Did the Atlantic Yards affordable housing information session last night backfire on developer Forest City Ratner and its partner, housing advocacy group ACORN?

Did the Atlantic Yards affordable housing information session last night backfire on developer Forest City Ratner and its partner, housing advocacy group ACORN?Not completely. After all, FCR collected contact and demographic information (household income, type of employment, current housing payment) from the attendees, a good cross-section of average community folk in Brooklyn and beyond.

More than 2000 people (the Times said 2300) attended the 6:30 pm session, filling the room, so FCR scheduled a second session, at 8:15 pm, which drew a much smaller crowd to a large room. (So, what happened to those 5000 RSVPs?)

A photographer worked the first session, so photos of the crowd likely will appear on the AtlanticYards.com web site and perhaps in a future issue of the developer's promotional Brooklyn Standard.

However, if project planners were looking to generate significant new support, as opponents plan a protest and the state environmental review hits its stride, they might try another tactic.

The applause for the project was tepid; the strongest reaction came when people questioned the housing's cost and timetable. A large portion of the crowd walked out after 40 minutes, before the 20-minute Q & A.

Why? Perhaps because they had already learned some key facts: applications wouldn’t be available for at least three years, with occupancy a year later, and two-thirds of the places in the lottery will have preferences.

The Daily News, in an article today headlined B'klyn Yards pitch finds few bargains, found attendees ranging from angry to cautiously optimistic. "First they told us apartments might be ready by 2009, but then there's the lottery thing," one said.

The Times characterized the crowd as "attentive" in an article headlined Promises of Atlantic Yards Draw Thousands to Meeting. Unlike the Daily News and the Sun articles, the Times didn't quote critics expressing skepticism about the session, but the article did observe:

But last night’s presentations served as an early test of local interest in Forest City’s plans, and the audience members, many of them from Brooklyn neighborhoods that have seen promises of housing and jobs go unfulfilled before, listened with high hopes and some wariness.

The New York Sun, in an article today headlined Queue Forms For Housing In Brooklyn, quoted City Council Member Letitia James as saying that only 20% of the affordable Atlantic Yards units would truly be affordable. (Of the 2250 units, 900 would go to low-income people, earning under $35,450 for a family of four.) The article also pointed out that the session was timed to coincide with the state's pending release of the draft environmental impact statement, which would commence a public comment period. A final environmental review and state approvals are still required, but probable lawsuits aimed at the developer's likely use of eminent domain could delay or even derail the project.

The New York Observer reported that many in the largely black crowd "were disappointed to find that 'affordable housing' was not that affordable, or accessible."

The New York Post offered two paragraphs.

I got in, somewhat to my surprise. On Monday morning, I wrote that I hadn’t received a response to my RSVP, even though I had responded quickly after I received an email the Wednesday before.

On Monday afternoon, I received an automated phone call confirming my registration. (Technical delay or response to my article? I don't know.) When I and hundreds of others arrived at the Marriott Hotel in Downtown Brooklyn last night, no one was checking names; it would’ve been too unwieldy.

Stuckey opens

Jim Stuckey, president of the Atlantic Yards Development Group, opened by citing the response to the brochure mailed to 600,000 Brooklynites.

Jim Stuckey, president of the Atlantic Yards Development Group, opened by citing the response to the brochure mailed to 600,000 Brooklynites.“We were very surprised that we got back 20,000 cards asking about affordable housing,” he declared. Surprised? As Lumi Rolley of NoLandGrab observed, the only offer on the return card was a check box stating, "YES! Please let me know when housing applications are available." It would stand to reason that a majority of respondents who want the inside track on housing applications are interested in "affordable housing."

Marty, man of the people

Borough President Marty Markowitz took the mike, declaring that “this is an exciting time to live in Brooklyn,” but, regarding new developments, “Sadly, almost all are beyond our reach—yours and mine.” (Note: Marty earns $135,000, and eats a lot of free meals.)

