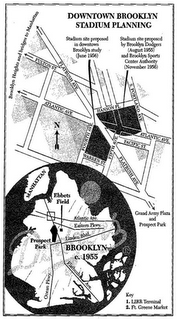

Journalists, politicians, and other commentators have readily--though incorrectly--repeated a central fudge in the Atlantic Yards saga, that the site would be the same as that proposed by Brooklyn Dodgers' owner Walter O'Malley before he moved the beloved Dodgers to Los Angeles.

Journalists, politicians, and other commentators have readily--though incorrectly--repeated a central fudge in the Atlantic Yards saga, that the site would be the same as that proposed by Brooklyn Dodgers' owner Walter O'Malley before he moved the beloved Dodgers to Los Angeles.Rather, the site would have been north of Atlantic Avenue, replacing the Long Island Rail Road terminal and the adjacent Fort Greene Meat Market, roughly the site that now includes the Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center malls.

Another potential site was below Flatbush Avenue, between Fourth Avenue and Warren Streets, thus taking out rows of now-valuable row houses. (Were these "downtown "sites? Then, perhaps. Now, the southern site, at least, would be Park Slope.)

(Graphic from Henry Fetter's book Taking on the Yankees: Winning and Losing in the Business of Baseball, which was issued before the Atlantic Yards plan was officially announced. Click to enlarge. More from Fetter below.)

An important distinction

Despite the attempt of some Atlantic Yards boosters or nostalgists to suggest that the project would fulfill, albeit with a different sport, O'Malley's long-lost dream, Atlantic Yards is a distinct product of its time, not a 50-year echo.

Despite the attempt of some Atlantic Yards boosters or nostalgists to suggest that the project would fulfill, albeit with a different sport, O'Malley's long-lost dream, Atlantic Yards is a distinct product of its time, not a 50-year echo.Yes, O'Malley's idea was to move the Dodgers near Brooklyn's busiest transit hub. But no one at the time was proposing to build over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard between Atlantic and Flatbush avenues, as with the Atlantic Yards plan above. That would’ve been too costly.

The idea of building over the railyard didn't come up for 15 years or so, with a proposed new campus for Baruch College of the City University of New York, but nothing came of it. There wasn't enough money.

Only recently, when the cost of land has risen steadily in response to the city's growth, has it become financially feasible to build platforms over railyards and highway cuts, as proposed in Mayor Mike Bloomberg's PlaNYC 2030.

Fetter's book, issued in September 2003, should have been a useful resource for anyone writing about the Dodgers stadium location, as previous books could have been. Instead, some writers and observers have perpetuated a myth.

Careful Ratner rhetoric

It's possible that Forest City Ratner peddled the "Dodgers redux" story quietly to the unquestioning press; however, in official statements, the developer has been careful and accurate in its rhetoric about the location, if not the full story of the Dodgers' departure.

For example, a press release issued 12/10/03, when the project was announced, stated: The Brooklyn Arena will sit on a three-block parcel of land at the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues--the same area where Walter O'Malley, the legendary owner of baseball's Brooklyn Dodgers, had envisioned a home for his team nearly half a century ago.

(All emphases added.)

Similarly, FCR's June/July 2005 issue of the Brooklyn Standard stated:

The Brooklyn Nets will be dribbling down the court across the street from where then-Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley wanted to build a stadium for his team.

Press errors

The New York Times got the location wrong multiple times. An 8/8/03 article, headlined YankeeNets Is on the Verge of Splitting Apart, stated:

The site, which includes a rail yard and public and private land, strikes a historical echo in Brooklyn. In the 1950's, Walter O'Malley, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, wanted to build a stadium there to replace Ebbets Field.

A 1/16/04 article, headlined Yo, Dodgers? No Way! Brooklyn Is Betting on the Nets for Revival, stated:

Coincidentally, the Nets would be based at the same site that Walter O'Malley wanted as a new home for the Dodgers before moving the team to California.

