts to make way for the vehicles without delay—a miracle of modern physics that has not been witnessed in other gridlock events.

The ESDC said Baker’s wrong, citing this previous response:

The increases in traffic associated with the proposed project would not significantly affect NYPD response times generally because the four precinct headquarters are located throughout the project’s study area and are not clustered around the project site. NYPD vehicles, when responding to emergencies, are not bound by standard traffic controls and are capable of adjusting to any congestion encountered en route to their destination and are therefore less affected by traffic congestion. These vehicles would be able to access the project site as they do other areas throughout New York City, including the most congested areas of Midtown and Downtown Manhattan.

(Emphasis added)

The agency added:

[P]olice and fire stations are widely distributed around the project site, so emergency vehicles would have numerous routes available for responding to emergencies. The FEIS properly indicates that NYPD and FDNY vehicles are capable of adjusting to congestion, as they do in many areas of the city.

Crime and blight

DDDB’s Baker criticized the ESDC’s Blight Study, noting for example, while the study characterizes the project site as crime-ridden, the statistics are misrepresented and the FEIS ignored this critical point.

The ESDC responded by saying the complaint was off-topic:

The Blight Study was attached to the GPP [General Project Plan] and was not part of the EIS. The DEIS and FEIS accurately describe the blighted conditions at the project site.

Indeed, the GPP, rather than the FEIS, contained the blight study, but the ESDC seems to be having it both ways. In Chapter 24 of the Final EIS, the ESDC spent six pages responding to questions about blight and eminent domain, and defended other aspects of the blight study.

Violations of the UDC Act?

DDDB’s Baker made several charges regarding the Urban Development Corporation (UDC) Act, the law that established the ESDC:

DDDB and others noted that ESDC has violated Sec. 16 of the UDC Act by failing to hold the comment period open until October 18th, 30 days after the last public hearing on September 18th. The FEIS… continues the absurd contention that the public hearing was on August 23rd and the September 18th event was a “community forum”...

DDDB also noted that the project does not meet the legal definitions of a civic project or a land use improvement project. Those comments are not recognized or responded to in the FEIS. These are fundamental questions that go to the public need, purpose and authority of ESDC to undertake the action and override local land use controls. The lack of response is a striking admission that ESDC is operating beyond its authority.

The ESDC responded without any detail:

The lead agency followed all procedures required under the UDC Act.

Bad math on open space

Baker observed that the ESDC had miscalculated open space ratios, as I and other had pointed out:

The FEIS responds that the project provides 1.7 acres per 1,000 residents. (FEIS p. 24-169) However the math is wrong. Per the FEIS, there will be approximately 13,503 residents based on the assumption of 2.1 persons per unit. That results in a ratio of 0.59 acres per 1000 residents far less than the 1.7 acres represented in the FEIS. This fundamental mathematical error is indicative of the carelessness of the FEIS and should put the Board on notice that there has not been sufficient analysis to warrant approval of the project.

The ESDC responded by saying the error wasn’t important:

The computation is not relevant to the open space analysis in Chapter 6 of the FEIS… The proposed project would provide approximately 0.6 acres per 1000 residents, not 1.7 acres per 1000 residents. This error does not affect the FEIS analysis in any way and does not change the conclusions iterated in Response 6-6 that 1) although the open space ratio for the proposed project is less than the citywide goal of 2.5 acres per 1000 residents, the citywide goal is not feasible and not achievable for many areas of the city and is not considered as an impact threshold for CEQR purposes, and b) the proposed project would not result in significant adverse open space impacts upon completion in 2016.

In other words, even though the open space ratio would be about a third of what was claimed, and one-quarter of the citywide goal, the goal is just a target and there’s no minimum threshold.

Backdating a change?

The ESDC may have backdated a change in the FEIS in order to placate a commentor. Brent Porter, who teaches at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture, wrote that the agency had reported, in the FEIS, that he had only provided verbal testimony:

However, I submitted written testimony which included solar shadowing diagrams which were contrary to those published in the DEIS [Draft EIS].

The ESDC response:

The ESDC response:The written submission is acknowledged in Chapter 24 of the FEIS issued on November 27, 2006.

Not quite. While Porter’s oral and written submissions are, in fact, acknowledged in Chapter 24 of the FEIS dated November 27, 2006 and available at the ESDC web site (above), that may have been an addition made sometime after that date.

A compact disc dated November 27, distributed to reporters after an ESDC meeting that day, refers (right) only to Porter’s oral comments. That disc did include Porter’s written comments, but it did not cite them in the list of those submitting comments.

