Plaintiffs appealing the dismissal of the Atlantic Yards eminent domain case this morning encountered an engaged but skeptical panel of three Second Circuit appellate court judges, who let the argument extend for an hour—well more than the initial time allotted—as more than 60 people looked on in the Lower Manhattan courtroom.

The plaintiffs—*13 residential and commercial tenants and property owners—are challenging U.S. District Judge Nicholas Garaufis’s dismissal of the case, as he ruled that the public purposes associated with the project—among them subsidized housing, blight removal, new transit facilities, and a sports facility—trumped any inquiry into the legitimacy of the sequence.

[Update: *To clarify: there were 13 original plaintiffs. Two have been said to drop out but have not done so additionally. One additional plaintiff has been added when a separate suit was consolidated. So there are currently 14, and likely 12.]

Then again, they gave plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff (right) a lot of time to explain his argument that the sequence behind Atlantic Yards—in which the project was promised to a private developer without any other bids—differed from that in the cases the Supreme Court had upheld eminent domain, and that Garaufis's ruling should be reversed so the case can actually go forward.

Then again, they gave plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff (right) a lot of time to explain his argument that the sequence behind Atlantic Yards—in which the project was promised to a private developer without any other bids—differed from that in the cases the Supreme Court had upheld eminent domain, and that Garaufis's ruling should be reversed so the case can actually go forward.

(The Supreme Court’s 2005 Kelo v. New London decision upheld eminent domain because the city “carefully formulated a development plan.” and Justice Anthony Kennedy’s non-binding concurrence gave specific examples, including “evidence that respondents reviewed a variety of development plans and chose a private developer from a group of applicants rather than picking out a particular transferee beforehand,” not present in the Brooklyn case.)

Later, when he answered questions outside the courtroom Brinckerhoff brought up the obvious comparison: the ongoing bid process for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Hudson Yards, in which several developers are competing.

And while the judges did not press attorney Preeta Bansal (right), representing the Empire State Development Corporation and other defendants, as closely as they did Brinckerhoff, they did question her somewhat startling contention that, even if there were illicit motive in the case, as long as the project results in some public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” (The other defendants include Mayor Mike Bloomberg, former Gov. George Pataki, and Forest City Ratner.)

And while the judges did not press attorney Preeta Bansal (right), representing the Empire State Development Corporation and other defendants, as closely as they did Brinckerhoff, they did question her somewhat startling contention that, even if there were illicit motive in the case, as long as the project results in some public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” (The other defendants include Mayor Mike Bloomberg, former Gov. George Pataki, and Forest City Ratner.)

(Here's the Times's blog coverage and print coverage. Here's the Observer, the Sun, AM NY, AP, and NY 1.)

A non-recusal

As the day’s proceedings began, and before the two oral arguments that proceeded Goldstein v. Pataki, Judge Edward Korman, a district judge sitting on the appellate court, announced that he had received an Atlantic Yards mailer “some years ago” and responded in the affirmative. (It’s not clear what mailing he got, but it could have been this May 2004 flier. Click to enlarge.)

As the day’s proceedings began, and before the two oral arguments that proceeded Goldstein v. Pataki, Judge Edward Korman, a district judge sitting on the appellate court, announced that he had received an Atlantic Yards mailer “some years ago” and responded in the affirmative. (It’s not clear what mailing he got, but it could have been this May 2004 flier. Click to enlarge.)

The plaintiffs made no move to ask Korman, a distinguished jurist, to recuse himself, but as the argument wore on and Korman asked some tough questions, they might have had second thoughts.

Leading off

Brinckerhoff didn’t get far before he was interrupted by Judge Robert A. Katzmann, who suggested that Atlantic Yards would include “classic cases of direct public use,” cited in Kelo, “that would foreclose much of your argument.”

Brinckerhoff responded that, in this case, the blight determination was made years after the decision to have Forest City Ratner develop this project.

Korman asked if there was “any dispute” that 62% of the project site was blighted, the land from the north side of Pacific Street that encompasses the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA. (It established in 1968 during very different times, but reaffirmed ten times, most recently in 2004.)

Korman asked if there was “any dispute” that 62% of the project site was blighted, the land from the north side of Pacific Street that encompasses the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA. (It established in 1968 during very different times, but reaffirmed ten times, most recently in 2004.)

Brinckerhoff pointed out that his clients’ properties are all outside ATURA.

