Waiting for ESD: big doubts (acc. to Real Deal) about NY State obligations attached to Greenland foreclosure sale. But how can bidders proceed if they don't know?

Credit The Real Deal and Kathryn Brenzel for being the only publication--well, besides mine--to recognize the 20-year anniversary of Atlantic Yards.

Was Forest City generous?

Was Goldstein a "holdout"?

The article states that "the final holdout, Daniel Goldstein, accepted $3 million from Forest City for his Pacific Street apartment."

And credit them, in Atlantic Yards at 20: Unfinished and facing foreclosure, for an analysis that breaks some news--though I think the framing of the project's performance is too sunny, relying on proponents like former Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz.

ESD won't comment

Crucially, Empire State Development (ESD), the gubernatorially-controlled state authority that oversees/shepherds Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, won't comment on what conditions may be attached to the auction of six development sites over the railyard next month

Will the May 2025 affordable housing deadline, with $2,000/month fines for 876 (or 877) remaining units, transfer? Will the bidder(s) also be responsible for building the platform and paying the MTA $11 million a year for development rights?

Those are major expenditures that significantly affect the value of any bid. How can any potential bidder proceed before they know whether and how they assume those obligations.

Could Gov. Kathy Hochul waive those obligations and/or commit public funds? ESD--which has ignored my queries--would only say Hochul is committed to the “successful buildout and completion of this project" and is reviewing it.

To the Real Deal, City Comptroller Brad Lander and Fifth Avenue Committee head Michelle de la Uz expressed concern that ESD would make a deal without public input. Former Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, a real estate developer herself, believes the penalties should remain. And Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso worries that it would be precedent to renege on other deals.

I'd add that the state has consistently shown an unwillingness to push the developer, so it offered a 25-year deadline on a project long professed to take ten years, and it allow for "affordable housing" to be defined as any units participating in government programs rather than broad spectrum originally promised by original developer Forest City Ratner.

Also note that--unmentioned in the article--both ESD and embattled developer Greenland USA have lost longtime staff working on Atlantic Yards

Too sunny

Why is the piece too sunny? The last word goes to former Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, who wanted a pro team to restore Brooklyn's glory and knit the borough together, and--in testimony uttered by a rep in July 2009--claimed that, when Atlantic Yards was completed, "it will serve as a model for all cities in the United States."

More likely a model of what not to do.

“The great fears, the alarms, the threats, I’m happy to say did not come to pass, at least in my opinion,” Markowitz told the publication. “Has it fulfilled every objective? It hasn’t. But it shouldn’t stop New York state from thinking big.”

OK, the arena didn't ruin the neighborhood. though operations have frustrated the nearest neighbors and little snags like escaping bass necessitated the expensive construction of the arena's noise-dampening green roof.

Earlier in the article, Markowitz justified the project by saying, “You have to understand where Brooklyn was. It was a pit. It was a railroad pit.”

Wait a sec. The MTA's Vanderbilt Yard is still a pit--two of the three blocks remain--and the removal of that purported "blight" justified the state's use of eminent domain to help Forest City Ratner assemble the project.

While the railyard was underdeveloped, the MTA had never put it out for bid. That would've been a way of developing the "pit."

Moreover, the presence of the "pit" had not deterred the conversion of adjacent former industrial buildings into condos, some of which were demolished for the project.

More news: a Greenland mismatch?

Brenzel quotes Glen as recalling a 2015 meeting in Shanghai with the chairman of the Greenland Group, the parent company of Greenland USA, which had just bought 70% of the project going forward from Forest City, excluding the arena company and the ill-fated modular tower (B2, aka 461 Dean Street).

From the article:

She remembers touring a condo sales center that pitched the dream of living in New York and being struck by how focused the firm seemed on the condo portion of the project.

Glen, who led the de Blasio administration’s housing agenda and pushed for Pacific Park’s affordable housing deadline, sensed a disconnect between the priorities of the parent company and the promises its subsidiary made to the state.

That was telling, in retrospect. I'd add that, even if Greenland expected to cross-subsidize the affordable rentals with condos, the dream of condos soon died given revisions to the 421-a tax break.

What went wrong

TRD cites local opposition and lawsuits, the recession, rising interest rates, the loss of the 421-a tax break for rentals, Forest City's modular construction gambit, and corporate challenges faced by both Forest City and Greenland.