The Times, in a 1/22/04 article headlined Nets Are Sold for $300 Million, and Dream Grows in Brooklyn, maintained the error:

There is no guarantee that Mr. Ratner will be able to fulfill his vision in Brooklyn, where sports fans are still haunted by memories of the Dodgers' departure to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. The arena would be built on the same site the Dodgers were rebuffed from buying.

A 7/1/04 Times editorial, headlined The Brooklyn Nets, similarly erred:

There is also, of course, the dream of giving back to Brooklyn some of the luster it lost when Robert Moses killed Walter O'Malley's vision of building a domed stadium for the Dodgers at the same site nearly 50 years ago...

Former Brooklyn Borough Historian (!) John Manbeck, in an 11/13/05 Times op-ed headlined The Project That Ate Brooklyn, wrote:

At the core of the Atlantic Yards plan is an arena for the New Jersey Nets on the very site that was denied the Brooklyn Dodgers 50 years ago.

More recently, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (reprinted from the Cooperator) stated:

Also, the proponents of Atlantic Yards say that the rail yard area, with its access to the railroad and a plethora of subway lines, is perfect for an arena. That very site, they point out, was coveted by Dodger owner Walter O'Malley in the mid-1950s when he still was willing to build a new Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

Several Associated Press articles made the same error.

Gargano, Bloomberg, and beyond

Former Empire State Development Corporation Chairman Charles Gargano got it wrong, telling Metro on 5/17/06:

I grew up in Park Slope, and another big blunder by the city was we lost the Brooklyn Dodgers. They wanted to build a new Ebbets Field at the Atlantic Yards.

Mayor Mike Bloomberg, at the 1/18/07 Barclays naming rights press conference, erroneously claimed that the site “would have been home for the Dodgers."

Earlier, at the 5/4/04 City Council hearing regarding Atlantic Yards, Brooklynite Arthur Piccolo stated:

As a very young boy I remember the tragedy of the Dodgers leaving our Borough because.. as it is now known opposition to moving the Dodgers to the very site we are considering, forced the Dodgers to the West Coast, tearing the very soul out of Brooklyn.

There are surely other examples.

Looking back

As Fetter's definitive 2003 book Taking on the Yankees: Winning and Losing in the Business of Baseball, explains, O'Malley was playing hardball for a bigger stadium.

As Fetter's definitive 2003 book Taking on the Yankees: Winning and Losing in the Business of Baseball, explains, O'Malley was playing hardball for a bigger stadium.Ebbets Field could hold only about 32,000 fans, and Yankee Stadium, home of the hated cross-town rivals, could hold more than double that number. On the other hand, as Fetter points out, Boston’s Fenway Park, another equally antiquated and small facility, survived the calls for its demise, and remains beloved, sold out, and profitable.

Today, retro-style baseball only parks, as opposed to the multipurpose stadiums built in the 1960s and 1970s, have become the hallmark of baseball since the opening of Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore in 1992. (Indeed, the new Mets stadium in Queens is supposed to have Ebbets Field-like elements, though it likely will avoid the plethora of poles that obscured vision at the Brooklyn facility.)

Development plans

As Fetter explains, when it opened in 1913, Ebbets Field was initially most accessible not by subway but by trolley—remember, Brooklynites were once dubbed “Trolley Dodgers,” hence the team’s name—and it was built at the fringes of development. By the 1950s, however, there was too little parking, the stadium was small, and the neighborhood was “changing,” as some gingerly pronounced, thus deterring some longtime fans.

As for O'Malley's plan, writes Fetter:

It was an audacious decision, entirely at odds with the history of ballpark construction in New York City. Each in their turn—the Giants under Brush, the Dodgers under Ebbets, the Yankees under Ruppert—had been driven, by the price of land and the accelerating congestion of urban life, farther and father toward the margins of the city in order to find land cheap enough and extensive enough to build a ball park. O’Malley proposed to break that pattern and return baseball to the central city.