Markowitz recalled his own humble origins in rent-controlled and then public housing, which launched his political career as a tenant advocate . “I’m a tenant,” he added, “and I pay more than 50 percent of my take-home income in rent.” (Emphasis added.) The guidelines for affordable housing at the Atlantic Yards project use 30 percent of a family's income, but that's pre-tax income, the standard calculation.

Markowitz said he knew the project had some detractors, “but no one in America and New York City is setting the standards—only Forest City Ratner is doing that.”

(What about the inclusionary zoning in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, which was negotiated publicly by City Council, rather than the privately deal announced by FCR and ACORN? The Atlantic Yards project would have a significant percentage of affordable housing, but not the 50 percent originally promised, and the inclusion of affordable housing has been used to argue for a project out of scale with most of the surrounding neighborhood.)

“A beautiful new apartment for each and every one of you—that’s my wish,” he said, signing off. Given that 20,000 people expressed an interest in 2250 projected units, Markowitz's wish can't be fulfilled by this project.

Project overview

Stuckey then gave an overview of the project: 4500 rental apartments, half-affordable, half market; 2360 condos, 7 acres of open space, an “arena for the New Jersey Nets, who will become the Brooklyn Nets.” At that, there were a few claps. People care much less about hoops than about housing. (And would they stay the Nets? A name change has been contemplated.)

A slide promised “Quality Residential Buildings,” citing:

--“high-quality construction using union labor”

--“world class architecture by Frank Gehry”

--“well-designed and efficient living spaces”

--“24-hour doormen and lobby attendants for service and security”

--“building amenities for residents such as children’s playroom, laundry rooms, bike storage, fitness center.”

He also mentioned that the project would include a health clinic, so people who need blood tests or MRIs wouldn’t have to travel far.

Stuckey explained how this program actually is an improvement over many current affordable housing programs. About half of the affordable units [update: actually, in square footage] will be two- and three-bedroom units, thus accommodating families. “We’re talking about teachers, bus drivers, cops, civil servants,” he said.

All the units would be rent-stabilized, with increases set by the Rent Stabilization Board, he said. That raises a question. Units that rent for $2000 a month exit the rent stabilization program, and perhaps 30 percent of the units would rent for $2000 or more. (Everyone would pay 30 percent of their income in rent, so anyone earning $80,000 would pay $24,000 a year, or $2000 a month, in rent.)

While apartments can remain rent-stabilized when they rise above $2000, it's not clear that the program accommodates units starting at that figure. [Update: it does.]

What about the promised affordable, for-sale condos, 600 to 1000, which could be built onsite or off-site? “We will be working on putting [it] together,” Stuckey said, his words suggesting it's hardly soon.

Lewis enters

ACORN head Bertha Lewis offered some background on the city’s housing challenge: a microscopic housing vacancy rate, 79,000 people living doubled up, 240,000 people on the waiting list for public housing, and the steady decrease in all forms of subsidized housing in the city. “We know this is a crisis.”

“When we started to talk about it, there was a principle,” she said. Every building would be mixed affordable housing and market-rate housing. “If the elevator works for them, the elevator’s gotta work for you,” she said, to some healthy applause, probably the high point of the night for project proponents. It’s a worthy point; many other affordable housing programs are relegated to separate buildings or other neighborhoods.

She also pointed out that few affordable housing programs help middle-income families, say when one person earns $30,000 and a spouse earns $50,000: “There’s no program for them.”

AMI vs. local income

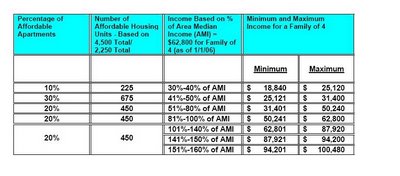

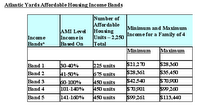

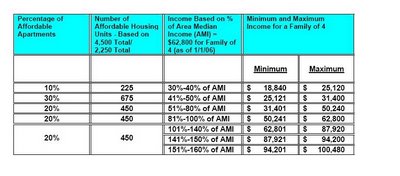

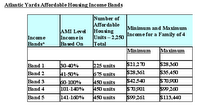

Note that the income levels have gone up since the project was first announced (graphic at right), though the income bands—the ranges—are the same.