I'd add that city and state governments were enablers and failed to vet promises, with both the developers and the governments signing on to unrealistic timelines.

I'd add that city and state governments were enablers and failed to vet promises, with both the developers and the governments signing on to unrealistic timelines.

Former Forest City CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin "recalled that Forest City made public commitments 'upfront that were long-lasting, far-reaching, formidable obligations'" that added complications, according to the article.

Those weren't enumerated, but they included moving and building the railyard, building a new subway entrance, and pledging to buy railyard development rights. Of course the latter was renegotiated and other public obligations, such as affordable housing, were attenuated in timeline and quality.

Also, I'd add (as explained below), competition from Downtown Brooklyn.

What went right, and a missed opportunity

If proponents like Markowitz and Gilmartin cite the presence and performance of the arena as a project benefit, we should recognize that the arena--despite losing money!--has turned out to be a huge business success, though not for original developer and Brooklyn Nets owner Ratner.

The presence of the arena helped vault the value of the Brooklyn Nets.

It was Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov, who bought the team and arena company from Ratner, who made a huge profit selling them to Joe Tsai.

In other words, had Ratner's publicly-owned company had the vision, and financial commitment, for a longer run with the Nets, they could've netted significant profits that would've counteracted the costs of the larger development. And the public could've/should've gotten a piece of that upside.

Only six buildings left?

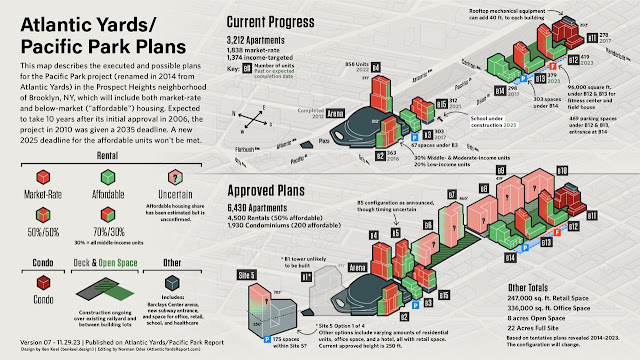

Note the statement in the article that "Nine of the planned 15 buildings are complete, but the remainder of the project is in jeopardy."

That suggests that all that's left are the six sites over the railyard.

But Greenland presumably still has development rights for Site 5, and surely wants to transfer the bulk of the unbuilt B1 (aka "Miss Brooklyn") across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5.

That plan, contemplated since 2015/2016, would require a new public approval process and, perhaps, new obligations for affordability. But it's a valuable site.

A "victim of its own success"?

It's hard to tease out, Brenzel's article suggests, how much Atlantic Yards helped transform Brooklyn, given the momentum that already existed.

But the arena did not cause the far-reaching problems some feared and didn't hamper development nearby.

Was Atlantic Yards, as the article suggests, a "victim of its own success"? Well, only in part, as developments nearby moved faster, given the lack of complicated infrastructure plans and costs.

I'd say it's more a victim of the success of the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which, though assumed to deliver new office buildings, instead brought thousands of new apartments, which caused a glut that led Forest City, in the last phase of its joint venture with Greenland, in 2016 to declare a unilateral pause on the project.

It's also worth mentioning that the Atlantic Yards plan, extending to Vanderbilt Avenue, also stimulated a wave of private spot rezonings on or near Atlantic Avenue, in what was known as the M-CROWN district. That led, belatedly, to the ongoing rezoning study known as the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use plan.

There's already a tower at the northeast corner of Atlantic and Vanderbilt, known as The Axel. (In the photo below, see the glass building center-left in the distance.)

It's the height of the much bulkier tower planned for the northeast slot in the Atlantic Yards plan, known as B10--at least if the latter ever gets built.

Was Forest City generous?

The article suggests "Forest City shelled out untold millions to buy out property owners on the adjacent parcels" to build the project.

Well, yeah, but the company was reimbursed $100 million by taxpayers.

Was Goldstein a "holdout"?

The article states that "the final holdout, Daniel Goldstein, accepted $3 million from Forest City for his Pacific Street apartment."

Actually, Goldstein had already lost title to his condo, and the settlement urged by a judge was designed to get him to leave by the developer's deadline.

Comments

Post a Comment