A compact disc dated November 27, distributed to reporters after an ESDC meeting that day, refers (right) only to Porter’s oral comments. That disc did include Porter’s written comments, but it did not cite them in the list of those submitting comments.Shadow effects

Porter argued that the EIS ignores buildings that would be shadowed but face away from the site. The ESDC cited Response 9-3 in the FEIS, which states, in part:

Streets, sidewalks and private backyards are not considered sun-sensitive resources or important natural features according to the CEQR Technical Manual.

Porter also commented that the EIS ignores the value of sunlight being blocked, given potential photovoltaic roofs and walls, and passive solar heating. The ESDC cited Response 9-11, which states:

Shadows move across the landscape throughout the day, and are not perpetual. No substantial additional energy usage would occur due to incremental shadows.

[emphasis added]

It also cites its response to the Fifth Avenue Committee’s statement that its planned Atlantic Terrace building, on the north side of Atlantic Avenue just east ofthe Atlantic Center mall, has had to eliminate use of photovoltaics because of shadows from the Atlantic Yards project. The ESDC reply:

Details were not provided to substantiate the elimination of photovoltaics due to the proposed project…All in all, during the late spring and summer months, the optimal time for harvesting solar energy, the incremental shadows are of short duration and do not cover the entire space.

Traffic and transit

The most detailed and contentious exchanges involved analyses of traffic and transit, especially criticisms (1.9MB) from Brian Ketcham and Carolyn Konheim of Community Consulting Services (CCS). They received 600 pages of background data less than two days before the ESDC voted to approve the project.

“Their responses to our comments is we agree to disagree,” Ketcham told me. “We think we’ve demonstrated it won’t result in the impact they’re claiming. The city and state should be working on behalf of the public, instead they’re working on behalf of the developers to get projects approved.”

He warned that the congestion would be more severe than acknowledged, and that it was irresponsible to claim that no more subway capacity is needed. “Those two issues are going to impact the community the greatest,” Ketcham said.

(Note that Joe Chan of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership said at a community meeting in November, “Our mass transit system is pretty much at capacity when we look at linkages between Downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan.” And Kenn Lowy of Community Board 2's Transportation Committee has pointed out that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 2004 said that the Downtown Brooklyn stations were at capacity. The project, most of which would be just east of Downtown Brooklyn and much of which would use the Atlantic Avenue transportation hub, would add to that usage.)

Mitigation for concerts?

CCS pointed out that the ESDC doesn’t offer mitigation for traffic coming to events other than Nets games, which are not analyzed on the unsubstantiated premise that they would likely attract fewer auto trips.

ESDC cited its FEIS response, which suggests that a Nets basketball game would typically attract substantially more spectators than would a typical concert or other large event at the arena. In addition, data from Madison Square Garden indicates that concert attendees have a 16 percent lower auto/taxi mode share than basketball fans, and a correspondingly higher transit share.

Also, the agency acknowledged, the diversity of event promoters means that there’s be no way to for the project sponsors to market the traffic management measures like remote parking with shuttle buses.

Wrong peak period?

CCS argued that, because games start at 7:30 pm, the pre-game peak period studied should have been 6:30-7:30 pm, not 7-8 pm:

The preparers of the FEIS wiggle through an argument that Madison Square Garden data suggests as much as 30% of game-goers arrive in the half-hour after the game begins.

Indeed, the FEIS quotes data that says that 29% of MSG attendees arrive in that half hour, 42% in the half-hour prior to the game, and only 19% between 6:30 and 7 pm. CCS pointed out that the agency has not made “such anomalous data open to inspection.” (Do nearly one-third of those going to basketball games miss the first quarter?)

Data release timely?

CCS pointed out that the ESDC refused to release traffic data on the gratuitious assertion that the worksheets were reviewed by NYCDOT and the false claim they are not normally included in an EIS. In fact, the same consultant team has provided worksheets along with detailed trip generation and trip assignment diagrams for all No Build projects for the Downtown Brooklyn Plan DEIS.

The ESDC response: traffic-related information requested on November 30 has been provided.

As noted, that data was received just two days before the ESDC vote. “That takes months to pore over,” Ketcham told me. “It’s too late to be of any consequence.”

Overloaded access routes?

CCS said the FEIS ignores the cumulative impact of added project trips to overloaded access routes, such as the BQE and the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, where seemingly small increments can result in queues reaching into Manhattan. CCS’s model shows areawide gridlock.