Note that the income levels have gone up since the project was first announced (graphic at right), though the income bands—the ranges—are the same.

Band 1 is for people with 30-40% of the federally-calculated Area Median Income (AMI), while Band 5 is 141-160%. The AMI, formerly $62,800, has gone up to $70,900 since April 7.

The slide show gave five examples, one for each of the five bands, with an ethnically-diverse mix of four-person families, each including two children:

The slide show gave five examples, one for each of the five bands, with an ethnically-diverse mix of four-person families, each including two children:

--Mr. Robbins, a plumber, and his retired wife raising their two grandchildren. Their $24,815 annual income would lead to a $620 monthly rent.

--Mr. Martinez, a transit worker, and his homemaker wife. Their annual income of $31,905 would lead to a $797 rent.

--Mrs. Lim, an administrative assistant, and her husband, unable to work, raising two children. Her annual income of $56,720 would mean a $1418 rent.

--Mr. and Mrs. James, teachers earning $85,080, paying $2127 in rent.

--Mr. Patel, an accountant, and Mrs. Patel, a home health-care worker, earning $106,705, and paying $2658 a month.

Again, Lewis cited the importance of affordable housing for the middle-class. She had a point, but some in the crowd didn't welcome it.

Then again, Lewis pushed the envelope, claiming of the middle-class, “These people--they’re paying a minimum of $2500 up to $4000.” Not so. A quick web search shows a good number of two-bedroom apartments in neighborhoods reasonably close to the project site—admittedly, not new Frank Gehry buildings—for under $2500.

Preferences and timeline

There is a housing lottery, but the preferences announced, required by city regulations, deflated some people in the room. Half the affordable units—1125 of 2250—would be reserved for residents of the three Community Boards, CBs 2, 6, & 8.

Five percent would go to police officers and another five percent to city employees. Five percent would go to the mobility-impaired and one percent each to the sight- and hearing-impaired. That’s two-thirds of the units, plus ten percent for seniors, though there could be some overlap.

Stuckey offered a timeline. Assuming approvals, the railyard would have to be moved first, and then the construction of the first residential buildings would begin in 2008. Marketing for the buildings would begin in 2009, with applications available.

Occupancy would occur in mid-2010, and the final buildings would be completed in 2016. He didn’t mention that there could be delays, that the Nets have discussed extending their lease for another three years.

Q&A

The Question and Answer session began, and the crowd begin streaming out. A questioner who identified herself as a teacher commented that the two-bedroom apartments “seem somewhat unaffordable.” Lewis reminded her that the rent is 30 percent of income, which is the national standard for affordable housing.

Another questioner, from the Bronx, asked if she could use her Section 8 voucher at the Atlantic Yards project. Lewis responded, “If you have a voucher and it travels with you, it’s going to travel with you.”

The next questioner apologized for complaining, “but where is the stabilization if the two bedroom apartment over $2000?” Several in the audience clapped. “Why is it only in Brooklyn, when we’ve got five boroughs waiting for the same thing?”

Stuckey patiently pointed out that a rent costing 30 percent of income was the standard, and noted that the project must follow city guidelines for the lottery.

Another questioner challenged the way AMI was calculated. “We get paid after taxes,” the woman said, saying that after taxes, paying for a babysitter, groceries, and other things, costs added up. Again, people clapped.

“I hear you,” Lewis responded, again citing the rules and reminding people that most affordable housing programs go up to only one bedroom.

More on subsidies

So who's to blame? Not developers that put up luxury buildings with tax breaks.

Lewis blamed the government: “If the government, the city and the state and the feds really wanted to make things affordable for real, we would need more subsidy. The government, which we are fighting every single day.”

Well, not quite. Lewis got nice and chummy with Mayor Mike Bloomberg when the Housing Memorandum of Understanding was signed last year. Click through for that "Sealed with a kiss" photo by Tom Callan.

