After an initial column praising Atlantic Yards, New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff in June 2006 wrote a more pensive if hardly tough assessment of the project, taking up the cause of architect Frank Gehry, lamenting his lack of sway with developer Bruce Ratner and the failure of the government to plan for open space.

Six months ago, Ouroussoff was predicting a redesign for Phase One of Atlantic Yards, one that would reveal whether “Brooklyn will receive a dazzling 21st-century version of Rockefeller Center.” It never emerged.

Now that financing troubles (and more) have slowed the project significantly, reducing it to an arena at first, Ouroussoff has written something of an elegy, urging Gehry to leave the project, predicting blight (!), and even seeming to emerge as a project opponent.

Gehry’s vision

Ouroussoff’s essay, headlined What Will Be Left of Gehry’s Vision for Brooklyn?, begins:

The growing possibility that much of the multibillion-dollar Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn will be scrapped because of a lack of financing may be a bitter pill for its developer, Forest City Ratner. But it’s also a painful setback for urban planning in New York.

The growing possibility that much of the multibillion-dollar Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn will be scrapped because of a lack of financing may be a bitter pill for its developer, Forest City Ratner. But it’s also a painful setback for urban planning in New York.

No, it may be a painful setback for ambitious architecture and even a painful setback for the model of an arena wrapped in towers to buffer its impact. But it’s not a painful setback for urban planning because there was no real urban planning, no RFP for the site as a whole, no competition, no meaningful public input.

That’s why the Municipal Art Society’s Kent Barwick suggested that AY might be this generation’s Penn Station: “Maybe the absurdity with which that proceeded will awaken the desire for a more rational process.”

Gehry’s vision for Brooklyn, however honorable an attempt to negotiate some serious challenges, also has been accompanied by a disdain for the public--wisecracking how opponents “would’ve picketed Henry Ford”--and disregard for the tactics of Bruce Ratner, a fellow “do-gooder, liberal.”

Urban blight

Ouroussoff writes:

Designed by Frank Gehry, the project was a rare instance in which the architectural talent lined up for a New York project matched the financial muscle behind it. When it was unveiled in late 2003, it seemed to signal a genuine effort to raise the quality of large-scale development in a city still stinging from the planning failures at ground zero.

So if the decision to proceed with an 18,000-seat basketball arena but to defer or eliminate the four surrounding towers is defensible from a business perspective, it also feels like a betrayal of the public trust.

Mr. Gehry conceived of this bold ensemble of buildings as a self-contained composition — an urban Gesamtkunstwerk — not as a collection of independent structures. Postpone the towers and expose the stadium, and it becomes a piece of urban blight — a black hole at a crucial crossroads of the city’s physical history. If this is what we’re ultimately left with, it will only confirm our darkest suspicions about the cynical calculations underlying New York real estate deals.

There is a good argument for wrapping an arena in towers to deflect its impact, but there’s also a question of whether those towers, two of them abutting a street with row houses, were way too big.

Ouroussoff says he sympathized with the arguments of critics but also thought “Atlantic Yards presented a creative opportunity for the 21st century,” an opportunity to “enlist serious talents like Mr. Gehry.”

Street grid?

Ouroussoff somehow forgets about the superblock:

Ouroussoff somehow forgets about the superblock:

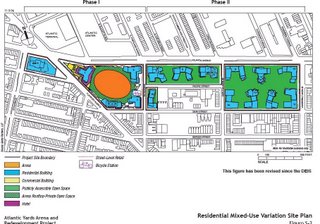

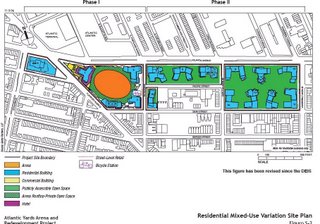

As it turned out, Mr. Gehry’s design revealed both the promise and the limits of that collaboration. The main residential blocks to the east of the arena lacked the architect’s signature ebullience. A series of mismatched towers along two sides of a central courtyard encompassing several blocks, they followed most of the usual planning rules: adhere to the street grid, pack in a good deal of retail along the street, add a dose of public space.

Actually, the design would adhere to the street grid only along the perimeter; Pacific Street would be demapped to create a superblock and maintain the open space ratio.

The arena block

Ouroussoff rhapsodizes about the arena block, given that the arena would be wrapped in towers. Except he calls Miss Brooklyn “glamorous” and describes “[t]hree smaller residential towers” without acknowledging they’d be 30-50 stories, a jolt to the scale of Prospect Heights.

Still, his description of an “imaginative fusion of inside and out” and “a multitiered glass atrium” sound seductive.

Signs of trouble?