But O'Malley wanted a lot of help:

The only way to obtain sufficient contiguous acreage for the stadium in that area, and to divest existing owners and users at an affordable price, was by resorting to the sovereign power of condemnation. “Of course,” lawyer O’Malley knew, “The ball club very properly does not have the legal right to condemn land.” His solution to that potential obstacle was to link the construction of a new Dodger stadium to a comprehensive plan for the redevelopment of the entire surrounding neighborhood, so that the eminent-domain powers of the sovereign city could be made to serve the real estate demands of his Dodgers.

The project could relocate the Fort Greene meat market (now the site of the Atlantic Center mall and environs), build a new Long Island Rail Road terminal, add parking and eliminate a “traffic intersection that was terrible.” (The solution for the latter isn’t clear from the book.)

Money questions

The problem was that O’Malley wanted the land at about a 90 percent discount, and the site improvements would be costly, too. The city would end up paying $40 million of a $55 million plan, even though O’Malley would build the stadium himself, according to Fetter.

O’Malley tried to enlist Robert Moses to use federal slum clearance funds aimed at housing, but Moses said a ballpark plan “cannot be dressed up as a Title I project.”

While O’Malley compared the Dodgers’ attendance with that of rivals in newer stadiums, Fetter points out that the Dodgers posted numbers “that remained among the highest in baseball” and that Brooklyn had a trump card most rivals lacked; huge television and radio revenue in a large media market. The Dodgers, he reports, were actually the most profitable team in baseball.

Public opposition

Despite the immense nostalgia for the Dodgers exhibited by Brooklynites of a certain vintage, most city leaders, and the public, though not Borough President John Cashmore, actually opposed O'Malley's demands. Even City Council President Abe Stark, the former Brooklyn Borough President who was first famous for his "Hit Sign, Win Suit" sign at Ebbets Field, opposed "the cold war of silence and evasion" practiced by Dodger management.

Observes Fetter:

It was not a proposal calculated to gain the approval of city officials struggling to proceed with a backlog of Depression- and war-deferred projects, and facing an overwhelming array of social-service and educational demands on public monies.

In 1956, a new Brooklyn Sports Center Authority proposed another site, across Flatbush from the railroad terminal, down to Warren Street in Park Slope. However, that was a nonstarter; it would have demolished hundreds of units of housing without creating new housing. So the authority returned to the plan at the terminal.

So, notwithstanding those, as with the Times editorial, who blame Moses for "killing" O'Malley's vision, the responsibility was far broader. Fetter notes:

The key to O’Malley’s’ failure was that Moses was hardly alone in opposing O’Malley’s stadium project. There was simply no significant political support for a public subsidy for a privately owned stadium operated by a profit-making enterprise.

Nor was downtown Brooklyn a sensible ballpark location at the time. The demand for driving was high, but there would be parking for only 2500 cars. The location was hard to reach by car, with no highway within a mile of the site. It would exacerbate congestion, Fetter writes, and provide no impetus to rehabilitate the neighborhood.

Going to L.A.

In the Brooklyn Standard article referenced above, the writer for Forest City Ratner's "publication" cited the conventional wisdom that the city's unwillingness to accommodate O'Malley lost the Dodgers:

The blocking of that plan directly resulted in O’Malley’s decision to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles, leaving Brooklyn without a major sports team of its own ever since.

The reality was a little more complicated, as Fetter's book explains. O’Malley stood firm in wanting massive subsidies; he wasn’t willing to move even to Queens. Growing Los Angeles, hungry to be a big league city, had its wallet open for him.

The Dodgers wanted “to build the ballpark we want in the location we want,” as O’Malley put it. Today, Borough President Marty Markowitz’s rhetoric offers an eerie echo: It is well-known that I believe Atlantic Yards is the right project at the right time in the right place for Brooklyn.

1957 vs. 2007

There are some significant differences between O'Malley's plan and Forest City Ratner's plan, ones that make the latter's plan more palatable to some. A baseball stadium would draw larger crowds and operate seasonally; an arena would draw half as many people (or fewer) and operate all year round, thus creating more activity in the area.