In its response, the ESDC referenced the FEIS (12-19):

Given the numerous corridors providing access to the project site, including Atlantic, Flatbush, Carlton, Vanderbilt, Washington, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th Avenues, project-generated traffic is expected to be dispersed to the north, south, east, and west, and is expected to become rapidly less concentrated with increasing distance from the project site. For these reasons it is expected that there would not be significant impacts on the regional access corridors.

The ESDC also cited pages 80-81 of Chapter 12 of the FEIS, which acknowledges congestion but suggests it’s not significant:

As the changes in traffic flow density on the two bridges would therefore remain below the CEQR Technical Manual threshold… in each analyzed peak hour, no significant adverse impacts to traffic flow on the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges as independent facilities are anticipated to result from the proposed project. It should be noted, however, that some future queuing would likely occur on the bridges (as is presently the case) due to congestion at the metering intersections during peak periods.

The question is: what does "some future queuing" mean?

Traffic calming

CCS said the FEIS ignores the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Downtown Brooklyn Traffic Calming Project (DBTCP). The ESDC responded (12-14):

As discussed in the DEIS, with the exception of the conversion of Smith Street from two-way to one-way northbound operation, recommendations from the DBTCP were not incorporated into the traffic analyses as no other specific measures have been identified by NYCDOT for implementation at this time.

That seems contradicted by the DOT’s statement:

A number of improvements to Downtown Brooklyn’s transportation infrastructure have been implemented in recent months or will be implemented shortly.

Congestion pricing

CCS and others pointed out that the ESDC didn’t address congestion pricing, which could be the most significant mitigation measure, as a citywide program could change daily traffic patterns.

CCS and others pointed out that the ESDC didn’t address congestion pricing, which could be the most significant mitigation measure, as a citywide program could change daily traffic patterns.(Congestion graphic from Battling Traffic: What New Yorkers Think about Road Pricing.)

The ESDC responded by citing a very limited concept of congestion pricing, regarding Nets games rather than an areawide policy:

In addition, congestion pricing has also been incorporated in the proposed mitigation plan in the form of a surcharge that would be imposed for on-site arena parking on game days.

NYC concurrence

CCS criticized the ESDC for not accounting sufficiently for growth in Brooklyn and its effect on the transit system:

[T]he FEIS claims the projected subway ridership by line was approved by NYC Transit, but provides no correspondence from NYC Transit indicated its concurrence, as with the City agencies, a typical requirements of FEISs.

The ESDC response does not attach correspondence:

As indicated in the FEIS, NYCT has reviewed and concurred with the transit analysis.

Konheim commented, “I think they regurgitate the responses in the FEIS response to comments, they count on nobody really looking to see if they actually answered those questions in the comments, and they brush aside the substance of comments where they don’t have a specific response by saying, ‘Oh, they were approved by the agencies.’”

Accessory parking

CCS commented that the zoning and financing for the Long Island College Hospital (LICH) garage prohibited it from being used as accessory parking on game nights.

The ESDC responded that it would all work out:

All necessary approvals for utilization of the LICH garage for remote parking would be obtained.

(Emphasis added)

Demapping streets

Urban planner Vaidila Kungys submitted numerous comments, some of which were ignored in the FEIS. After that document was issued, he further commented (3.6MB; note that the ESDC copy does not preserve his color coding) to the ESDC.

For one thing, he said that the FEIS had failed to address his comment on the demapping of streets, which he said would adversely affect traffic congestion, safety, and pollution. The ESDC responded that it had addressed the comment in the FEIS, citing Response 12-10, which explains why parts of Fifth Avenue and Pacific Street would be closed:

As discussed in the DEIS, the closures of these street segments would reduce the number of pedestrian crossing locations and the number of vehicle turning movements in the vicinity of the project site, thereby reducing the potential for vehicle/pedestrian conflicts at some locations. At other locations, however, it is acknowledged in the DEIS that the proposed project would result in an increase in vehicle and pedestrian trips and therefore an increased potential for conflicts. The traffic analyses in the DEIS account for the traffic that would be diverted as a result of these closures, and the proposed project and its traffic mitigation plan include a range of design elements and physical and operational measures to improve traffic and pedestrian flow and enhance safety.

Kungys went over that response and told me:

I believe that AKRF’s response does not accurately address my concern, which is overall safety... The claim is that by demapping streets, some locations have the potential to be made safer since cars won’t be there, but it does not explain how overall safety will be met. Why? Because, simply put, demapped streets relate to more cars driving on fewer roads thereby adding to traffic congestion, making the overall conditions less safe for pedestrians, bicyclists, and other motor vehicles.