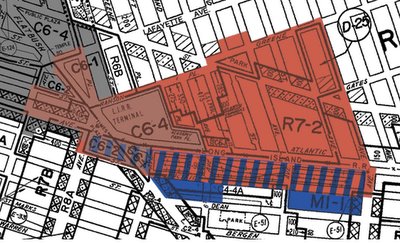

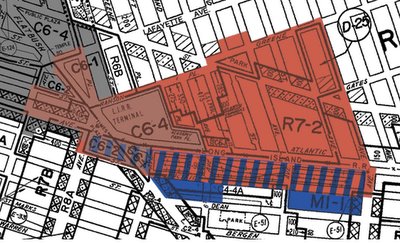

[They’re on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street. In the map, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.]

“Does that matter?” Katzmann asked. “Does there have to be a lot-by-lot determination?”

Brinckerhoff said no, as long as the sequence was legitimate. In the Supreme Court's Berman v. Parker case, he pointed out, the circumstances were “radically different,” as a legislative finding that the area was in need of renewal was followed by a request for proposals.

He said that in this case, there was no legislative determination, citing the role of the ESDC, an “unelected body.”

Korman cut him off, asking how this affected the question of public use or public purpose.

“It lessens the deference owed to decision makers,” Brinckerhoff replied.

Korman asked how the ESDC differed from other administrative agencies to which elected officials delegate certain powers.

Brinckerhoff pointed to a case involving Amtrak in which a court said a lesser amount of deference was warranted.

“The sequence gives a powerful inference,” he said, “that the taking was motivated to benefit a specific developer.” Forest City Ratner was the only developer considered, he said, and the “post-hoc” blight study concerned only the footprint that Forest City Ratner had identified.

Private motive?

“If there are public uses to be had, what different does it make that an individual has a private, self-interested motive?” Katzmann asked.

Brinckerhoff responded with a hypothetical, a government use of eminent domain for a public park, in which most of the site actually benefited the private developer.

The circumstances, he said, were like Aaron v. Target Corp., a Missouri case in which officials from Target told a city official they’d abandon the store unless they got new property through eminent domain; Target was designated as the city’s “chosen redeveloper only days after soliciting alternatives from the public.”

Korman was skeptical. “In your hypothetical, the other use has nothing to do with the park. In this instance, the property taken is directly related to the property as a whole.” He asked if Brinckerhoff would question a case in which the city took the Atlantic Yards site for its own use.

Brinckerhoff agreed that, if a government entity had followed proper procedures, it would be OK.

“The city’s purpose,” Korman pressed on, “is to derive all the benefits. They have concluded, for whatever reason, these defendants are the best suited to carry it out. Does that taint the process?”

Brinckerhoff pointed to a recent case, with “not as compelling” facts, in which a court refused to dismiss a case in which the sole allegation was that the decision to take property was made after the developer was chosen.

Why would that affect the outcome, Korman asked.

The government, Brinckerhoff said, should maximize its benefits.

Katzmann asked whether a New York case called Brody v. Port Chester dealt with the procedural issues.

Brinckerhoff agreed that the procedures in this case were consistent with the state’s eminent domain law. However, he suggested there was far greater transparency in the Kelo case, which involved a seven-day bench trial.

Corruption question

Katzmann asked if there was any specific relationship between the developer and public officials.

Brinckerhoff noted that former Gov. George Pataki, a defendant, went to law school with Bruce Ratner, that Ratner was known as a past contributor to Pataki, and there were reports that they were friends.

(A 12/10/03 Ratner profile in the New York Sun stated: Since 1986, the registered Democrat has donated almost $30,000 to local politicians, and since 2000, companies he controlled donated $7,500 to state groups affiliated with Governor Pataki.)

Beyond that, he said, there was no need for evidence of a quid pro quo, just the circumstances. In Target, he said, “the motive was that [the officials] wanted to keep Target in the community,” but Target selected the property and the government followed its lead.

How much discovery?

The plaintiffs’ goals are merely to proceed with discovery, to gain pre-trial information through documents, depositions, and interrogatories

Katzmann asked how much discovery the plaintiffs sought. Brinckerhoff was cautious, as if not wanting to suggest a fishing expedition. “Presumably rather limited,” he said.

Katzmann asked what the plaintiffs want to find out.