“If they can fund wars, they can fund affordable housing,” she declared. But she didn’t mention reform of 421-a, the subsidy for market-rate housing that ACORN has criticized.

Another questioner asked about the for-sale units. Stuckey said it was a question of taxpayer subsidies. “We are getting a tremendous amount of support from the city and the state,” he said, noting that FCR is looking at whether such units could be built onsite or offsite. (Prediction: they wouldn't dare add to an already overly dense project.)

Lewis added, “You need to have the subsidies to do that.”

Unanswered was how much government funding would go to affordable housing for this project, and why exactly it has to go here rather than elsewhere.

More skepticism

Another questioner pointed out that there is a crisis right now, and asked whether the affordable housing would be built offsite.

Lewis said the rentals would be built onsite. “I’m not going to blow smoke,” she said. “The project hasn’t been fully approved.” Or halfway approved, actually, given that a Draft Environmental Impact Statement has yet to appear from the Empire State Development Corporation.

“There’s 96 projects going on in Brooklyn right now,” she added. “Not a scrap of it is affordable.” Not quite. ACORN’s report, Sweetheart Development issued in March, said that only 7 percent of the units in 87 new developments in and around Downtown Brooklyn include affordable housing, though city officials disputed that.

People still had their hands up, but it was 7:30, so the session came to a close. Audience members handed in their information surveys and picked up photocopies of the PowerPoint presentation, which would remind them of their chances in the lottery, and the developer's timeline for a project that, indeed, has not been fully approved.

What about the promised affordable, for-sale condos, 600 to 1000, which could be built onsite or off-site? “We will be working on putting [it] together,” Stuckey said, his words suggesting it's hardly soon.

Lewis enters

ACORN head Bertha Lewis offered some background on the city’s housing challenge: a microscopic housing vacancy rate, 79,000 people living doubled up, 240,000 people on the waiting list for public housing, and the steady decrease in all forms of subsidized housing in the city. “We know this is a crisis.”

“When we started to talk about it, there was a principle,” she said. Every building would be mixed affordable housing and market-rate housing. “If the elevator works for them, the elevator’s gotta work for you,” she said, to some healthy applause, probably the high point of the night for project proponents. It’s a worthy point; many other affordable housing programs are relegated to separate buildings or other neighborhoods.

She also pointed out that few affordable housing programs help middle-income families, say when one person earns $30,000 and a spouse earns $50,000: “There’s no program for them.”

AMI vs. local income

Note that the income levels have gone up since the project was first announced (graphic at right), though the income bands—the ranges—are the same.

Note that the income levels have gone up since the project was first announced (graphic at right), though the income bands—the ranges—are the same.Band 1 is for people with 30-40% of the federally-calculated Area Median Income (AMI), while Band 5 is 141-160%. The AMI, formerly $62,800, has gone up to $70,900 since April 7.

The slide show gave five examples, one for each of the five bands, with an ethnically-diverse mix of four-person families, each including two children:

The slide show gave five examples, one for each of the five bands, with an ethnically-diverse mix of four-person families, each including two children:--Mr. Robbins, a plumber, and his retired wife raising their two grandchildren. Their $24,815 annual income would lead to a $620 monthly rent.

--Mr. Martinez, a transit worker, and his homemaker wife. Their annual income of $31,905 would lead to a $797 rent.

--Mrs. Lim, an administrative assistant, and her husband, unable to work, raising two children. Her annual income of $56,720 would mean a $1418 rent.

--Mr. and Mrs. James, teachers earning $85,080, paying $2127 in rent.

--Mr. Patel, an accountant, and Mrs. Patel, a home health-care worker, earning $106,705, and paying $2658 a month.

Again, Lewis cited the importance of affordable housing for the middle-class. She had a point, but some in the crowd didn't welcome it.