Ouroussoff writes:

The first sign that something was amiss arose when Forest City began to reduce the percentage of affordable housing units in the design and add condominiums, decisions that altered the project’s character. Then the developer quietly asked Mr. Gehry to redesign Miss Brooklyn to cut costs. The delirious exterior was replaced by a less graceful design, with floors piled loosely on top of one another, their forms twisting as they rose. The atrium was reduced to an empty glass hall with a set of bleachers overlooking the street.

Actually, the change in affordable housing was defended to the hilt by the developer and taken as gospel by the Times.

Eyesore coming

Ouroussoff gets forceful:

Without the towers the arena is likely to become an enormous eyesore. Even if Mr. Gehry adorns it with a seductive new wrapper, its looming presence will have a deadening impact on a lively area. The magical peekaboo effect of peering between the bases of the towers into the arena will be lost. The atrium, once a vital public space, will be reduced to a barren strip of pavement.

Well, project defenders might say, the patchwork of empty lots right now isn’t so lively. And critics might say: wasn’t the atrium, the Urban Room, part of the transit improvements cited by the Empire State Development Corporation in approving the project?

Joining the opposition?

While the presence of empty lots generates a pressure to build something, Ouroussoff isn’t taking the bait:

No development at all would be preferable to building the design that is now on the table. What’s maddening is how few options opponents seem to have.

Here he shifts voice and suggests that he is among “opponents,” while, more likely, he’s an opponent of Gehry’s vision being stymied:

We could wage a public campaign to stop it. We could pray that Forest City Ratner comes up with more money. But given that the city approved the plan, we cannot prevent the developer from building the arena. Nor is there any way of preventing Forest City from selling off pieces of the property to other investors, who could then come up with any design they liked, as long as they abided by zoning and density guidelines.

The city did not approve the plan. The state did, with design guidelines but overriding zoning and density guidelines. And, given that financing documents haven’t been signed, there may indeed be political leverage.

[Update: And, as DDDB suggests, what do you mean "we," given that there has been a fierce fight for more than four years.]

Walking away

Ouroussoff, again thinking of the architect, suggests that Gehry could leave the project:

Mr. Gehry, on the other hand, could walk away.

In the old days, when he was still a budding talent with an uncertain future, he walked off jobs when a client began pushing things in the wrong direction. This was not simply an act of vanity; it showed that the quality of his work mattered more to him than a paycheck.

Years later, he has been backed into a familiar corner. There’s much more money at stake here, and I expect that he is torn between a sense of loyalty to his client and a desire to make good architecture.

But by pulling out he would be expressing a simple truth: At this point the Atlantic Yards development has nothing to do with the project that New Yorkers were promised. Nor does it rise to the standards Mr. Gehry has set for himself during a remarkable career.

The question is whether it ever did. More than two years ago, Gehry said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away.”

Maybe Forest City Ratner should release the gag on Gehry and let him talk to Brooklynites about how the project fits with his principles.

Six months ago, Ouroussoff was predicting a redesign for Phase One of Atlantic Yards, one that would reveal whether “Brooklyn will receive a dazzling 21st-century version of Rockefeller Center.” It never emerged.

Now that financing troubles (and more) have slowed the project significantly, reducing it to an arena at first, Ouroussoff has written something of an elegy, urging Gehry to leave the project, predicting blight (!), and even seeming to emerge as a project opponent.

Gehry’s vision

Ouroussoff’s essay, headlined What Will Be Left of Gehry’s Vision for Brooklyn?, begins:

The growing possibility that much of the multibillion-dollar Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn will be scrapped because of a lack of financing may be a bitter pill for its developer, Forest City Ratner. But it’s also a painful setback for urban planning in New York.

The growing possibility that much of the multibillion-dollar Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn will be scrapped because of a lack of financing may be a bitter pill for its developer, Forest City Ratner. But it’s also a painful setback for urban planning in New York.No, it may be a painful setback for ambitious architecture and even a painful setback for the model of an arena wrapped in towers to buffer its impact. But it’s not a painful setback for urban planning because there was no real urban planning, no RFP for the site as a whole, no competition, no meaningful public input.

That’s why the Municipal Art Society’s Kent Barwick suggested that AY might be this generation’s Penn Station: “Maybe the absurdity with which that proceeded will awaken the desire for a more rational process.”

Gehry’s vision for Brooklyn, however honorable an attempt to negotiate some serious challenges, also has been accompanied by a disdain for the public--wisecracking how opponents “would’ve picketed Henry Ford”--and disregard for the tactics of Bruce Ratner, a fellow “do-gooder, liberal.”

Urban blight

Ouroussoff writes:

Designed by Frank Gehry, the project was a rare instance in which the architectural talent lined up for a New York project matched the financial muscle behind it. When it was unveiled in late 2003, it seemed to signal a genuine effort to raise the quality of large-scale development in a city still stinging from the planning failures at ground zero.