“To explain these anomalies” regarding the sequence, Brinckerhoff said. He suggested “some limited depositions,” noting that there’s already a limit of seven according to the federal rules.

Korman asked Brinckerhoff what, in the best case scenario, he wished to find.

“There’s every possibility,” Brinckerhoff responded, that there are documents “that make it clear the government was uninterested” in other developers and projects, and that the governor and mayor had relationships with Bruce Ratner that led them to favor him."

Korman asked what was wrong with the officials thinking that Ratner’s done good work and would do a good job on this project. (Brinckerhoff responded, but my notes are fuzzy.)

The city's motive

(As for the city's motive, part of it was answered by Andrew Alper, then president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, who testified at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing:

This particular project came to us. We were not out soliciting, we were developing a Downtown Brooklyn Plan, but we were not out soliciting a professional sports franchise for Downtown Brooklyn.

The developer came to us with what we thought was actually a very clever plan. It is not only bringing a sports team back to Brooklyn, but to do it in a way that provided dramatic economic development catalyst in terms of housing, retail, commercial jobs, construction jobs, permanent jobs.

So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and find to try to a better deal. I think that would discourage developers from coming to us, if every time they came to us we went out and tried to shop their idea to somebody else. So we are actively shopping, but not for another sports arena franchise for Brooklyn.)

Sports facility public?

Brinckerhoff soon got his steam back, arguing that “the notion that a stadium is a public use is just wrong.” (Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in her Kelo dissent identified a stadium as a public use, but without any citations.) “A stadium is a private, money-making enterprise,” he said, not different from a hotel that offers public access.

Korman brought up the example of Yankee Stadium, where municipal officials, “rightly or wrongly,” believe “there’s a significant benefit” to having a baseball team. He noted that the city would condemn property for a new Metro North station to serve the Yankees.

Brinckerhoff said it depended on the process, but noted “it’s widely understood that stadiums are money-losing enterprises.”

Courts step in?

“Is that something a court should ascertain?” Katzmann asked, nothing that certain issues are reserved for the political process.

Brinckerhoff said the case involved many claims, not just one.

Katzmann acknowledged that courts might want to say something “about the wisdom of a policy, but we’re constrained.”

Brinckerhoff reminded him that courts play a role in policing eminent domain when it seems to be motivated to benefit a specific private individual. “There’s no explanation,” he said, for why the MTA, shortly after the project was announced, said that the property was going to go to Forest City Ratner, before later issuing an RFP.

Korman wondered whether the plaintiffs would object to the exact same project if it has resulted from a more fair process, bidding in response to an RFP.

Had a government entity, Brinckerhoff said, decided through a legitimate process that the project was in the public interest, including before the private beneficiary was known, it could be acceptable. (It wasn't clear if he was acknowledging weakness in the plaintiffs’ argument that the public benefit, in terms of actual affordable housing, new tax revenues, etc., would be far lower than the government claims.)

“We have this area in Downtown Brooklyn,” Korman said, making the common error of not locating the project in Prospect Heights. “Somebody submits a proposal similar to Ratner. It goes through the hoops…” What if it benefits a private party?

“That in itself is not a problem,” Brinckerhoff responded. “It’s when the private party has driven the process.”

But what about a mixed motive, Korman asked, to benefit the public and the developer? (That's a reading of the Alper testimony.)

The previous cases, Brinckerhoff responded, differ significantly in the sequence: “All we’re asking for is that this case can be remanded so the public can know this particular decision was legitimate.”

Defense case

Bansal, arguing for the defense, declared “the analysis of this matter begins and ends with Kelo,” contending that the “multiple public purposes” made it an open and shut case.

What about the “post-hoc” blight study to which Brinckerhoff alluded, asked Katzmann.

Bansal focused on the ATURA designation, renewed in 2004. “It’s undisputed that the project would alleviate blight” in 63% of the site. “That is enough to basically end the case,” she said.

Citing the benefits, she noted that it would “create a publicly-owned sports arena.”

Publicly-owned?, asked Katzmann.

“And then leased” to a private entity, Bansal acknowledged.

“And then leased” to a private entity, Bansal acknowledged.

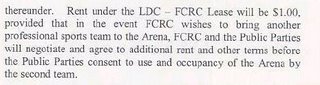

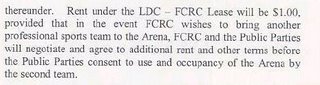

Several people in the crowd snickered, knowing that the lease would be for $1. (See the 2/18/05 Memorandum of Understanding between the city, state, and developer.)