Then again, Lewis pushed the envelope, claiming of the middle-class, “These people--they’re paying a minimum of $2500 up to $4000.” Not so. A quick web search shows a good number of two-bedroom apartments in neighborhoods reasonably close to the project site—admittedly, not new Frank Gehry buildings—for under $2500.

Preferences and timeline

There is a housing lottery, but the preferences announced, required by city regulations, deflated some people in the room. Half the affordable units—1125 of 2250—would be reserved for residents of the three Community Boards, CBs 2, 6, & 8.

Five percent would go to police officers and another five percent to city employees. Five percent would go to the mobility-impaired and one percent each to the sight- and hearing-impaired. That’s two-thirds of the units, plus ten percent for seniors, though there could be some overlap.

Stuckey offered a timeline. Assuming approvals, the railyard would have to be moved first, and then the construction of the first residential buildings would begin in 2008. Marketing for the buildings would begin in 2009, with applications available.

Occupancy would occur in mid-2010, and the final buildings would be completed in 2016. He didn’t mention that there could be delays, that the Nets have discussed extending their lease for another three years.

Q&A

The Question and Answer session began, and the crowd begin streaming out. A questioner who identified herself as a teacher commented that the two-bedroom apartments “seem somewhat unaffordable.” Lewis reminded her that the rent is 30 percent of income, which is the national standard for affordable housing.

Another questioner, from the Bronx, asked if she could use her Section 8 voucher at the Atlantic Yards project. Lewis responded, “If you have a voucher and it travels with you, it’s going to travel with you.”

The next questioner apologized for complaining, “but where is the stabilization if the two bedroom apartment over $2000?” Several in the audience clapped. “Why is it only in Brooklyn, when we’ve got five boroughs waiting for the same thing?”

Stuckey patiently pointed out that a rent costing 30 percent of income was the standard, and noted that the project must follow city guidelines for the lottery.

Another questioner challenged the way AMI was calculated. “We get paid after taxes,” the woman said, saying that after taxes, paying for a babysitter, groceries, and other things, costs added up. Again, people clapped.

“I hear you,” Lewis responded, again citing the rules and reminding people that most affordable housing programs go up to only one bedroom.

More on subsidies

So who's to blame? Not developers that put up luxury buildings with tax breaks.

Lewis blamed the government: “If the government, the city and the state and the feds really wanted to make things affordable for real, we would need more subsidy. The government, which we are fighting every single day.”

Well, not quite. Lewis got nice and chummy with Mayor Mike Bloomberg when the Housing Memorandum of Understanding was signed last year. Click through for that "Sealed with a kiss" photo by Tom Callan.

“If they can fund wars, they can fund affordable housing,” she declared. But she didn’t mention reform of 421-a, the subsidy for market-rate housing that ACORN has criticized.

Another questioner asked about the for-sale units. Stuckey said it was a question of taxpayer subsidies. “We are getting a tremendous amount of support from the city and the state,” he said, noting that FCR is looking at whether such units could be built onsite or offsite. (Prediction: they wouldn't dare add to an already overly dense project.)

Lewis added, “You need to have the subsidies to do that.”

Unanswered was how much government funding would go to affordable housing for this project, and why exactly it has to go here rather than elsewhere.

More skepticism

Another questioner pointed out that there is a crisis right now, and asked whether the affordable housing would be built offsite.

Lewis said the rentals would be built onsite. “I’m not going to blow smoke,” she said. “The project hasn’t been fully approved.” Or halfway approved, actually, given that a Draft Environmental Impact Statement has yet to appear from the Empire State Development Corporation.

“There’s 96 projects going on in Brooklyn right now,” she added. “Not a scrap of it is affordable.” Not quite. ACORN’s report, Sweetheart Development issued in March, said that only 7 percent of the units in 87 new developments in and around Downtown Brooklyn include affordable housing, though city officials disputed that.

People still had their hands up, but it was 7:30, so the session came to a close. Audience members handed in their information surveys and picked up photocopies of the PowerPoint presentation, which would remind them of their chances in the lottery, and the developer's timeline for a project that, indeed, has not been fully approved.

Comments

Post a Comment