So if the decision to proceed with an 18,000-seat basketball arena but to defer or eliminate the four surrounding towers is defensible from a business perspective, it also feels like a betrayal of the public trust.

Mr. Gehry conceived of this bold ensemble of buildings as a self-contained composition — an urban Gesamtkunstwerk — not as a collection of independent structures. Postpone the towers and expose the stadium, and it becomes a piece of urban blight — a black hole at a crucial crossroads of the city’s physical history. If this is what we’re ultimately left with, it will only confirm our darkest suspicions about the cynical calculations underlying New York real estate deals.

There is a good argument for wrapping an arena in towers to deflect its impact, but there’s also a question of whether those towers, two of them abutting a street with row houses, were way too big.

Ouroussoff says he sympathized with the arguments of critics but also thought “Atlantic Yards presented a creative opportunity for the 21st century,” an opportunity to “enlist serious talents like Mr. Gehry.”

Street grid?

Ouroussoff somehow forgets about the superblock:

Ouroussoff somehow forgets about the superblock:As it turned out, Mr. Gehry’s design revealed both the promise and the limits of that collaboration. The main residential blocks to the east of the arena lacked the architect’s signature ebullience. A series of mismatched towers along two sides of a central courtyard encompassing several blocks, they followed most of the usual planning rules: adhere to the street grid, pack in a good deal of retail along the street, add a dose of public space.

Actually, the design would adhere to the street grid only along the perimeter; Pacific Street would be demapped to create a superblock and maintain the open space ratio.

The arena block

Ouroussoff rhapsodizes about the arena block, given that the arena would be wrapped in towers. Except he calls Miss Brooklyn “glamorous” and describes “[t]hree smaller residential towers” without acknowledging they’d be 30-50 stories, a jolt to the scale of Prospect Heights.

Still, his description of an “imaginative fusion of inside and out” and “a multitiered glass atrium” sound seductive.

Signs of trouble?

Ouroussoff writes:

The first sign that something was amiss arose when Forest City began to reduce the percentage of affordable housing units in the design and add condominiums, decisions that altered the project’s character. Then the developer quietly asked Mr. Gehry to redesign Miss Brooklyn to cut costs. The delirious exterior was replaced by a less graceful design, with floors piled loosely on top of one another, their forms twisting as they rose. The atrium was reduced to an empty glass hall with a set of bleachers overlooking the street.

Actually, the change in affordable housing was defended to the hilt by the developer and taken as gospel by the Times.

Eyesore coming

Ouroussoff gets forceful:

Without the towers the arena is likely to become an enormous eyesore. Even if Mr. Gehry adorns it with a seductive new wrapper, its looming presence will have a deadening impact on a lively area. The magical peekaboo effect of peering between the bases of the towers into the arena will be lost. The atrium, once a vital public space, will be reduced to a barren strip of pavement.

Well, project defenders might say, the patchwork of empty lots right now isn’t so lively. And critics might say: wasn’t the atrium, the Urban Room, part of the transit improvements cited by the Empire State Development Corporation in approving the project?

Joining the opposition?

While the presence of empty lots generates a pressure to build something, Ouroussoff isn’t taking the bait:

No development at all would be preferable to building the design that is now on the table. What’s maddening is how few options opponents seem to have.

Here he shifts voice and suggests that he is among “opponents,” while, more likely, he’s an opponent of Gehry’s vision being stymied:

We could wage a public campaign to stop it. We could pray that Forest City Ratner comes up with more money. But given that the city approved the plan, we cannot prevent the developer from building the arena. Nor is there any way of preventing Forest City from selling off pieces of the property to other investors, who could then come up with any design they liked, as long as they abided by zoning and density guidelines.

The city did not approve the plan. The state did, with design guidelines but overriding zoning and density guidelines. And, given that financing documents haven’t been signed, there may indeed be political leverage.

[Update: And, as DDDB suggests, what do you mean "we," given that there has been a fierce fight for more than four years.]

Walking away

Ouroussoff, again thinking of the architect, suggests that Gehry could leave the project:

Mr. Gehry, on the other hand, could walk away.

In the old days, when he was still a budding talent with an uncertain future, he walked off jobs when a client began pushing things in the wrong direction. This was not simply an act of vanity; it showed that the quality of his work mattered more to him than a paycheck.

Years later, he has been backed into a familiar corner. There’s much more money at stake here, and I expect that he is torn between a sense of loyalty to his client and a desire to make good architecture.

But by pulling out he would be expressing a simple truth: At this point the Atlantic Yards development has nothing to do with the project that New Yorkers were promised. Nor does it rise to the standards Mr. Gehry has set for himself during a remarkable career.

The question is whether it ever did. More than two years ago, Gehry said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away.”

Maybe Forest City Ratner should release the gag on Gehry and let him talk to Brooklynites about how the project fits with his principles.

Comments

Post a Comment