She cited the planned Urban Room, “a nice entrance to the subway” and transit improvements “that Brooklyn has been trying to do for decades.” The MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard was “in desperate need of modernization.” (Still, there’s been no testimony that the MTA or “Brooklyn” had either of these on a publicly announced wish list.)

The seven acres of public space (actually, eight), she said, will connect neighborhoods that are separated. (BrooklynSpeaks disagrees.)

“What if the process is tainted?” Katzmann asked.

The constitutional analysis, Bansal said, does not depend on the sequence.

“It’s not just the sequence,” Korman continued, saying Brinckerhoff “relies on all these shortcuts,” including “evidence of a preconceived plan.”

Illicit motive OK

Bansal then gave a hypothetical worst-case scenario in which a smoking-gun memo or video showed that a public official stated, “I want to do this for Bruce Ratner.”

It would not make a difference. “The fact that there might be illicit motive,” she said, even if it’s the principal motive, if it results in public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” She said the issue was whether public officials could have rationally concluded there was some public purpose.

(It was reminiscent of her colleague Douglas Kraus's comment at a hearing in February that if Brinckerhoff's "clients or if other members of the community think this was really a terrible project, they can express themselves in the next election.")

Katzmann tried to drill down to an inflection point. What if an area was 20% blighted, or 50%, or 80%--how much blight would be needed to assume that decision makers acted rationally?

There’s no clear line of demarcation, Bansal said, suggesting the court’s inquiry would be “fact-specific. But we’re not close,” given the ATURA finding. “I don’t think this case is anywhere near the line.”

Judge Debra Ann Livingston, who had asked only a few questions, also pressed toward the inflection point. A court faced with procedural irregularities, she said, and just one acre of public space, would look further.

Bansal pointed to Kennedy’s Kelo concurrence, arguing that, while certain kinds of cases based on eminent domain for economic development cases may suggest pretext, there’s “nothing close to that here, given the multiple public purposes.” (The plaintiffs argue that Kelo speaks to cases beyond economic development.)

Developer-driven projects OK?

With respect to the sequence, she added, the “New York legislature has made a considered judgment that private enterprise-initiated projects… are to be favored.”

(Actually, when the Urban Development Corporation was established in 1968 the effort to encourage "maximum" private participation in project was hardly focused on developments like Atlantic Yards, but instead intended to get the private sector to finally invest in the low- and middle-income subsidized housing.)

Few developers can do these kinds of projects, she added, somehow missing the Hudson Yards example. “The fact that a private developer came to the city is of no constitutional moment.”

“Your adversary,” Katzmann said, suggested that other developers could have done it for less money, and were not considered.

That, Bansal declared, was not a federal issue. “Perhaps they have a claim under state law.”

Rebuttal

Brinckerhoff, responding to Bansal’s hypothetical about how the presence of some public use trumps private benefit, asserted, “There’s no question that Kelo prohibits that fact pattern.”

As for the record, “there is no record in this case,” he said. (Well, there’s an ESDC record.)

Korman, trying to characterize Brinckerhoff’s argument, said, “you conclude we should reverse so the public will know the manner in which this project was developed.”

He added, “Is this lawsuit a pretext?”

Brinckerhoff said it was so “my clients can know, when their homes are taken,” that it’s legitimate. Given all the indicia that it’s not legitimate, he said, the case should go forward. (He left out how some simply oppose Atlantic Yards.)

Katzmann asked about ongoing state cases. Brinckerhoff cited one case involving renters challenging the state’s relocation offer but didn’t mention the challenge to the environmental review.

Could the plaintiffs have raised the claims in state court, Korman asked. No, said Brinckerhoff, indicating that they could only sue the ESDC.

And that was it; even though there were more cases on the docket, most of the crowd left the courtroom.

Recusal redux

Afterward, a cluster of reporters asked their questions, with Forest City Ratner spokesman Loren Riegelhaupt leaning in.

After a while, I asked Brinckerhoff why he didn’t ask Korman to recuse himself.

Brinckerhoff paused.

Korman, Brinckerhoff said, was unclear about what exactly he’d done. “I know Judge Korman," he said. "I think he has tremendous integrity.”