Urban design criticism

Kungys told the ESDC:

It is likely that a drastically different environment will isolate and separate the existing neighborhood from the new neighborhood, especially considering the breaks in the street wall, and enormous heights (that will cause increased shadows), and demapped streets, which hold together the sense of connections in urban settings.

The ESDC cited its response (8-2) in the FEIS:

As stated in the DEIS in Chapter 8, “Urban Design and Visual Resources,” the proposed project’s residential blocks would establish physical and visual connections to the neighborhoods located north, south, and east of the project site. The Design Guidelines require that each of the residential buildings has a strong streetwall component... The Fort Greene street grid north of the project site would be extended physically and visually as pedestrian paths into and across the eight-acre open space component of project site... . The access points would be a minimum of 60 feet wide, comparable to the width of a neighborhood street (the east–west connections would be wider), and would be landscaped with easily identifiable streetscape elements.

Upon seeing that, Kungys commented:

Response 8-2 discusses street walls, pedestrian access points, and visual connections but does not respond to the issue that the de-mapped streets would alter the street pattern and urban design significantly. Removing over a ¼ mile of public roads destroys the urban fabric. Therefore, demapped streets would adversely affect urban design and view corridors simply because they would no longer be public streets—regardless of the benches, trees, etc. that are brought there, the demapped streets would sever the public right of ways and thereby negatively alter the urban design, visual corridors, and street patterns and street hierarchy.

Open space

Kungys criticicized the DEIS for not taking an alternative plan, which would include an arena and significantly smaller buildings, more seriously:

In 6-28 the EIS, discussing the Reduced Density Arena Alternative, states that “The pocket parks would be surrounded on three sides by new residential buildings; therefore, they may not be perceived as public parks by other residents of the community.” Nevertheless, this is not mentioned in the Chapter 6 (Open Space) for the proposed project. Why not? The DEIS fails to be consistent in methodology. If it is assumed that pocket parks surrounded on three sides may not be perceived as public parks by other residents for the Reduced Density Arena Alternative then, by the same logic, it should require the EIS to state that residents would similarly not perceive open space within the Proposed Plan as public space.

The ESDC responded:

The connective qualities of the proposed project’s open space and the deficiencies of the open space under the Reduced Density alternatives are described in Chapters 6, “Open Space and Recreational Facilities” and 20, “Alternatives,” respectively.

Kungys commented:

My comment was about the consistency of the EIS, not connective qualities relating to the project. The response failed to address my concern because the proposed project would create places just like the Reduced Density Arena Alternative’s pocket parks; it would create spaces that would not be perceived as public because they would be recessed within a private development. The EIS’s inconsistent reasoning is based on bias, not reason.

Alternatives

Kungys suggested that the Reduced Density Arena Alternative has a better park plan, criticizing the state’s statement that a park bordering heavily trafficked Atlantic Avenue would be a bad idea. He wrote:

Nevertheless, streets border many of our best parks: Bryant Park, Central Park, Fort Greene Park, Prospect Park, Union Square, Tompkins Square, Washington Square, just to name a few. The Reduced Density Arena Alternative’s park would be qualitatively better than most of the proposed project’s open space because it would clearly be public due to the fact that it would be surrounded by streets and not nestled within a private mixed-use development.

The ESDC cited Response 20-12:

The Reduced Density—Arena Alternative provides for far less public open space (1.84 acres) than the proposed project (8 acres), and it would quantitatively reduce the availability of active and passive open space as compared to the no build condition. Thus, the amount of open space proposed under the Reduced Density—Arena Alternative would be inadequate to serve the residents and workers of the study area. In addition, the open space provided under this alternative would not provide for the variety of recreational opportunities planned with the proposed project.... The portion of the open space located between Carlton and 6th Avenues would be physically adjacent to the Pacific Street and directly accessible from the sidewalk. In addition, portions of the project’s open space would directly front Atlantic, Carlton and Vanderbilt Avenues and Dean Street.

After seeing that, Kungys responded:

My comment referred to the quality of the design, not the size of the park. More isn’t always better. After all, what good is a large park if it isn’t used? Also, we need to remember that the transfer of public roads (de-mapped streets) to publicly accessible private space instantly gives the proposed project most of that 8 acres of open space.

[Actually, the streets would be a significant but not majority component.]

He continued:

Nevertheless, the Reduced Density version would maintain the existing roads and add others to bring about more publicly accessible space for walking, cycling, driving, and to provide more access to light and air. Which park would you prefer: Fort Greene Park or the grass in Stuyvesant Town?

Comments

Post a Comment