Then the car was overtaking mass transit; now cars are even more popular, but a new emphasis on mass transit is crucial to survival of the city.

The Atlantic Yards plan, unlike the Dodgers stadium plan, would include a significant amount of housing, as well as transportation and infrastructure improvements, which, along with the arena, constitute a "civic project," state officials say. (That's contested in court.)

Forest City Ratner has found a way to respond to some of the criticisms of the plan 50 years earlier. The project would develop undeveloped land, though, arguably, it's not the only way to rehabilitate the neighborhood. But the traffic problems envisioned 50 years ago remain and the building of extremely dense housing threatens to tax the infrastructure.

Another important difference is that, since the 1960s, residents of adjacent neighborhoods like Park Slope, Boerum Hill, and Fort Greene have invested--initially with little help from banks or the government--in their neighborhoods, helping create the "Brooklyn renaissance" that makes the Atlantic Yards site "a great piece of real estate," in the words of Forest City Enterprises executive Chuck Ratner.

Forest City Ratner lined up significant political support before it publicly announced the Atlantic Yards plan. And these days most cities, not just newly growing ones like Los Angeles in the 1950s, are now willing to subsidize a privately owned sports facility operated by a profit-making enterprise, as Fetter noted at a conference in March.

(Note: the Brooklyn Arena technically would be owned by a state subsidiary that would lease it to Forest City Ratner for $1. And the developer has already sold naming rights to Barclays Capital as part of a reported $400 million package.)

Other books

In March 2005, Lumi Rolley of No Land Grab cited Roger Kahn's book The Boys of Summer, which pointed to the location "along Atlantic Avenue [where] wholesale meat markets led toward slums."

In May 2006, I had cited Michael Shapiro's book The Last Good Season (p. 42) which focused on meat market location as well.

Neither book offers as comprehensive an explanation as does Fetter, but the basic point is clear: O'Malley wanted land north of Atlantic Avenue--land that in five years would be part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area--not the Vanderbilt Yard.

The press and politicians should have been paying attention.

An arena site

The railyard site was, however, discussed as a potential arena site 17 years after the Dodgers left Brooklyn. As noted last August, the Draft Environmenal Impact Statement (DEIS) cites a 1974 city-sponsored preliminary feasibility study for the Brooklyn Sports Complex, a 15,000-seat arena.

Of the five downtown sites considered, plus Fulton Ferry, only two appeared to meet the key criteria for size and accessibility. Both sites were listed in ATURA. One is the current site of the Bank of New York Tower and the two shopping centers: Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal. The other is the site currently being proposed for the Atlantic Yards Arena. In the 1974 report, the arena site extended from the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues eastward along Atlantic Avenue to Carlton Avenue. The site extended southward along Flatbush Avenue to Dean Street, continued eastward to 6th Avenue, then northward to Pacific Street and eastward to Carlton Avenue. In short, the site encompassed the arena block and Block 1120.

Of the five downtown sites considered, plus Fulton Ferry, only two appeared to meet the key criteria for size and accessibility. Both sites were listed in ATURA. One is the current site of the Bank of New York Tower and the two shopping centers: Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal. The other is the site currently being proposed for the Atlantic Yards Arena. In the 1974 report, the arena site extended from the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues eastward along Atlantic Avenue to Carlton Avenue. The site extended southward along Flatbush Avenue to Dean Street, continued eastward to 6th Avenue, then northward to Pacific Street and eastward to Carlton Avenue. In short, the site encompassed the arena block and Block 1120.Note that the first of the two sites mentioned above was the site O'Malley sought.

The 9.5-acre site (above, outlined in red) proposed in 1974 for the sports complex is not the same as the 22-acre site proposed for the Atlantic Yards project, which would incorporate two large blocks east of Carlton Avenue to Vanderbilt Avenue, and also encompass the streetbed of Pacific Street. The project also would include a rectangle of land 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue between Pacific and Dean streets, as well as Site 5, the wedge west of Flatbush Avenue where it meets Atlantic and Fourth avenues, and Pacific Street.

Comments

Post a Comment