Brinckerhoff acknowledged that, while it’s “foolish” to predict a judge’s vote by the questions asked at argument, Korman’s questions “were not necessarily” the ones he would’ve wanted.

Speculation on Korman

So, why would Korman have sent back a “yes” to a Ratner flier? We don’t know, and we don’t know his current knowledge or opinion of the project.

But perhaps the initial plans sounded good, as they did, to a lot of people. Korman went to school in Flatbush while the Dodgers were playing; he was about 15 when the team left Brooklyn in 1957. In other words, he's a contemporary of Borough President Marty Markowitz, who wanted to bring basketball to Brooklyn and got a whole lot more.

The plaintiffs—*13 residential and commercial tenants and property owners—are challenging U.S. District Judge Nicholas Garaufis’s dismissal of the case, as he ruled that the public purposes associated with the project—among them subsidized housing, blight removal, new transit facilities, and a sports facility—trumped any inquiry into the legitimacy of the sequence.

[Update: *To clarify: there were 13 original plaintiffs. Two have been said to drop out but have not done so additionally. One additional plaintiff has been added when a separate suit was consolidated. So there are currently 14, and likely 12.]

Then again, they gave plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff (right) a lot of time to explain his argument that the sequence behind Atlantic Yards—in which the project was promised to a private developer without any other bids—differed from that in the cases the Supreme Court had upheld eminent domain, and that Garaufis's ruling should be reversed so the case can actually go forward.

Then again, they gave plaintiffs’ attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff (right) a lot of time to explain his argument that the sequence behind Atlantic Yards—in which the project was promised to a private developer without any other bids—differed from that in the cases the Supreme Court had upheld eminent domain, and that Garaufis's ruling should be reversed so the case can actually go forward.(The Supreme Court’s 2005 Kelo v. New London decision upheld eminent domain because the city “carefully formulated a development plan.” and Justice Anthony Kennedy’s non-binding concurrence gave specific examples, including “evidence that respondents reviewed a variety of development plans and chose a private developer from a group of applicants rather than picking out a particular transferee beforehand,” not present in the Brooklyn case.)

Later, when he answered questions outside the courtroom Brinckerhoff brought up the obvious comparison: the ongoing bid process for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Hudson Yards, in which several developers are competing.

And while the judges did not press attorney Preeta Bansal (right), representing the Empire State Development Corporation and other defendants, as closely as they did Brinckerhoff, they did question her somewhat startling contention that, even if there were illicit motive in the case, as long as the project results in some public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” (The other defendants include Mayor Mike Bloomberg, former Gov. George Pataki, and Forest City Ratner.)

And while the judges did not press attorney Preeta Bansal (right), representing the Empire State Development Corporation and other defendants, as closely as they did Brinckerhoff, they did question her somewhat startling contention that, even if there were illicit motive in the case, as long as the project results in some public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” (The other defendants include Mayor Mike Bloomberg, former Gov. George Pataki, and Forest City Ratner.)(Here's the Times's blog coverage and print coverage. Here's the Observer, the Sun, AM NY, AP, and NY 1.)

A non-recusal

As the day’s proceedings began, and before the two oral arguments that proceeded Goldstein v. Pataki, Judge Edward Korman, a district judge sitting on the appellate court, announced that he had received an Atlantic Yards mailer “some years ago” and responded in the affirmative. (It’s not clear what mailing he got, but it could have been this May 2004 flier. Click to enlarge.)

As the day’s proceedings began, and before the two oral arguments that proceeded Goldstein v. Pataki, Judge Edward Korman, a district judge sitting on the appellate court, announced that he had received an Atlantic Yards mailer “some years ago” and responded in the affirmative. (It’s not clear what mailing he got, but it could have been this May 2004 flier. Click to enlarge.)The plaintiffs made no move to ask Korman, a distinguished jurist, to recuse himself, but as the argument wore on and Korman asked some tough questions, they might have had second thoughts.

Leading off

Brinckerhoff didn’t get far before he was interrupted by Judge Robert A. Katzmann, who suggested that Atlantic Yards would include “classic cases of direct public use,” cited in Kelo, “that would foreclose much of your argument.”

Brinckerhoff responded that, in this case, the blight determination was made years after the decision to have Forest City Ratner develop this project.

Korman asked if there was “any dispute” that 62% of the project site was blighted, the land from the north side of Pacific Street that encompasses the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA. (It established in 1968 during very different times, but reaffirmed ten times, most recently in 2004.)

Korman asked if there was “any dispute” that 62% of the project site was blighted, the land from the north side of Pacific Street that encompasses the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, or ATURA. (It established in 1968 during very different times, but reaffirmed ten times, most recently in 2004.)Brinckerhoff pointed out that his clients’ properties are all outside ATURA.

[They’re on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street. In the map, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.]

“Does that matter?” Katzmann asked. “Does there have to be a lot-by-lot determination?”

Brinckerhoff said no, as long as the sequence was legitimate. In the Supreme Court's Berman v. Parker case, he pointed out, the circumstances were “radically different,” as a legislative finding that the area was in need of renewal was followed by a request for proposals.

He said that in this case, there was no legislative determination, citing the role of the ESDC, an “unelected body.”

Korman cut him off, asking how this affected the question of public use or public purpose.

“It lessens the deference owed to decision makers,” Brinckerhoff replied.

Korman asked how the ESDC differed from other administrative agencies to which elected officials delegate certain powers.

Brinckerhoff pointed to a case involving Amtrak in which a court said a lesser amount of deference was warranted.

“The sequence gives a powerful inference,” he said, “that the taking was motivated to benefit a specific developer.” Forest City Ratner was the only developer considered, he said, and the “post-hoc” blight study concerned only the footprint that Forest City Ratner had identified.

Private motive?

“If there are public uses to be had, what different does it make that an individual has a private, self-interested motive?” Katzmann asked.

Brinckerhoff responded with a hypothetical, a government use of eminent domain for a public park, in which most of the site actually benefited the private developer.

The circumstances, he said, were like Aaron v. Target Corp., a Missouri case in which officials from Target told a city official they’d abandon the store unless they got new property through eminent domain; Target was designated as the city’s “chosen redeveloper only days after soliciting alternatives from the public.”

Korman was skeptical. “In your hypothetical, the other use has nothing to do with the park. In this instance, the property taken is directly related to the property as a whole.” He asked if Brinckerhoff would question a case in which the city took the Atlantic Yards site for its own use.

Brinckerhoff agreed that, if a government entity had followed proper procedures, it would be OK.

“The city’s purpose,” Korman pressed on, “is to derive all the benefits. They have concluded, for whatever reason, these defendants are the best suited to carry it out. Does that taint the process?”

Brinckerhoff pointed to a recent case, with “not as compelling” facts, in which a court refused to dismiss a case in which the sole allegation was that the decision to take property was made after the developer was chosen.

Why would that affect the outcome, Korman asked.

The government, Brinckerhoff said, should maximize its benefits.

Katzmann asked whether a New York case called Brody v. Port Chester dealt with the procedural issues.

Brinckerhoff agreed that the procedures in this case were consistent with the state’s eminent domain law. However, he suggested there was far greater transparency in the Kelo case, which involved a seven-day bench trial.

Corruption question

Katzmann asked if there was any specific relationship between the developer and public officials.

Brinckerhoff noted that former Gov. George Pataki, a defendant, went to law school with Bruce Ratner, that Ratner was known as a past contributor to Pataki, and there were reports that they were friends.

(A 12/10/03 Ratner profile in the New York Sun stated: Since 1986, the registered Democrat has donated almost $30,000 to local politicians, and since 2000, companies he controlled donated $7,500 to state groups affiliated with Governor Pataki.)

Beyond that, he said, there was no need for evidence of a quid pro quo, just the circumstances. In Target, he said, “the motive was that [the officials] wanted to keep Target in the community,” but Target selected the property and the government followed its lead.

How much discovery?

The plaintiffs’ goals are merely to proceed with discovery, to gain pre-trial information through documents, depositions, and interrogatories

Katzmann asked how much discovery the plaintiffs sought. Brinckerhoff was cautious, as if not wanting to suggest a fishing expedition. “Presumably rather limited,” he said.

Katzmann asked what the plaintiffs want to find out.

“To explain these anomalies” regarding the sequence, Brinckerhoff said. He suggested “some limited depositions,” noting that there’s already a limit of seven according to the federal rules.

Korman asked Brinckerhoff what, in the best case scenario, he wished to find.

“There’s every possibility,” Brinckerhoff responded, that there are documents “that make it clear the government was uninterested” in other developers and projects, and that the governor and mayor had relationships with Bruce Ratner that led them to favor him."

Korman asked what was wrong with the officials thinking that Ratner’s done good work and would do a good job on this project. (Brinckerhoff responded, but my notes are fuzzy.)

The city's motive

(As for the city's motive, part of it was answered by Andrew Alper, then president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, who testified at a 5/4/04 City Council hearing:

This particular project came to us. We were not out soliciting, we were developing a Downtown Brooklyn Plan, but we were not out soliciting a professional sports franchise for Downtown Brooklyn.

The developer came to us with what we thought was actually a very clever plan. It is not only bringing a sports team back to Brooklyn, but to do it in a way that provided dramatic economic development catalyst in terms of housing, retail, commercial jobs, construction jobs, permanent jobs.

So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and find to try to a better deal. I think that would discourage developers from coming to us, if every time they came to us we went out and tried to shop their idea to somebody else. So we are actively shopping, but not for another sports arena franchise for Brooklyn.)

Sports facility public?

Brinckerhoff soon got his steam back, arguing that “the notion that a stadium is a public use is just wrong.” (Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in her Kelo dissent identified a stadium as a public use, but without any citations.) “A stadium is a private, money-making enterprise,” he said, not different from a hotel that offers public access.

Korman brought up the example of Yankee Stadium, where municipal officials, “rightly or wrongly,” believe “there’s a significant benefit” to having a baseball team. He noted that the city would condemn property for a new Metro North station to serve the Yankees.

Brinckerhoff said it depended on the process, but noted “it’s widely understood that stadiums are money-losing enterprises.”

Courts step in?

“Is that something a court should ascertain?” Katzmann asked, nothing that certain issues are reserved for the political process.

Brinckerhoff said the case involved many claims, not just one.

Katzmann acknowledged that courts might want to say something “about the wisdom of a policy, but we’re constrained.”

Brinckerhoff reminded him that courts play a role in policing eminent domain when it seems to be motivated to benefit a specific private individual. “There’s no explanation,” he said, for why the MTA, shortly after the project was announced, said that the property was going to go to Forest City Ratner, before later issuing an RFP.

Korman wondered whether the plaintiffs would object to the exact same project if it has resulted from a more fair process, bidding in response to an RFP.

Had a government entity, Brinckerhoff said, decided through a legitimate process that the project was in the public interest, including before the private beneficiary was known, it could be acceptable. (It wasn't clear if he was acknowledging weakness in the plaintiffs’ argument that the public benefit, in terms of actual affordable housing, new tax revenues, etc., would be far lower than the government claims.)

“We have this area in Downtown Brooklyn,” Korman said, making the common error of not locating the project in Prospect Heights. “Somebody submits a proposal similar to Ratner. It goes through the hoops…” What if it benefits a private party?

“That in itself is not a problem,” Brinckerhoff responded. “It’s when the private party has driven the process.”

But what about a mixed motive, Korman asked, to benefit the public and the developer? (That's a reading of the Alper testimony.)

The previous cases, Brinckerhoff responded, differ significantly in the sequence: “All we’re asking for is that this case can be remanded so the public can know this particular decision was legitimate.”

Defense case

Bansal, arguing for the defense, declared “the analysis of this matter begins and ends with Kelo,” contending that the “multiple public purposes” made it an open and shut case.

What about the “post-hoc” blight study to which Brinckerhoff alluded, asked Katzmann.

Bansal focused on the ATURA designation, renewed in 2004. “It’s undisputed that the project would alleviate blight” in 63% of the site. “That is enough to basically end the case,” she said.

Citing the benefits, she noted that it would “create a publicly-owned sports arena.”

Publicly-owned?, asked Katzmann.

“And then leased” to a private entity, Bansal acknowledged.

“And then leased” to a private entity, Bansal acknowledged.Several people in the crowd snickered, knowing that the lease would be for $1. (See the 2/18/05 Memorandum of Understanding between the city, state, and developer.)

She cited the planned Urban Room, “a nice entrance to the subway” and transit improvements “that Brooklyn has been trying to do for decades.” The MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard was “in desperate need of modernization.” (Still, there’s been no testimony that the MTA or “Brooklyn” had either of these on a publicly announced wish list.)

The seven acres of public space (actually, eight), she said, will connect neighborhoods that are separated. (BrooklynSpeaks disagrees.)

“What if the process is tainted?” Katzmann asked.

The constitutional analysis, Bansal said, does not depend on the sequence.

“It’s not just the sequence,” Korman continued, saying Brinckerhoff “relies on all these shortcuts,” including “evidence of a preconceived plan.”

Illicit motive OK

Bansal then gave a hypothetical worst-case scenario in which a smoking-gun memo or video showed that a public official stated, “I want to do this for Bruce Ratner.”

It would not make a difference. “The fact that there might be illicit motive,” she said, even if it’s the principal motive, if it results in public use, “that’s the end of the inquiry.” She said the issue was whether public officials could have rationally concluded there was some public purpose.

(It was reminiscent of her colleague Douglas Kraus's comment at a hearing in February that if Brinckerhoff's "clients or if other members of the community think this was really a terrible project, they can express themselves in the next election.")

Katzmann tried to drill down to an inflection point. What if an area was 20% blighted, or 50%, or 80%--how much blight would be needed to assume that decision makers acted rationally?

There’s no clear line of demarcation, Bansal said, suggesting the court’s inquiry would be “fact-specific. But we’re not close,” given the ATURA finding. “I don’t think this case is anywhere near the line.”

Judge Debra Ann Livingston, who had asked only a few questions, also pressed toward the inflection point. A court faced with procedural irregularities, she said, and just one acre of public space, would look further.

Bansal pointed to Kennedy’s Kelo concurrence, arguing that, while certain kinds of cases based on eminent domain for economic development cases may suggest pretext, there’s “nothing close to that here, given the multiple public purposes.” (The plaintiffs argue that Kelo speaks to cases beyond economic development.)

Developer-driven projects OK?

With respect to the sequence, she added, the “New York legislature has made a considered judgment that private enterprise-initiated projects… are to be favored.”

(Actually, when the Urban Development Corporation was established in 1968 the effort to encourage "maximum" private participation in project was hardly focused on developments like Atlantic Yards, but instead intended to get the private sector to finally invest in the low- and middle-income subsidized housing.)

Few developers can do these kinds of projects, she added, somehow missing the Hudson Yards example. “The fact that a private developer came to the city is of no constitutional moment.”

“Your adversary,” Katzmann said, suggested that other developers could have done it for less money, and were not considered.

That, Bansal declared, was not a federal issue. “Perhaps they have a claim under state law.”

Rebuttal

Brinckerhoff, responding to Bansal’s hypothetical about how the presence of some public use trumps private benefit, asserted, “There’s no question that Kelo prohibits that fact pattern.”

As for the record, “there is no record in this case,” he said. (Well, there’s an ESDC record.)

Korman, trying to characterize Brinckerhoff’s argument, said, “you conclude we should reverse so the public will know the manner in which this project was developed.”

He added, “Is this lawsuit a pretext?”

Brinckerhoff said it was so “my clients can know, when their homes are taken,” that it’s legitimate. Given all the indicia that it’s not legitimate, he said, the case should go forward. (He left out how some simply oppose Atlantic Yards.)

Katzmann asked about ongoing state cases. Brinckerhoff cited one case involving renters challenging the state’s relocation offer but didn’t mention the challenge to the environmental review.

Could the plaintiffs have raised the claims in state court, Korman asked. No, said Brinckerhoff, indicating that they could only sue the ESDC.

And that was it; even though there were more cases on the docket, most of the crowd left the courtroom.

Recusal redux

Afterward, a cluster of reporters asked their questions, with Forest City Ratner spokesman Loren Riegelhaupt leaning in.

After a while, I asked Brinckerhoff why he didn’t ask Korman to recuse himself.

Brinckerhoff paused.

Korman, Brinckerhoff said, was unclear about what exactly he’d done. “I know Judge Korman," he said. "I think he has tremendous integrity.”

Brinckerhoff acknowledged that, while it’s “foolish” to predict a judge’s vote by the questions asked at argument, Korman’s questions “were not necessarily” the ones he would’ve wanted.

Speculation on Korman

So, why would Korman have sent back a “yes” to a Ratner flier? We don’t know, and we don’t know his current knowledge or opinion of the project.

But perhaps the initial plans sounded good, as they did, to a lot of people. Korman went to school in Flatbush while the Dodgers were playing; he was about 15 when the team left Brooklyn in 1957. In other words, he's a contemporary of Borough President Marty Markowitz, who wanted to bring basketball to Brooklyn and got a whole lot more.

Comments

Post a Comment